On Thursday 7 September, Channel Four broadcast a fascinating programme as part of its series Secret History, entitled Mutiny - the true story of Red October. This remarkable documentary for the first time gave us the true story behind the 1990 Hollywood movie The Hunt for Red October a film version of a 1984 novel by Tom Clancy.

"Trust the fact that history will judge events honestly and you will never have to be embarrassed for what your father did. On no account ever be one of those people who criticise but do not follow through their actions. Such people are hypocrites - weak, worthless people who do not have the power to reconcile their beliefs with their actions. I wish you courage, my dear. Be strong in the belief that life is wonderful. Be positive and believe that the Revolution will always win."

(Valery Sablin's last letter to his son before his execution)

Clancy's story of Marko Ramius, a defecting submarine captain who takes his ship on an epic voyage across the Atlantic, was inspired by real events.

The author took as his starting point a mutiny led by Valery Sablin on the Soviet warship the Sentry (Storozhevoy, in Russian) in November 1975. As he explains in his book, 'There is a precedent for this, sir. On November 8, 1975, the Storozhevoy, a Soviet Krivak-class missile frigate, attempted to run from Riga, Latvia, to the Swedish island of Gotland. The political officer aboard, Valery Sablin, led a mutiny of the enlisted personnel. Sablin and 26 others were court-martialled and shot.' However, the real story of the Red October was hidden at the time by the Soviet government and only now have been revealed.

Until the end of the Cold War western intelligence believed that the crew was going to defect, and this was the basis of Clancy's book and the film. However, new evidence which emerged during the last days of the Soviet Union and which was revealed in the Channel Four programme shows that Clancy's account is inaccurate. The aim of the Sentry was not to defect to the West, nor could it be because the leader of the mutiny, Valery Sablin was a committed Communist. His intention was not to flee to the West, but to provoke a political revolution in the USSR with the aim of overthrowing the rule of the privileged Stalinist bureaucracy and restoring a genuine regime of Leninist soviet democracy. As the programme's notes put it: "A fervent believer in Communism, Sablin was making for Leningrad (now St Petersburg). Inspired by the memory of the battleship Potemkin, which had mutinied during the rising of 1905, and by the cruiser Aurora, which had ignited the revolution of 1917, he hoped that his mutiny would spark a new rebellion in Leningrad, and complete what he saw as the unfinished Russian Revolution."

This is a true-life story that is richer, more extraordinary and more moving than even the finest works of fiction. It will undoubtedly inspire the workers and youth of Russia and the entire world. This marvellous documentary deserves the widest possible audience.

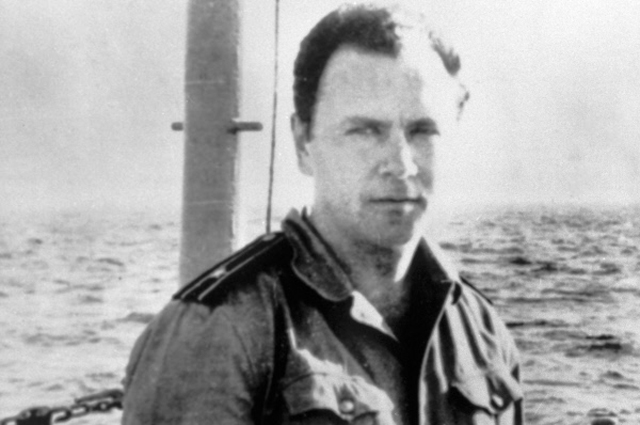

Who was Valery Sablin?

Valery Mikhailovich Sablin was the son and grandson of naval officers, and followed in their footsteps by enlisting in the Frunze Naval Academy at the age of 16. His entire background instilled into him from an early age a profound love of the sea and the navy, a deep sense of duty, military discipline and Soviet patriotism. But Sablin was not only a military man, he was first and foremost a Communist and a child of the October Revolution. This is what gave the inner meaning to his life and his every action.

Valery was brought up in a naval base among the sons of naval officers. His general outlook was sternly moral, as Boris Sablin one of his brothers related, he was "incapable of lying". He detested hypocrisy in all its forms. He was also incapable of witnessing any act of injustice and remain silent. From his earliest childhood he dreamed of going to sea. In 1955 at the age of only 16 Valery was accepted into the elite Frunze Military Academy in Leningrad where he became a model student. Even then he was a devoted Communist. He was voted head of the Communist youth organisation. At school he was known, probably half-jokingly, as "the conscience of the class". They somehow sensed that he was different. And they even came close to understanding wherein lay the difference. One of his classmates recalled: "We all educated to believe in socialist and communist ethics. We all believed in them. But Valery had such integrity he wanted to put these ideals into action."

These lines reveal an important truth about the Soviet Union. The bureaucratic regime that came to power after the death of Lenin was above all characterised by hypocrisy. People swore allegiance to Communism and the ideas of Lenin, when in practice the whole system was the negation of the democratic and egalitarian ideals of the October revolution. One was supposed to close one's eyes to the glaring inequalities and universal corruption, act as if these things did not exist. But this crying contradiction between theory and practice, between words and deeds, was entirely foreign to Valery Sablin's nature. From the earliest period of his thinking life he revolted against it with every fibre of his being. This fearless honesty characterised him throughout his life. Valery did not want only to make speeches about Communism; he wanted to live under Communism. He "wanted to put these ideas into action".

The Khrushchev era which followed the death of Stalin in 1953 represented a turning-point for the USSR. The death of the tyrant opened the floodgates of discontent in Russia. The ruling Bureaucracy, under the new leader, Nikita Khrushchev, moved cautiously to reform from the top in order to prevent revolution from below. But it was never Khrushchev's intention to abolish the power and privileges of the ruling caste - the millions of parasitic officials in the state, Party and armed forces who ruled in the name of the working class but who were actually, as Trotsky explained, a parasitic tumour on the workers' state.

Valery took his first political step at the age of 20, writing to the Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev a letter denouncing the social inequalities which disfigured Soviet "socialism". This was a bold and courageous action, which could have meant, at the very least, ruining his career prospects, or even worse. Unsurprisingly, the authorities were not amused. Their response was a severe reprimand, as a result of which his graduation was delayed. It is an indication of Sablin's great personal ability and tenacity that despite this setback, he succeeded in completing his studies and qualifying from military academy with honours.

In 1964, Khrushchev was deposed, and one of the top priorities of the new regime was expansion of the Soviet navy to match that of the United States. The navy was the pride and joy of the new leader Leonid Brezhnev, but the feeling was far from mutual. Naval historian Nikolai Cherkashin observed that: "The Kremlin geriatric leadership in the Politburo with Brezhnev at their head were never going to lead the country to prosperity, never mind true Communism in which Sablin believed."

Within five years, Sablin was offered the command of a destroyer, an extraordinary accolade for a 30-year-old officer. To the surprise and dismay of his family, Valery turned down the offer of a commission in favour of completing his education by enlisting in the Lenin Political Academy: an elite institution open only to military officers. Valery Sablin's love of the navy came second to his devotion to the cause of the October revolution and the working class. His refusal to accept the offer of a naval commission initially shocked his family. But his brother Boris stated that much later he understood the reason. His brother wanted to understand how the system worked from inside. He wanted to understand the nature of the beast, as a prior condition for overthrowing it.

With single-minded determinism he immersed himself in the classics of Marxism: day and night he scoured the works of Marx, Engels and Lenin in an effort to understand the revolution. Above all the young naval officer was tormented with an inner doubt that continually grew and enveloped his soul. Everywhere he looked he saw privilege, inequality and corruption that was an abomination to a true Communist. His resolve quietly grew to act to change the system. How could it be that the October revolution, which was fought in order to destroy inequality and class oppression and to give power to the working class, had ended up as a monstrous caricature, a bureaucratic totalitarian regime which had nothing in common with the democratic ideals of Lenin's State and Revolution?

At the academy, Sablin found to his dismay that certain books were still off-limits. He knew that Trotsky had been one of the main leaders of the October revolution alongside Lenin. He also knew that after Lenin's death Trotsky had led the fight against the Stalinist bureaucracy, for workers' democracy, for proletarian internationalism. But where to get hold of the writings of Trotsky and the other leaders of the Opposition? He had hoped that by joining this elite Party school he would finally obtain access to the closed archives. But his hopes were soon dashed.

Sablin confided bitterly to his brother his sense of disappointment that even here there was censorship. The political education presented by this elite institution was just as crude as the Party line he had learnt at school.

Even without access to Trotsky's writings Valery was able to draw his own conclusions. The privileged caste of bureaucrats who ran the country would never give up their power without a struggle. Sablin had made a careful study of State and Revolution and realised then that "the armour of the State and Party is so thick that even direct hits won't make a dent". he concluded that: "This machine has to be broken from the inside." The meaning of these words was revealed in the startling events of November 1975.

The navy has always been the most revolutionary wing of the armed forces. This fact is connected with the more proletarian composition of the sailors, largely drawn from the industrial proletariat. The revolutionary traditions of the sailors were shown both in 1905, in the celebrated mutiny of the battleship Potemkin and again in 1917 when the Kronstadt sailors formed the backbone of the Bolshevik forces in the revolution and the civil war. This history was well known to Valery Sablin who imbibed it, as it were, with his mother's milk. Russia's revolutionary traditions and the special role of the sailors in it became bone of the bone and flesh of the flesh of this remarkable man.

The Sentry was one of the most modern warships in the Soviet fleet. Sablin joined this submarine hunter in 1973 as second in command to its captain, Anatoly Putorny. Sablin was also the ship's chief political officer: responsible ultimately to the KGB - the dreaded secret police - he was in charge of delivering political briefings, maintaining morale and looking out for deviation from the Party line. His own "deviation" would lead to his death within just three years.

Preparations for revolt

In carrying out his duties as political officer, Sablin was obliged to deliver regular lectures on Marxism-Leninism - or rather the Stalinist caricature of Marxist-Leninism that was tailored to meet the needs of the Bureaucracy. Normally, such lectures were met by the men with an attitude of boredom and indifference, but Sablin's lectures were different. Sablin deliberately departed from the usual stilted Party texts and concentrated on other themes, particularly the October revolution, the 1905 revolution and the ideas of genuine Leninism. Even Sablin's enemies were forced to admit that he was very well-educated and well-informed.

In his lectures, he often referred to the navy's long tradition of revolution, especially the mutiny on the battleship Potemkin. The navy had only just celebrated the seventieth anniversary of this famous event and it was therefore fresh in people's minds. Naval historian Nikolai Cherkashin points out that "Sablin was continuing Bolshevik revolutionary traditions, he was steeped in these traditions. He was the flesh and bone of the Party. So his calculations were simple. He must keep faith with the revolutionary traditions of the battleship Potemkin".

Before Sablin could carry out his plan he first had to find supporters. He chose Alexander (Sasha) Shein, a young proletarian with the honest, frank face of a typical Russian muzhik who, on his own admission, was a "bit of a rebel". This 20-year old rating had been delegated to assist Sablin in preparing his lectures. Sasha Shein later effectively became Sablin's second-in-command during the mutiny. "Those political courses were a complete mockery," he states with characteristic proletarian bluntness. "People only went to them for a kip. We realised that it was completely insincere and all put on for show." These words graphically express the workers' attitude to official "Communism" in the Soviet Union. The most intolerable aspect was precisely the insincerity - the hypocrisy that infected every aspect of life and poisoned it like a contagious plague.

Under capitalism, the workers accept the existence of rich and poor as something natural and inevitable. You may not like it, but you simply have to accept it as the logical consequence of the market system. But what possible justification could there be for monstrous inequality in a system that called itself "socialist" boasted about "building Communism", that is, a classless society, the highest from of human civilisation. The contradiction between words and deeds in the Soviet Union was unbearable for any thinking person. The burning sense of injustice that arose from this contradiction lay at the very heart of the mutiny on the Sentry.

"I said to Sablin: what use is all this window-dressing?" Shein remembers, "If there is a war, who are we going to defend with all this meaningless rhetoric?" Such open cynicism was very widespread in the USSR. The only unusual thing about Shein's words are the fact that he felt able to express himself to his superior officer with such disarming frankness. Normally the political officer would be a much feared figure on board ship: a Party trustie and a KGB member, someone to spy on you and keep you under control. But the men soon found out that this political officer was something different. Sablin soon earned their respect. "The crew thought very highly of him. As chief political officer you could confide in him", recalls Victor Borodai, a midshipman on the Sentry. Sablin's relations with the men were too close for his superior's liking. He was warned to change his methods but all warnings went unheeded. Sablin was following his own agenda. Sablin's lectures had a very serious purpose: that of preparing the hearts and minds of the crew for revolt. A number of sailors became very attached to this strange "commissar" so unlike all the others. He developed feelings of respect and devotion.

On 8 November 1975, the Sentry arrived in the Baltic port of Riga, in Latvia, to take part in a military ceremony commemorating the anniversary of the Russian Revolution. Sablin decided to seize the opportunity presented by this most symbolic date in the Soviet calendar to set his plan into motion.

That night, Sablin decided to act. First he called Sasha Shein into the lecture-hall and asked him an unexpected question: "Would you be prepared to work for the KGB?" Shein's reaction was a mixture of rage and disappointment. After everything this man had taught him, now he appeared to be trying to recruit him for the secret police as a spy, a vulgar KGB informer! Shein's instinctive reaction was to walk out in disgust, but he was halted by a reassuring voice: "No, wait, Sasha, calm down, don't be angry. I was only testing you. Sit down. We must have a serious conversation."

Sablin's plan was really astounding in its audacity. He explained that the Bureaucracy had betrayed the October revolution and the Soviet people; that the regime of privilege and inequality had nothing in common with the ideas of Lenin and the Bolshevik Party, and that the only way out was a new October revolution. He explained that the Soviet working class had a revolutionary tradition and that, with a bold leadership, the workers would respond. In three days he wanted to seize control of the Sentry and sail to Leningrad. There they would issue a proclamation over the radio directed to the people of the Soviet Union to rise up against the Kremlin clique and introduce a genuine regime of Soviet democracy.

Mutiny on the Sentry

On the 8th of November, captain Putorny was informed that some of the men were drinking on board. An exceptionally diligent commander, Putorny decided to sort out the incident himself. He went below and was promptly locked in. Sablin then called the crew together and showed them a film: Battleship Potemkin, Sergei Eisenstein's inspiring account of the 1905 naval mutiny in Odessa. While the silent film played, Sablin explained his plan, exhorted the officers to support him. The officers were evenly split, eight in favour and eight against. Matters were much clearer with the ordinary sailors. The crewmen, rallied by Sablin's comrade, Alexander Shein, were unanimous in their support.

Sablin called together the officers and midshipmen and did his best to convince them. It should be remembered that at this point he did not know whether anyone would support him. The arrest of the captain shocked and scared some of them. The result was predictably mixed. Half of the ship's officers - honest and decent men who put their conscience before their personal interests - came out for the proposal. Others, like the ship's medical officer, Oleg Sadikov, refused point-blank. A typical specimen of a Soviet careerist and time-serving opportunist, Sadikov can now scarcely suppress a cynical sneer when he speaks of Sablin's revolutionary plans. He was particularly scathing about the latter's reference to Leningrad as "the cradle of the revolution". To philistines like this all revolutionary perspectives are "madness", "utopian" and "impractical". The wisdom of these clever people boils down to the philosophy of the lick-spittle and the slave who learns to love his own chains, Such people are the negation of all human progress. They exist in all countries in every historical period. If the Sablins of this world represent the face of humanity, the Sadikovs represent only its backside.

Undeterred, Sablin swept all resistance aside and demanded a vote. Here we see the crucial role of leadership. With no party and no apparatus behind him, by sheer determination, revolutionary élan and strength of character, he swept all before him. The vote for rebellion completely transformed the mood of the men. In the course of this struggle - as in every other struggle - the morale of the combatants experiences constant ebbs and flows. That is in the nature of things. The news that the crew had voted unanimously for action and that at least half of the officers had decided to back them has an immediate and electrifying effect: "From that moment on there was great enthusiasm," recalls Shein: "Everybody's spirits were lifted. We thought we would be such heroes!" he adds with a wry smile.

In fact, it is possible to say that there was an element of naiveté in Sablin's plan. One can say, with the wisdom of foresight, that it was almost certainly doomed to failure. But that would be an unfair and one-sided appraisal. Sablin was certainly no utopian. Although his plan was a risky one, it was based on a sober-minded understanding of the situation. That there was mass discontent with the bureaucratic regime is clear. It had already been demonstrated a few years earlier by a workers' uprising in Novocherkassk which had been brutally suppressed by the regime. The enthusiastic response to Sablin's proposal among the ship's crew and even a big section of the officers shows that it was based on an accurate appraisal of the mood of the masses. In order to have succeeded, an uprising would have required the unity in struggle of the sailors and workers. This Sablin understood perfectly, and that is why he developed a plan to proceed to Leningrad and try to issue an appeal on a radio frequency that could be picked up by civilians.

True, all this would have been greatly facilitated by the existence of a genuine Leninist party. But where was Sablin supposed to find such a Party? His personal experience of the so-called "Communist Party of the Soviet Union" convinced him that this was not a communist party at all, but just another arm of the bureaucratic state, a club for lackeys and careerists. Not by accident, his appeal was not to the "Communist" party but directly to the working people of the USSR. The totalitarian state, with its millions of spies and agents provocateurs had its tentacles in every factory, university and army barracks. Paradoxically, Sablin only succeeded in getting as far as he did because it was assumed that he himself, as the ship's political officer, was one of the regime's watchdogs. His position have him a unique opportunity to organise and prepare in secret. This is probably what he meant when he said that the regime could only be destroyed from inside.

Should he have refrained from taking action until he had organised an underground Leninist organisation among the sailors and then linked up with the workers in the factories? In the abstract, maybe. But Sablin knew very well the colossal difficulties facing such an enterprise. At any moment it might be betrayed to the KGB. Here, on the other hand, he had in his hands a unique opportunity to act. Sablin was no fool and certainly no madman. He took a calculated risk. It failed and he paid for it with his life. But how superior was this act of personal heroism than all the sneering of the Pharisees who merely saved their own skins and never lifted a finger in the cause of the Soviet people!

The reaction of the crew was extremely significant. Trotsky points out that the armed forces are always a faithful reflection of the tendencies within society. The rank and file navy ratings, overwhelmingly working class youngsters, were a true reflection of the mood of the Soviet working class at the time. Faithful to socialism and the ideals of the October revolution, the latter were increasingly alienated by the arbitrary and lawless rule of the Bureaucracy. The same leaders who delivered such beautiful speeches about "building communism" in the USSR lived like millionaires and princes while the living conditions of the great majority of Soviet citizens lagged far behind.

The existence of huge and growing inequalities was a constant reminder that the Soviet Union was not moving towards socialism, but on the contrary, away from it. Subsequent developments have amply confirmed this fact. The same parasitic Bureaucracy that spoke hypocritically in the name of "socialism" and "communism" at that time was later to preside over the destruction of the nationalised planned economy and the Soviet Union. The only way to have prevented this would have been the overthrow of the Bureaucracy in a political revolution to restore power to the working class. This was what Sablin tried to do.

The possibility of a political revolution against the Bureaucracy was demonstrated by the events here described. The fact that even a big section of the officers on the Sentry immediately came over to the side of the rebellion is of great symptomatic importance. It shows in miniature the process that would have unfolded on an all-Soviet scale once the working class had begun to move. The Bureaucracy - as the Marxists had predicted - would have split down the middle, and a section would have gone over to the proletariat. That a section of the officers refused to back the revolt is hardly surprising. As in every strike there were some scabs. The incredible thing is that among the ratings there was not a single scab, and only a few of the officers - the most cowardly and despicable elements - actively opposed the uprising.

These elements naturally played a pernicious role in betraying the mutiny to the authorities. Before the Sentry could leave Riga, a junior officer jumped ship and raised the alarm. The fact that their plans had been thus betrayed to the authorities caused a momentary vacillation. Faced with the possibility of having to face overwhelming odds, Sablin hesitated, but then decided to go ahead. Significantly, what stiffened his resolve was the firm attitude of the ordinary sailors, most of them still only teenagers, who insisted on continuing the revolt: "We have started this; so we might as well see it through!" The attitude of the men settled the matter in favour of action. The ship left Riga at 1am on 9 November, heading for Leningrad.

Before leaving Riga Valery wrote a letter to his wife, explaining why he had decided to risk everything. It is a most moving human document. For Valery Sablin was a man with a wife and young son, a naval officer, born into a privileged Soviet family and with a brilliant career in front of him. One can imagine with what difficulty any man would experience in such a situation. But Sablin was a revolutionary and showed no hesitation in placing his career, his family, his freedom and his life on the line for the cause in which he believed:

"Why am I doing this? The love of life. I mean not in the sense of the comfortable bourgeois, but a bright, truthful life which inspires a genuine joy in all honest people. I am convinced that in our nation, just as 58 years ago in 1917, a revolutionary consciousness will alight and we will achieve Communism in our society."

What grandeur of spirit is present in these lines! What a contrast with the pettiness, cowardice and meanness of the professional cynics of the Sadikov type!

Oleg Maksimenko, a rating, recalls that there was a strange atmosphere, a silence on board before they left port. It is like that moment of extreme tension before an athlete springs into action, when every nerve is being concentrated, like a coiled spring. On hearing the alarm that announced the ship's departure, all this energy was suddenly released.: "We were all running around like lunatics," recalled Maksimenko. "I was confused," confessed the radio operator, "What were we doing? I felt like a blind man being led around a minefield." But soon this initial confusion was replaced by a feeling of elation of men who have thrown off the yoke of slavery and raised themselves up to the height of free human beings. Maksimenko recalled: "The ship was gathering speed and this feeling of uncertainty became overwhelming. There was a feeling of freedom. A kind of contentment as if one's heart was going to take flight." During the next six hours, all kinds of contradictory feelings arose among the crew, reflecting the rapid rise and fall of their hopes and fears.

The dangers that would confront them were soon made clear: "I looked out and saw a ship coming out of the harbour," says Maksimenko, clearly reliving the experience, "I thought it was going to block us. The Sentry made a sharp turn to the right I was nearly thrown overboard; I was just clinging on. It felt as though we were at 45 degrees. And this other ship kept on coming. Then it suddenly turned left." The crew breathed easy again. The Sentry had got out of Riga!

Sablin had written the speech calling on the people of Russia to rise up and overthrow their corrupt bureaucratic rulers and create a genuinely Communist society, which he had planned to broadcast once the ship reached Leningrad. Instead, the speech was transmitted as soon as it left Riga. Immediately on leaving port, Sablin gave orders to broadcast the appeal over the ship's tannoy system on a wavelength that could be picked up by ordinary citizens. Every line of the appeal blazed with revolutionary ardour:

"I address myself," said the proclamation, "to those of you who take our revolutionary past to their hearts, to those who can think critically but not cynically about our present and about the future of our people. Ours is a purely political act. The real traitors to the Motherland will be those who attempt to stop us. In the event of a military attack on our country we will defend it loyally. But now we have another aim - to raise the voice of truth."

But unknown to Sablin, the radio operator did not dare to broadcast it as an open text and sent the speech in code &endash; it was only understood by Sablin's superiors in the naval hierarchy. Sablin's voice thus was silenced. It never reached the working class audience for which it had been written.

The Kremlin counter-attacks

The initial reaction from the authorities in Riga was one of shocked disbelief. They were slow to move - a contributing factor probably being hangovers after the celebrations the previous day. Soon, however, the realisation dawned on the authorities that something serious had occurred. "Nothing like this had ever happened before," said a high-ranking officer. "They had seized a ship. And they refused to deal with us - only with Moscow. That was bad enough. But that such a thing should be led by a Commissar!" Sablin received a direct order from the Commander-in-Chief of the navy: "Stop the ship and return to port immediately." Sablin refused. The Sentry sailed on.

The Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev was woken in the middle of the night and informed of the situation. By now the revolt had the undivided attention of the Politburo. The mood of the men in the Kremlin can only be imagined. Was this a defection? Or the beginning of a revolt? Brezhnev was taking no chances. At 4am, the captain of the Baltic Fleet was woken up and told to mobilise his ships. His orders, direct from Brezhnev, were to find the Sentry and stop it &endash; or sink it.

Thirteen heavily armed coastal vessels were sent in pursuit of the Sentry. At daybreak on 9 November, they caught up with it. The Commander issued the order to stop or be sunk. But the commander was still in some doubt as to the intentions of the mutineers. Were they really heading for Leningrad, or was the ship intending to defect to Sweden? Leningrad lies about 300 miles north-east of Riga as the crow flies. By sea, the route is double that length. The gulf of Riga is impassable to the north, closed off by the Estonian islands of Saaremaa and Hiiumaa. A ship making for Leningrad from Riga needs to head west towards Gotland, then Northwest towards Stockholm, then turn east into the Gulf of Finland. There is no way of knowing whether a ship is heading for Leningrad or Sweden until the two routes separate in the Baltic.

A coast guard vessel located the Sentry at dawn; the ship appeared to be heading for Stockholm. The KGB radioed the ship with a treacherous message, aimed at dividing the rebels: if they stopped the ship and released the commander, the men would be pardoned. Understandably, at this point there was a surge of doubt among some of the mutineers, but others remained firm and this was enough to decide the outcome. The Sentry sailed on, sending the coast guards a message: The message broadcast by the rebels began with these words: "Comrades! We are not traitors to the Motherland. We are not going abroad." Nonplussed by the mutineers' defiant message, the naval pursuers hesitated. And just at that moment, Soviet warplanes appeared overhead.

The air wing of the Baltic Fleet had orders to disable and if necessary sink the Sentry. One squadron flew over the ship, openly displaying their missiles. The commander described how he gave the fatal order: "Prepare to fire!" There was a short pause. Realising the psychological implications of his words, the commander asked the pilot if he had understood the order. "Order understood!" came the laconic reply of the squadron leader. A minute passed, seeming an eternity, then another minute. Then the shocking reality suddenly dawned on the commander. The planes had passed over the rebel ship without having discharged their missiles!

The pilots had deliberately refused to fire on their comrades. For a moment it appeared to those in command that the mutiny was spreading. The fact that pilots of the fleet air arm had refused to open fire, defying a direct order from their commander must have sent a shudder down the spine of the masters of the Kremlin. Panic broke out. The general staff stepped up the pressure for immediate action against the rebels. Shouting and cursing was heard over the airwaves. Defence minister Grechko was furious. "What's going on?" he screamed down the phone: "Carry out the order immediately!"

A second group of fighters was dispatched with different pilots who had been told god knows what story to persuade them to obey orders and attack the Sentry. Finally, the fear of their officers and the habit of blind military obedience overcame the natural reluctance of the pilots to fire on one of their own ships. "When the planes appeared it changed everything," one of the mutineers recalled. "If we did not stop we knew they would bomb us." Two fighters appeared, flying low. On board the Sentry no-one said a word; the men only stared at the skies and waited. Then the sound of gunfire was heard. For a moment some of the crew thought it was a NATO attack. Then they saw a wall of water as a bomb fell in front of them. There was a loud noise as the hull cracked. The ship lurched and started to go round in circles. Then they knew it was all over.

The fighters had dropped bombs ahead of and behind the ship. The situation was now hopeless. With the ship battered by the blasts, the resolve of the men cracked. Some of the crew opened the hatch and let out captain Putorny, who seized a pistol, ran to the bridge and shot Sablin, who was unarmed and offering no resistance, in the leg. Then the captain rang the shore in a hoarse and almost unrecognisable voice: "Cease firing. I have taken control of the ship." Less than six hours after the ship left Riga the mutiny was in ruins. By 6am, the Sentry was occupied by paratroops and KGB men. Leningrad was still 400 miles away.

The paratroopers came on board with automatic rifles. When the ship was boarded there were plain-clothes men among the new arrivals. The KGB was already taking charge. The rebels were made to stand against a wall from seven in the morning till six in the evening. Those who guarded them were ordered to shoot them in the legs if they moved. The relation between the mutineers and their guards were significant. At this stage those guarding the prisoners were ordinary soldiers. On the way back to Riga one officer asked Sasha Stein the question which must have been on everybody's mind: "Why did you do it? You broke your oath." To which Shein replied quite naturally: "Just look at how we live! What sort of a life is that? Do you really think people should have to live like this? It's just one big lie." The officer made no reply, but Shein was convinced that he agreed and even showed some sympathy.

In Riga the KGB took over the investigation. The entire crew of the Sentry were arrested, even those who had opposed the mutiny. All were sworn to silence. This measure was no accident. In Riga people were already talking of a "second Potemkin". This represented a mortal danger to the regime. The authorities did not want news of the uprising to spread and finally were therefore even prepared to present it to world public opinion as an attempted defection to the West - something that could not be further from the truth. While waiting anxiously for news of their fate, the arrested conscripts maintained their courageous defiance, assisted by the that celebrated gallows humour characteristic of soldiers everywhere. One of the sailors - a lad from Siberia - reassured them that a trip to Siberia would not be too bad, as the scenery was stunning!

Sablin, Shein and 14 others were sent to Moscow's notorious Lefortovo prison for interrogation. One of the KGB's most experienced interrogators was assigned to Sablin. The men in the Kremlin had received a rude shock. They were determined to discover what was behind the revolt. Was there an organisation? Who had led it? A true proletarian revolutionist, Sasha Shein, when asked what part he played, manfully told the interrogators that he had played an active part from the start.

In a predictable move to split the rebels, they separated the ordinary ratings from the "ringleaders". In the true style of the Inquisition, the KGB invited them to write down everything they remembered of the events on the Sentry. "Take all the time you want, even if it takes months," they were told by their gaolers. For four long months the young conscripts, nineteen or twenty years of age, were kept in isolation, with no contact with the outside world and no idea of what punishment awaited them. Eventually they were brought before a special tribunal of senior officers. The make-up of the tribunal was clearly designed to overawe and intimidate them. "More admirals and generals than you could count," one of them later recalled.

One by one the young sailors were called before the podium and asked to give account of themselves. These were not trained Marxists but ordinary young workers. Defeated and isolated, with no perspectives, most pleaded ignorance. One of the sailors commented wryly: "I'll never try that again." Upon which one of the generals ironically remarked: "You mean you'll try something else?" The assembled top brass seemed to find this amusing and smiled. The sight of a smile on the lips of the generals made the conscripts relax. "You see, they are laughing. That means they are human beings. They know we are all youngsters and will probably forgive us!" But forgiveness is not a word that featured in the lexicon of the Stalinist Bureaucracy. These sailors - ordinary working class lads - still suffered from the naiveté and inexperience of youth. They had never read Shakespeare's line: "There are daggers in men's smiles."

Sablin was still on crutches during the initial interrogation. He soon convinced his interrogators that defection was not part of his plan. But the real truth could never be admitted by the KGB. That a high-up Party official should turn against the system - this was something that must never be known. Sablin and Shein were only brought to trial nine months later. Sablin had been interrogated every day for this period. Only when his tormentors had satisfied themselves that there was no organisation behind the uprising, that it was all down to one man, did they decide to confine the punishment to the main ringleaders, Sablin and Shein. The others were all released - although they were subsequently victimised by the regime and marked for the rest of their lives. But the supreme punishment was reserved for Valery Sablin.

The scene in the courtroom was more dramatic than anything that could be invented by literature. At his "trial" which was held in camera, Sablin conducted himself with exemplary heroism. When Sasha Shein was finally brought face to face with his old comrade, he recalls how Sablin "looked at me with that piercing gaze of his, as if he was looking into my very soul. And it was if he was asking me: 'Are you still fighting or have you given up'?" Sablin was found guilty of betraying the Motherland. But the regime still had one more terrible surprise for this unbroken and defiant enemy. Although this crime usually carried a 15-year prison sentence, the Kremlin had other ideas. Such a dangerous enemy could not be allowed to live. It was Brezhnev's personal decision to have him executed by firing squad. The regime's hired judges merely repeated a verdict that had been already arrived at in advance. The trial had been a farce.

As soon as the death sentence was read out a chill ran through the courtroom. Sablin did not know about it till the last minute. Not even the investigators knew about the orders from the Kremlin. The judges read out the sentence and hastily began collecting their papers and walking out. Sablin gave them a piercing stare as if to say: "What do you think you are doing?" and under that steely stare the professional Judases of the Bureaucracy slunk out of the courtroom. Only after they had left did the exhaustion and strain of the previous months take their toll. Valery slumped forward against the barrier and had to be supported by a guard. Shein received an eight-year sentence. This was the last time he saw Valery Sablin.

Sablin was executed a few weeks after his trial. but his relatives did not find out that the execution had taken place until eight months later. They were informed of Valery's fate by a local KGB officer, one of those typical professional cynics who in every regime - democratic or fascist, bourgeois or "socialist" - are willing to perform the dirtiest tasks in order to maintain their careers and creature comforts. This creature of the regime, with his radiant smile and well-researched speech, soon destroyed their last hopes: Why was the family not informed? Because they had not asked. Now they had asked, they had been told. "As soon as you made your inquiry we sent you a copy of the death notice. And since you did not request his possessions after six months, all of them have been destroyed, including his letters and manuscripts. You can have no grounds for complaint." Everything had been done "according to the law".

Sablin was buried in an unmarked grave, the whereabouts of which has never been revealed. To this day nobody knows where he is buried. His family can only honour his memory at a monument for political prisoners.

A hero of our time

The Bureaucracy had succeeded in crushing a dangerous revolt. But just to defeat the revolutionaries was not enough. It never is. It is necessary to wipe out all trace of them and to blacken their memories. Hence the disgusting slander was invented that the crew of the Sentry wanted to defect to the West. For the next 15 years Sablin's memory was covered in dirt. The regime had prepared a lying cover-story, in which Valery Sablin - that devoted Communist and Soviet patriot - was labelled a defector and a traitor to the Soviet Union. The true facts emerged only in 1990, in the dying days of the corrupt and degenerate regime that undermined and destroyed the Soviet Union from within.

Nikolai Cherkashin explains the reason for the regime's policy of describing the rebellion as a defection: "It was very convenient for the authorities because Sablin could be disowned, treated as a defector, someone who had gone to the West for financial reasons. It was a convenient theory because it reduced the significance of this event. It wasn't a mutiny; it wasn't even a riot. it was just an ordinary criminal action."

Sablin's story is now widely known in Russia. In 1996 there was an appeal to give Sablin a posthumous pardon. The following year, Sablin was featured in the documentary series How It Was. In the West, Tom Clancy's The Hunt for Red October was a best-seller; the fictional defector Marko Ramius, played in the film by Sean Connery, had a massive popular appeal. But Valery Sablin, with his faith in the victory of the revolution, has been forgotten until now.

The crew that had followed Sablin received a variety of punishments, although none were imprisoned. "The state machine ground us all down. the 'wheels of justice' - unjust as they were - affected all of us, even the officers, regardless of seniority." In the words of the Sentry's radio operator, "Our careers were ruined. We all lost our jobs, our love of the sea, our passion to defend the Motherland, it was all crushed. The machine broke everyone's lives." Yet in spite of everything, the memory of the revolt still evokes feelings of pride. Twenty five years since these remarkable events, the surviving members of the crew met to commemorate the mutiny. There was no trace of regret, no apologies or excuses. "We are proud of what we did", they say. And Sablin? "The man was a hero," they say, "he should have had a medal." In a moving tribute to his old comrade at the close of the documentary Sasha Shein pronounces the following judgement: "Every society needs noble spirits, without them, no society can move forward. Sablin was such a noble spirit."

The Channel Four documentary is a wonderful document. Yet it obviously has its weaknesses. Not being written by Marxists, it has no real understanding of the political significance of the events which it so honestly and movingly portrays. The issues are mainly given a human interest, which is valid within certain limits but which is not enough. Certainly, if Sablin himself would have lived to see it, he would doubtless be grateful but highly critical, particularly of the programme's conclusions which would appear to be that the mutiny on the Sentry was a heroic but hopelessly doomed episode - an historical curiosity, like Sablin himself: "Even after his death," the documentary concludes, "Sablin remains an enigma: a loyal Communist who dared to stand up to the state."

But for any person acquainted with the history of the USSR, there is no enigma here. Sablin was not the isolated individual painted by this programme. He is one of a gallery of heroes of the Russian revolutionary movement who fought and died in a struggle to rescue the traditions of October and who entered into a life-and-death struggle against the Stalinist Bureaucracy. The men and women who began this struggle were the members of Trotsky's Left Opposition in the 1920s, who perished in Stalin's death camps and the dungeons of the GPU-KGB.

Nor was Sablin the only example of a high-ranking Communist who was prepared to stand up to the Stalinist tyranny and defend a Leninist policy. Even in the ranks of Stalin's GPU there were such people - dedicated Communists willing to give their lives for the Revolution. In 1937, Ignace Reiss, a high-ranking officer in the GPU openly declared for Trotsky and called for a political revolution against Stalin, the gravedigger of the October Revolution, like Valery Sablin, Ignace Reiss was murdered by the Bureaucracy. And for every one of these heroes whose name we know, there have been a hundred and a thousand who have no name and no grave.

In the days before his execution, in that dark night of isolation on the brink of the abyss, Sablin was allowed by his tormentors to write a final letter to his only son. This remarkable document were the last words Valery Sablin was able to utter to the world before being silenced forever. These words, so full of optimism and confidence in the future of humanity, are his last will and testament. They still ring out like a clarion-call to future generations:

"Trust the fact that history will judge events honestly and you will never have to be embarrassed for what your father did. On no account ever be one of those people who criticise but do not follow through their actions. Such people are hypocrites - weak, worthless people who do not have the power to reconcile their beliefs with their actions. I wish you courage, my dear. Be strong in the belief that life is wonderful. Be positive and believe that the Revolution will always win."

Today, when the Stalinist regime of the USSR has been replaced with an even more monstrous capitalist regime, the oppression suffered by the masses in Russia is a thousand times worse than in 1975. But out of all this suffering, a new spirit is being born: a spirit of revolt against the existing order that takes as its point of reference the glorious revolutionary traditions of Russia's past. Alongside the numerous revolutionary heroes of 1905 and 1917, the new generations of workers and youth will find their inspiration in the life and work of Valery Sablin, that hero and martyr of the Russian working class and international socialism.

The traitors to Communism tried to wipe out his memory by scattering his ashes to the wind and blackening his name with lies and filth. Now the same people who dared to sit in judgement on a brave and sincere defender of the traditions of October have destroyed the USSR and themselves defected to capitalism. On the shoulders of the new generation of Russian workers, soldiers and youth lies the task of finishing the job begun 25 years ago by Valery Sablin and his comrades. Let the new generation clean away the dirt and revere the memory of a man who gave his life to the greatest cause of all - the cause of socialist revolution.