Art

It is sometimes said that Marxists are only interested in pouring over economic data and political analysis – that we have no interest in art and culture. Nothing could be further from the truth. By striving for the end of capitalism and freeing men and women from exploitation, we seek to give ordinary workers more time to enjoy and participate in culture, and raise art to new heights.

It is sometimes said that Marxists are only interested in pouring over economic data and political analysis – that we have no interest in art and culture. Nothing could be further from the truth. By striving for the end of capitalism and freeing men and women from exploitation, we seek to give ordinary workers more time to enjoy and participate in culture, and raise art to new heights.

Art under capitalism is shackled to the profit motive. Culture is a business, and many of humanity’s finest works of art, music and literature are locked up in private collections or reserved for the wealthy. Moreover, art has become increasingly shallow and pedestrian, reflecting the crisis of the capitalist system itself. Rather than empowering artists to experiment and develop new ideas, billions are thrown at derivative dross by a shrinking handful of media monopolies. The rot of capitalist society is reflected in a rotten culture.

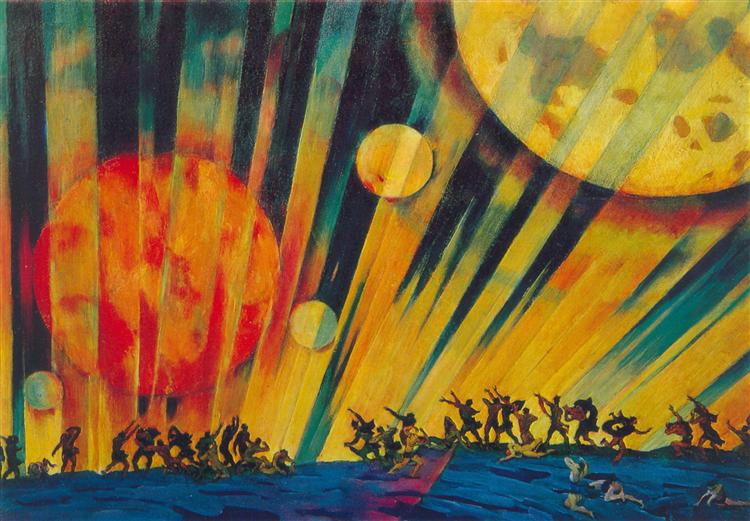

The solution to art's problems is not to be found in art itself, but in society. The Russian Revolution saw a flood of creativity as artists took inspiration from the heroic struggle of the masses against Tsarism and capitalism. The Bolsheviks flung open the gilded doors of Russia’s galleries and opera houses to ordinary people for the first time. This is our inspiration. By breaking with the capitalist system and returning culture to the people by investing in education and the arts, as Trotsky puts it: “The average human type will rise to the heights of an Aristotle, a Goethe, or a Marx. And above this ridge new peaks will rise.”