After 12 years of upheavals, war, carnage and betrayals, the revolution which broke open in 1791 in Saint-Domingue finally succeeded in abolishing slavery and achieved independence in Haiti. This revolution was the consequence and the prolongation of the French Revolution. Its successive stages, marked by numerous shocks and turnarounds, was largely determined by the flux and reflux of the French Revolution.

The history of the revolution is indeed full of heroism and sacrifices. The insurgent slaves finished by defeating, each in turn, the great European powers like Spain, England and France. But it is also a history of greed, cynicism and inhumane cruelty on the part of the ruling classes.

The revolution in Saint-Domingue deserves to be better known amongst the workers and youth of our epoch. It is in the remarkable book by C.L.R James, The Black Jacobins, written in 1938, where on can find the most serious and complete analysis. We cannot but trace the general lines here.

After the arrival of Christopher Columbus on the coasts of the island, which he called Hispaniola, a Spanish colony was founded in the Southwest of the island. The colonizers brought with them Christianity, forced labour, massacres, as well as rapes and pillages. They also brought with them infectious diseases. To subdue the rebel indigenous population, they organized famines. The consequence of this “civilizing mission” was a dramatic reduction of the indigenous population, which dropped from 1.3 million to only 60,000 in the space of 15 years.

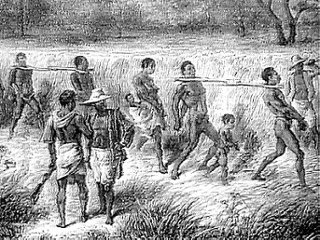

With the signing of the 1695 Ryswick treaty the western part of the island went to France, and in the course of the 18th Century, the slave trade was massively developed. Captured in Africa and taken by force, the slaves crossed the Atlantic in chains and stuffed in the suffocating hold of the slave merchant vessels. This commerce displaced hundreds of thousands of Africans to America and West Indies, where they were delivered into unfathomable cruelty at the hands of their white owners.

Branded by a hot iron, the slaves were subjected to the whip, mutilations and all sorts of physical abuses. Their owners bragged about the “sophistication” of the methods of punishment and execution. They poured burning wax over their heads. They made them eat their own excrement. Those condemned to death were burned alive or died attached to the “four posts” with their stomachs opened, while the dogs of their masters ate their entrails.

The French bourgeois enriched themselves from this brutal exploitation and from all the abominations necessary for their perpetuation. The owners of Saint-Domingue had been corrupted by the power of life and death they held over this growing mass of human beings. The fortune of the maritime bourgeoisie, constructed on the slave trade, was in part invested in the colony. With its agents and negotiators, as well as the sons of impoverished nobles and various merchants, this class of owners formed the elite strata of colonial society, under which were located the clerks, the notaries, the lawyers, managers, the bosses and owners as well as the artisans.

“There was not a place in the world as miserable as a slave ship”, we read in The Black Jacobins, “no area of the world, considering its entire surface, which possessed as much wealth as the colony of Saint-Domingue.” Thus, numerous “little whites” – day workers, urban vagabonds and criminals – went to Saint Domingue in the hopes of making a fortune there and to be respected in a way not within of their grasp in France. For the maritime bourgeois of Nantes and Bordeaux, the abolition of slavery signified ruin. It was the same for slave owners on the island. And in the eyes of the “little whites”, the maintenance of slavery and racial distinctions was essential. Many times in the history of the colony, they showed that they would not shy away from any atrocity in order to preserve them.

A tiny fraction of the blacks, coachmen, cooks, nannies, domestics etc., escaped the permanent ordeals that the mass of slaves were subjected to, and were even able to acquire a little education. It is from this fine social layer that the majority of the revolutionary leaders came from, including Toussaint Bréda, the future Toussaint Louverture.

Toussaint’s father arrived on the island in the hold of a slave ship, but he was lucky enough to have been bought by a colonist who accorded him certain liberties. The first born of eight children, Toussaint had as a godfather a slave by the name of Pierre Baptiste, who taught him rudimentary French. He became a shepherd and then a coachman. Among the books that Toussaint could read was The philosophical and political history of the Establishments and the Commerce of the Europeans in the two Indias, published in 1780 by the abbé Raynal. Convinced that a revolt was about to break out in the colonies, the abbé wrote: “Two colonies of black fugitives exist already. These flashes announce the thunder. Only a courageous leader is missing. Where is he? He will appear suddenly, of that we have no doubt. He will come brandishing the sacred flag of liberty.”

When the French Revolution broke open, the “little whites” saw it as an opportunity to strike a blow against the royal authority and have themselves recognized as the masters of the island. For a long time, they advocated the extermination of the mulattos – of “mixed blood” – whose property they wanted to appropriate. Numerous mulattos had been incorporated into the militia of the Royal Authority, which relied on them in order to resist the revolutionary “agitation” of the whites.

The demeaning conditions of the immense majority of slaves engendered a fatalism and indifference towards their personal fate. However, acts of resistance were not rare. These would take the form of an “escape” through suicide or the poisoning of slave-owners, their wives and their children.

The slaves who fled their masters hid in the mountainous and forested regions, where they formed groups of free fugitives called “marrons” (runaways). In the middle of the 18th century, one of these, Makandal, planned to cause and uprising of the blacks en masse and chase away the colonists. His plan was to poison the water of all the houses of the colonists. His plan was never executed. Betrayed, Makandal was captured and burned alive in 1758.

In 1790, the French Revolution was at a low ebb. The maritime bourgeois, which was predominant in the National Assembly, found that it had gotten something out the established compromise with the monarchy, and didn’t wish to see the revolution spread further. They refused to recognize the rights of the mulatto, out of fear of opening the possibilities of a revolt of the black slaves. However, the same as the conflict of interest between the bourgeois and the monarchy in France opened the space for the action of the Parisian masses, the conflict between the whites and the mulattos of Saint Domingue opened the revolution of the slaves, which broke open on the night of the August 22-23, 1791.

The instigators of the insurrection met along with their leader Boukman in the forest on the mountain Morne Rouge under the light of torches and the rain of a tropical storm. After having drank the blood of a pig, Boukman recited a prayer: “The God of the whites inspires them to commit crime but our God pushes us to commits acts of good. Our God, good to us, orders us to avenge ourselves of our received offences. He directs our weapons and aides us”. In a few hours, the insurrection had laid waste to half of the northern plain. The slaves destroyed and killed incessantly with the cry of “Vengeance! Vengeance!”.

Toussaint Louverture had joined the insurrection a month after the debut of the insurrection, and became, along with Biassou and Jean-François, one of the leaders of the movement. The rebelling slaves dominated the fields of battle). Facing the defeat of the insurrection, its leaders, including Toussaint, were getting ready to abandon the struggle in exchange for the liberty of some 60 leaders. But the owners didn’t want to hear anything of it. There was no possibility of compromise. Thus from then on, for the revolutionary army, of which Toussaint had rapidly become the uncontested leader, it was a question of liberty or death! Toussaint Louverture (1743-1804)

Toussaint Louverture (1743-1804)

The French government sent a military expedition, lead by General Sonthonax, to re-establish order on the island. However, before they arrived in Saint Domingue, the Parisian insurrection of August 10 1793 overthrew the monarchy and drove out the representatives of the slave-owning bourgeois. This new phase of the French Revolution had immense consequences for slaves Saint-Domingue, because the armed popular masses, on whom the revolutionary power rested, were in favour of the abolition of slavery. For the first time, the slaves of Saint-Domingue had powerful allies in France.

Toussaint and his army of slaves aligned themselves behind the Spanish in order to battle the armed forces sent from France. After having reorganised his troops, Toussaint had taken a series of towns. The British, profiting from the difficulties of Sonthonax, took control of the entire west coast, with the exception of the capital. Overwhelmed on all coasts and threatened with defeat, Sonthonax sought the support of Toussaint against the British. To this end, he would go as far as to decree the abolition of slavery. But Toussaint was suspicious. What was the attitude of Paris? Had Sonthonax not been sent to “re-establish order” on account of the slaves? It was not until Toussaint learned of the decree of February 4 1794 abolishing slavery, that he turned against the Spanish and joined Sonthonax to fight the British.

The authority and power of Toussaint Louverture, now and officer in the French army, never ceased to grow. With 5000 men under his command, he held a fortified position between the north and west of the island. The British forces and the Spanish, on the opposite side, had superior arms and provisions. They also had the mulatto forces commanded by Rigaud, who was in cahoots with the British.

Nearly all of Toussaint’s soldiers were born in Africa. They did not speak French, or very little. Their officers were former slaves, like Dessaline, who wore the scars of his former masters’ whips under his French army uniform. The source of their force came from their revolutionary enthusiasm and their fear of the restoration of slavery. Their principle weapons were the watchwords of the revolution: liberty and equality. This gave the former slaves a colossal advantage over their adversaries, who were fighting for interests that were not their own. Poorly armed and starving, the former slaves showed proof of extraordinary courage and combativeness under fire from the enemy. When they were lacking ammunition, they would battle with stones or their bare hands.

The struggle for liberty became a pole of attraction for all the oppressed of the island, which gave Toussaint a mass social base. When a certain Dieudonné, who was at the head of several thousand “runaways”, who was about to go over to the side of the mulatto generals Rigaud and Beauvais and their British allies, Toussaint addressed a letter to him in order to expose his error: “The Spanish were able to blind me on several occasions, but it was long before I recognized their rapacity. I abandoned them and fought them well [...] If it is possible that the English succeed in deceiving you, my dear brother, abandon them. Unite with the honest republicans, and drive out all the royalists from our country. They are rapacious, and want to throw us back to the branding irons that we have so much difficulty breaking.”

This letter was read to the troops of Dieudonné by an emissary of Toussaint. The blacks who were listening immediately denounced the treachery of Dieudonné, who was arrested and thrown in prison. As James wrote about this incident: “Proof that despite their ignorance and their incapacity to recognize it in the middle of the mass of proclamations, lies, promises and traps that surrounded them, they wanted to fight for liberty.”

Meanwhile, in France, the revolutions had reached its limits. The inferior classes of society who were the motor force of the revolution, could not overstep the limits of the bourgeois order, and the reaction raised its head. After the fall of the Jacobins, it was the enemies of the slaves, and notably the maritime bourgeois, who returned to power.

Toussaint sensed that the winds were changing. Sonthonax, himself conscious of the danger of a restoration of slavery, proposed to Toussaint that the white colonists be driven definitively driven off the island. Toussaint refused this proposition, and finished by sending Sonthonax back to France. This gesture caused the Director to suspect Toussaint of orienting towards independence, which wasn’t the case. Toussaint feared in fact that France sought to re-establish slavery.

To reassure the Director, Toussaint sent a long and remarkable letter, assuring him of his loyalty. It was however a question of loyalty to the ideas of the revolution and the emancipation of the slaves. “France will not renounce its principles, she will not take away the largest of her benefits from us, she protects us from our enemies, [...] she will not allow the decree of 16 Pluviôse, which is a joy for humanity, to be revoked. But if, to re-establish slavery in Saint-Domingue, if one does that, I declare to you, that would be to attempt the impossible; we have faced dangers in obtaining our liberty, and we know that we will face death in order to maintain it”.

In place in Saint-Domingue, Toussaint again overcame the armies of Great Britain, who had already paid a heavy tribute to the revolutionary willingness of the former slaves. At the end of 1796, the war had killed 25,000 British soldiers and injured 30,000. Faced with such losses – and no tangible results – the government of His Majesty decided to withdraw and conserve only the Port of St. Nicholas and the Ile de la Tortue. But Toussaint would not even accord them this symbolic presence. With Rigaud, the mulatto general who after a while had become his ally, he launched an offensive on a grand scale which left the British general Maitland no choice other than to evacuate the entire western part of the island. Slave trade in Africa: forced on a slave ship

Slave trade in Africa: forced on a slave ship

In July 1797, the Director appointed general Hédouville as the special representative of France in Saint-Domingue. The general’s mission was to reduce the power and military capacity of Toussaint while waiting for military reinforcements. He arrived to Saint-Domingue in April 1798 at the moment that Toussaint defeated the British.

Hédouville concluded an accord with Rigaud, who once more, turned against Toussaint. Facing provocations and threats from Hédouville, Toussaint ordered Dessalines to attack him. Dessaline’s sudden campaign forced Hédouville to beat a hasty retreat from Saint-Domingue, accompanied by a thousand functionaries and soldiers. Toussaint and Dessalines could then turn their attention to Rigaud in the south. After the defeat of the mulattos, Toussaint ruled the colony.

Napoléon Bonaparte, now in power, could not but recognise the authority of Toussaint, and confirmed him as commander-in-chief of Saint-Domingue. Rigaud, who was shipwrecked on his return to France, did not arrive there until 1801. Napoléon received him and told him: “General, I do not blame you but for one thing, that you did not know victory.” On his part, Toussaint proposed giving the administration of the south to the mulatto Clairevaux – who refused – and then to Dessalines, who had 350 mulatto soldiers executed. It was not possible for him to tolerate the presence of uncertain and dubious elements faced with the threat of a new French expedition to the island.

After the British under Maitland, the French under Hédouville and the mulattos under Rigaud, it was from now on the turn of the Spanish, in the east of the island, to face the power of the former slaves. On January 21 1801, the Spanish governor had to order the abandonment of the colony.

Saint-Domingue was thus bled dry. Of the 30,000 whites who lived on the island in 1789, there were now only 10,000, and of the 40,000 mulattos, there were only 30,000. The blacks, of which there were 500,000 at the beginning of the revolution, were now no more than 350,000. The plantations and crops had been largely destroyed. But the new regime, which rested on now on a mass of independent peasants, was much better than the old regime. The reconstruction and the modernisation of the country could finally begin. Above all, the revolution had created a new race of men, among whom the feeling of inferiority that the slave-owners had inculcated had disappeared.

In France, however, the maritime bourgeoisie wanted to recover the fabulous profits from the pre-revolutionary epoch. In order to satisfy them Napoléon decided to re-establish slavery over the blacks and discrimination against the mulattos. In December 1801, an expedition of 20,000 men headed for Saint-Domingue, under the command of Napoléons brother-in-law, general Leclerc.

In the course of all the reversals and changing of alliances, it was never a question of independence for Toussaint. As the expedition approached, the whites everywhere demonstrated their enthusiasm at the perspective of the re-establishment of slavery. But Toussaint did not want to admit the truth concerning the intentions of Napoléon. He was convinced that a compromise was still possible, and took no action.

The frustration of the former slaves in the face of certain aspects of Toussaint’s policies caused an insurrection, in September 1801. Toussaint must be criticized and reproached for favouring the whites in order to maintain relations with France. Toussaint had Moïse, his adoptive son or “nephew”, who was revered by all the former slaves as a hero in their war for liberty, executed.

Instead of explaining clearly the objectives of the expedition, purging his army of dubious and uncertain elements and suppressing the whites who called for the return of slavery, Toussaint suppressed those in his own camp who, like Moïse, understood the danger and wanted to act accordingly. This explains the falling apart, the massive defections and the disastrous confusion that reigned in his camp at the moment of the landing, thus we saw the initial success of Leclerc’s troops.

As soon as the extent of the disaster became evident, Toussaint regained self control. The resistance finally began to organise to the point of containing the advance of the French forces. With the arrival of the rainy season and yellow fever, the losses inflicted on the French put Leclerc, himself exhausted and sick, in a particularly precarious situation. The incredible bravery of the former slaves in the face of death affected the morale of the French soldiers, who wondered whether justice, in this war, was really on their side.

While fighting the war vigorously, Toussaint considered the conflict with France a veritable disaster. That is why he combined excessive war in the field with secret negotiations with the enemy. He hoped for a compromise, and the French command profited from this weakness. Leclerc proposed a peace accord, according to which Toussaint’s army would be reintegrated into the French army while maintaining its generals and rank. This accord was matched with a guarantee that slavery would not be re-established. Toussaint accepted this. But in reality, Leclerc needed time. He was waiting for re-enforcements which, he thought, would allow him to exterminate Toussaint’s troops and re-establish the regime of slavery.

In spite of the accord concluded with Toussaint, the resistance continued. As soon as the resistance was pacified in a certain region, the resistance would appear in another. Yellow fever killed French soldiers by the hundreds. Leclerc feared that the black troops placed under his command by the accord would defect.

On June 7 1882, Toussaint was called to a meeting with general Brunet. Upon arrival he was seized, chained up, and thrown along with his family into a frigate and taken back to France. He died from cold and from mal-treatment at Fort-de-Joux, in the Jura, in April 1803. But this arrest didn’t solve anything for Leclerc. The following month, out of breath and exhausted, he implored Paris to replace him and to send re-enforcements. Of the 37,000 French soldiers who had come to the island on successive landings, only 10,000 remained, of which 8,000 were in hospital. “The illness continued and wreaked havoc,” wrote Leclerc, “and dismay exists amongst the troops of the west and the south.” In the north the resistance was developing.

Leclerc kept secret Napoléon’s orders concerning the re-establishment of slavery. But at the end of July 1802, several blacks onboard the frigate La Cocarde, arriving from Guadeloupe, threw themselves into the sea and swam to the shore to bring the news to their brothers in Saint-Domingue: slavery had been re-established in Guadeloupe.

The insurrection in Saint-Domingue was immediately general. And yet, for a certain time, the black generals and the mulattos didn’t join the insurgents. The blacks of Saint-Domingue were hoping that their loyalty would help them avoid the fate of the blacks of Guadaloupe. They even participated in the repression of the “robbers”. Finally, it was the mulatto generals Piétons and Clairveaux who were the first to pass to the side of the resistance. Dessalines was not long in following their example.

Rochambeau, who replaced Leclerc after his death, in November 1802, lead a veritable war of extermination against the blacks, who by the thousands were shot, hanged, drowned, or burnt alive. Rochambeau demanded the sending of 35,000 men to finish his work of extermination, but Napoléon could only send him 10,000.

To economize his munitions and for his own amusement, Rochambeau had thousands of blacks thrown from French frigates, into the Baie du Cap. So that they would not be able to swim, the decomposed bodies of blacks who had been shot or hanged were attached to their feet. In the basement of a convent, Rochambeau laid out a scene. A young black man was a attached to a post under the amused looks of bourgeois dames. The dogs, who were to eat him alive, hesitated, without doubt frightened by the military music that accompanied the spectacle. His stomach was open with the slash of a saber, and the hungry dogs then devoured him.

It was less a war of armies than one of populations, and the black population, far from being intimidated by the methods of Rochambeau, confronted them with such courage and such firmness that they scared the executioners. Dessalines did not have the scruples that Toussaint had vis-à-vis France. His key word was “independence”.

Dessalines delivered blow after blow, massacring practically all the whites he found on his way. The offensive of the blacks under his command was of irresistible violence. The war took the allure of a racial war. However, its real cause was not to be found in the colour of the skin of the combatants, but in the thirst for profits of the French bourgeois. On November 16, the black and mulatto battalions were grouped for the final offensive against the Cap and the fortifications that surrounded it. The power of the assault forced Rochambeau to evacuate the island. On the day of his departure, November 29 1803, and preliminary declaration of independence was published. The final declaration was adopted December 31.

Toussaint Louverture was no more, but the revolutionary army that he created showed itself, once more, capable of defeating a great European power. The leaders of this army, as well as innumerable unknown who fought and died to get rid of slavery, deserve all that we can remember of their struggle. Taking the expression of the author of The Black Jacobins, the slaves who carried out the revolution in Saint-Domingue were true “heroes of human emancipation”.