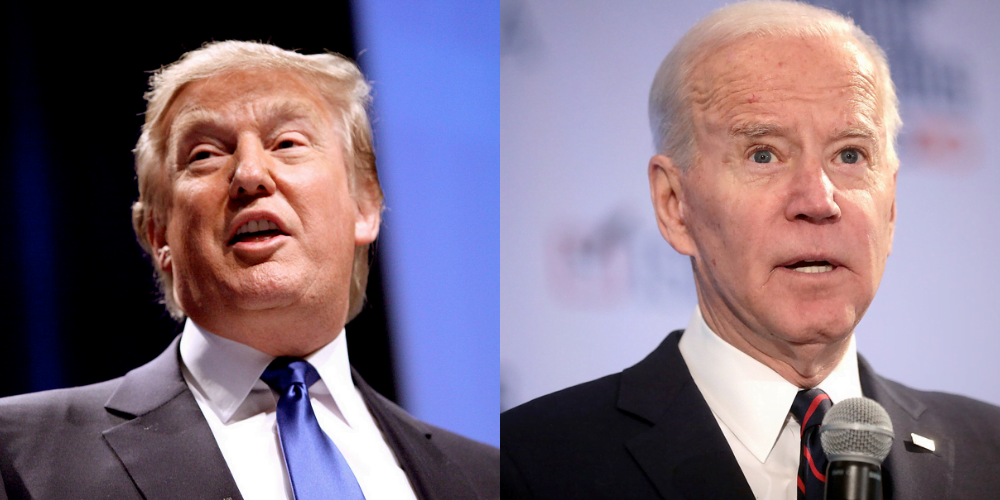

Fred Weston, editor for marxist.com, explains how the Italian left wrecked itself on the rocks of 'lesser-evilism', starting in the 1970s. With early voting for the US elections underway, and huge pressure on the left to vote for Joe Biden in order to kick out Donald Trump, there are valuable lessons to be learned from the Italian experience.

There is huge pressure on the left in the United States to come out in support of Biden in the presidential elections. Even former hardline socialists who would never have contemplated voting for the Democrats in the past are falling over themselves to explain how “things are now different”. The difference being of course that “now we face the threat of fascism” in the form of Trump. Never has so much confusion been sown under the sun!

This idea is argued for and defended even by many who say they are socialists and would like to see a third party emerge: a genuine party of the left. However, because they see the perspective of such a third party as being very far away, they content themselves with the idea of working within the Democrats, supporting them in elections, and so on, and then at some distant time in the future, the conditions will be created for a break with them. That is how the story goes.

What is missing here is a more global and long-term view of the problem. It is true that if Biden wins, Trump loses. But what will Biden do if he wins? Will he carry out a “progressive” policy in defence of the income, jobs, housing, education, pensions of working-class Americans? Ask a child of six and they know that is not the case. Biden is the candidate of the US ruling class, and he will attack the living standards of ordinary working Americans if he wins. And anyone who supported him will be tainted with his policies. How this can be presented as a strategy towards building a third, working-class based party in the United States is anyone’s guess.

What lies behind this approach is the idea of “lesser-evilism”, i.e. that you vote for the least bad candidate in order to stop the more extreme right wing from taking control of government. In the United States this idea is being posed in the context of debate on the left of how to build a third force that can break the decades old two-party system and offer a genuine alternative to the American workers.

The idea of “lesser-evilism”, however, is not just an American phenomenon. It has appeared many times in many different countries. Italy is one prime example, a country that had the largest Communist Party in Western Europe, the PCI, with two million members and 34 percent of the vote at its peak in 1976. This article is about how lesser-evilism destroyed that once mighty party, and how Italy ended up where it is now, without a genuine mass workers’ party.

The 1970s

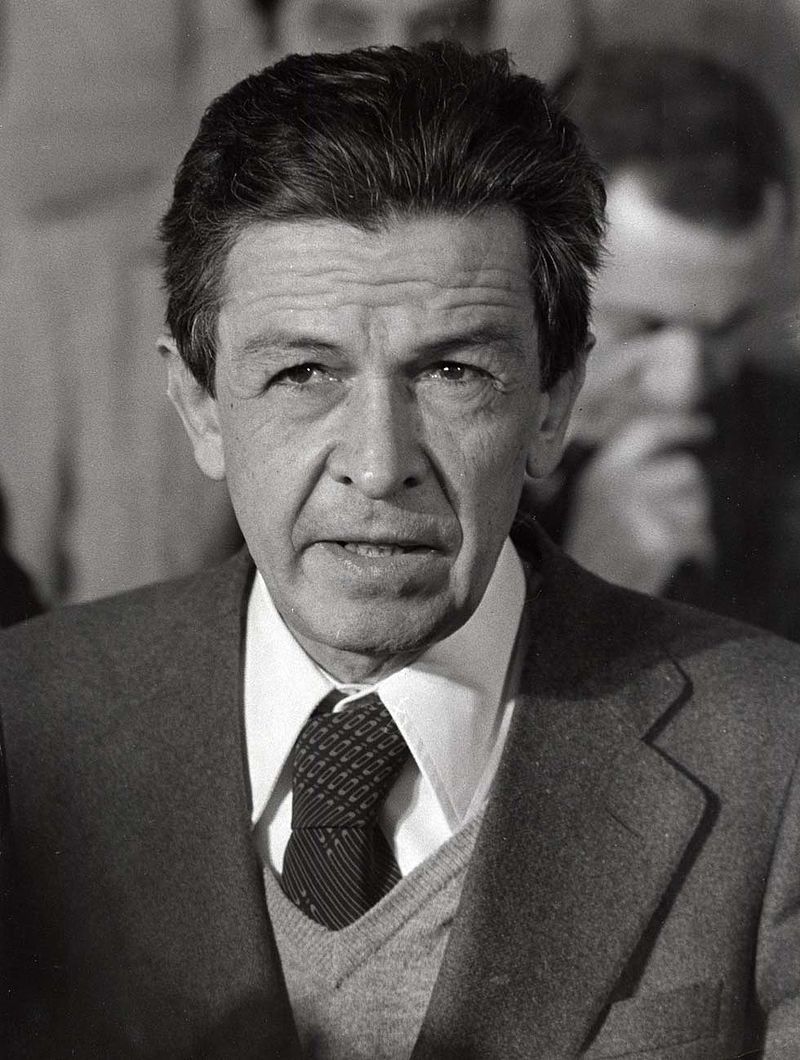

The basic position of the PCI in the 1970s was that, to avoid the threat of fascism in Italy, it was necessary to form a grand alliance of all the “democratic forces”, mainly with the Christian Democratic Party / Image: public domain

The basic position of the PCI in the 1970s was that, to avoid the threat of fascism in Italy, it was necessary to form a grand alliance of all the “democratic forces”, mainly with the Christian Democratic Party / Image: public domain

We want to concentrate mainly on what happened in the 1990s and 2000s, but it is also worth providing a brief outline of what happened earlier in the 1970s, because the DNA of lesser-evilism was already built into the thinking of the leaders of the old PCI, which was then passed on to the leaders not only of the PDS [Democratic Party of the Left] but also of Rifondazione Comunista [Communist Refoundation], after the dissolution of the PCI in 1991.

The end of the 1960s saw a massive surge of working-class militancy in Italy which produced the famous Hot Autumn of 1969. This opened up a decade of intense class struggle, which saw the unions almost double their membership and the Communist Party (PCI) surge forward at every election. In 1976 the PCI won over 34 percent: its highest vote ever. The movement of the working class seemed unstoppable.

The tragedy of the whole situation was to be found in the ideas elaborated by the leadership of the PCI at the time under Enrico Berlinguer. The 1970s saw intense class struggle globally, but it also saw defeats, the most important of which was in Chile in September 1973, when General Pinochet launched a coup, smashed the labour organisations, arrested, tortured and killed thousands, and set up a brutal military dictatorship. The leadership of the PCI used the events in Chile to argue for a shift in strategy, and elaborated the idea of the “historic compromise”.

The basic position was that, to avoid the threat of fascism in Italy, it was necessary to form a grand alliance of all the “democratic forces”, mainly with the Christian Democratic Party. An example of how Berlinguer argued his case is the following quote from an article he wrote, Alleanze sociali e schieramenti politici (Social alliances and political alignments) published in Rinascita on 12 October 1973:

“…how to ensure that a programme of profound social transformations – which necessarily determines all kinds of reactions on the part of backward groups – is not carried out in such a way as to push vast layers of the middle classes into hostility, but instead receives, in all its phases, the consensus of the great majority of the population.”

He warned of a danger of provoking “a real split in two of the country, which would be fatal for democracy and would overwhelm the very basis of the survival of the democratic state.” And he warned that, even if the left as a whole were to win 51 percent of the vote, this would not be enough.

“This is why we are speaking not of a ‘left alternative’ but of a ‘democratic alternative’, that is, the political perspective of a collaboration and understanding of the popular forces of communist and socialist inspiration with the popular forces of Catholic inspiration, as well as formations of other democratic orientation.”

Berlinguer depicted a utopian scenario where the “privileged pay to the necessary degree” and where a process of “deep and general redistribution of wealth” would take place without challenging capitalism itself.

We see here how the ranks of the PCI were being prepared for a class-collaborationist policy on the part of the leadership. The scarecrow of the “danger of fascism” was used to justify the idea of governing with the Christian Democrats. The “lesser evil” was a government with the Christian Democrats, the greater evil being fascism.

Thus, when the Christian Democratic government of Andreotti proceeded to impose austerity measures in late 1976, the Communist leaders in parliament backed it and sold the idea that this was a necessary but temporary sacrifice the working class had to make. Without actually being a part of the coalition government headed by the Christian Democrats, the PCI leaders initially provided external support to Andreotti, but later joined the government’s parliamentary majority, taking full responsibility for its policies.

Far from opening up a period of wealth redistribution, the workers paid heavily, while the capitalists continued to make profits at the expense of the working class. This marked the end of the rising popularity of the Communist Party. The PCI leaders were used by the ruling class between 1976 and 1979 and then they were discarded. In the 1979 elections, the PCI entered what was to be a long-term decline, winning just over 30 percent, falling below 30 percent in 1983, and less than 27 percent in 1987. The layers that had been won in the course of the late 1960s and early 1970s now abandoned the party, disillusioned.

Split in the Communist Party

However, what was to come a few years later was to prove to be an even worse disaster. With the collapse of Stalinism in Eastern Europe and later in the USSR, the PCI leaders were able to push for something many of them had been dreaming of, but which would have been difficult to get the ranks of the party to swallow: the abandonment of the very name Communist. The idea was that the decline in popularity of the PCI was due to its identification as Communist. What was needed was something more “modern”. They came up with the name of the Democratic Party of the Left (Partito Democratico della Sinistra, PDS).

When they held their congress in January 1991 to decide on the change of name, the party split in two, with one wing refusing the abandonment of the Communist name and then going on to form Rifondazione Comunista (Communist Refoundation). In the 1992 election, the PDS won only 16.1 percent, with Rifondazione taking just under 6 percent. The combined vote of the two wings of the former Communist Party had now gone down to 21 percent. Clearly, it was not the name of the party that had caused its decline, but years of compromise and class collaboration.

Things, however, were about to dramatically change Italian politics even more. On 17 February 1992, the judge Antonio Di Pietro had Mario Chiesa arrested. He was a member of the PSI, the Italian Socialist Party, which at the time was in a coalition government with the Christian Democrats. Chiesa was arrested for accepting a substantial bribe from a cleaning company. In order to avoid the scandal from affecting the fortunes of the PSI, its then leader Bettino Craxi tried to distance the party from Chiesa, calling him a thief.

Chiesa was not too happy with this treatment – as he was fully aware of the fact that corruption went all the way to the top of the party – and he began to spill the beans on many party leaders involved in corruption. This is not the place to analyse what became known as the Tangentopoli scandal [literally ‘Bribe-opoly’], but it was the beginning of the Mani Pulite [‘Clean Hands’] operation, which would see top leaders of not only the Socialist Party, but also of the main bourgeois party, the Christian Democracy, exposed for rampant corruption. The end result was that these parties collapsed as the masses turned away from them in anger.

The PSI disappeared very quickly, as it was at the heart of the corruption scandal, with its leader Bettino Craxi preferring to go into exile in Tunisia. The Christian Democracy suffered huge electoral setbacks in the 1993 local council elections, winning only 9 percent in Milan, 12 percent in Rome, 12 percent in Turin and 9.9 percent in Naples. Apart from Milan, where the Northern League made a big breakthrough, most of the major cities were won by coalitions in which the main party was the PDS, and sometimes Rifondazione Comunista was also part of the alliance.

A vacuum had emerged on the right. The main parties that the Italian bourgeoisie had used to govern Italy had all but collapsed. From the outcome of the 1993 council elections it seemed that coalitions involving the PDS as the main party were the only options left to the ruling class. Articles appeared in the serious bourgeois press weighing up this possibility. For some sections of the Italian capitalist class, however, the idea of the former Communist Party being at the head of government was like a red rag to a bull.

The rise of Berlusconi

That is when Berlusconi, with huge financial resources based on his business network, launched a new party, Forza Italia, and went on to win the March 1994 elections with close to 43 percent of the votes in an alliance with the Northern League and Alleanza Nazionale. The coalition that included the PDS and Rifondazione managed only to muster 34 percent.

Alleanza Nazionale had only been launched as a new party shortly before the 1994 elections. Its main component was the Italian Social Movement (MSI), the former neo-fascist party, and its leader Gianfranco Fini had been leader of the MSI. The old MSI had been marginal to Italian politics, considered heir to the old Fascist Party of Mussolini, and its vote had been around 5-6 percent in most elections. But in 1994, in its revamped image as Alleanza Nazionale, it leapt to 13.4 percent and became a component part of the first Berlusconi government.

Berlusconi's victory in alliance with the Northern League and Alleanza Nazionale gave a new impetus to lesser-evilism / Image: public domain

Berlusconi's victory in alliance with the Northern League and Alleanza Nazionale gave a new impetus to lesser-evilism / Image: public domain

This sent shockwaves through the left and there was much talk of an imminent fascist threat. Articles appeared about a new regime that would last at least 20 years. Il Manifesto newspaper (an important daily newspaper, which became the point of reference for the communist left of the PDS and Rifondazione) even went as far as to compare the rise of Berlusconi to the 1922 March on Rome that brought Mussolini's fascist regime to power.

All of this lacked any sense of proportion, and also lacked any serious analysis of what Alleanza Nazionale was. It was not a fascist party, but had become a right-wing conservative party. Fini had understood that he might be able to capture some of the right-wing voters who were abandoning the Christian Democracy, which he did successfully. In so doing, he publicly broke with the real fascists within the MSI, who went on to form a more marginal far-right party.

The mood in the country, however, was one of real fear of a far-right takeover. 25 April is the anniversary of the fall of the Mussolini regime in 1945, and is celebrated as a national holiday. Over the years, the anti-fascist demonstrations had become almost routine commemorations with small numbers participating. But this time, on 25 April 1994, a few weeks after the elections, more than 500,000 people took part in the main demonstration in Milan.

Lesser-evilism raises its head again

And here is where lesser-evilism raises its head once more. This time it was to have a direct impact on the fortunes of Rifondazione Comunista. The two main blocs in Italian politics were to become known as the “Centre-Right” and the “Centre-Left”: as if to say that the Right and the Left no longer existed! The Centre-Right was the alliance around Berlusconi. The Centre-Left was anchored around the PDS, but it also included a number of bourgeois parties.

Within a few months, the first Berlusconi government – with its attack on pensions, cuts in social spending, and the announcement of a number of privatisations – provoked a massive workers’ mobilisation, which saw spontaneous walkouts from the factories and other workplaces, culminating in one of the biggest demonstrations Italy has ever seen, on 12 November 1994, with over 1.5 million participating. Shortly afterwards, the Northern League withdrew its support for Berlusconi and in December he was forced to resign.

There were no new elections, however. The Italian ruling class resorted to what was referred to as a “technocratic government”, made up of supposedly apolitical “experts”, led by the ex-Director General of the Bank of Italy, Lamberto Dini, who had also been Berlusconi’s Treasury Minister. This government still required some kind of support in parliament and this was provided by the so-called Centre-Left, although it only had a majority in the Senate, but with the Northern League also adding its support it was able to last until the Spring of 1996. That government managed, with the agreement of the trade unions, to pass a law changing the way pensions were calculated as a means of cutting public spending. This led to a large movement against the Dini government and the growth of Rifondazione Comunista among an important layer of the working class.

In April of the same year, new elections were held where the Centre-Left stood under the name of the “Olive Tree”, a coalition made up of the PDS and several smaller bourgeois formations, such as the Popular Party (former Christian Democrats) and the Republicans. That coalition won and went on to form the next government, with Romano Prodi as Prime Minister. Prodi was a former minister and member of the Christian Democrats, and he had also been at the head of the IRI, the state enterprise board, and had overseen a number of privatisations. He was to become identified with the austerity that was to be promoted by the Centre-Left government.

Rifondazione Comunista stayed outside the Olive Tree on its own and won a respectable 8.6 percent in the 1996 elections. It had, however, made an electoral pact with the Olive Tree of where to stand and not to stand, as a means of maximising its number of MPs.

This is when the real problems began to emerge for Rifondazione Comunista. After the 1996 election, the party leaders decided to externally support the first Prodi government. The irony of this situation is that that government was able to achieve far more for the capitalist class of Italy than any of the previous governments, in terms of privatisations, casualisation of labour, cuts in social security spending and so on.

Rifondazione was under enormous pressure from the PDS and bourgeois “public opinion” to continue providing parliamentary support for the coalition government (again, to prevent a return of the right wing). The internal debates in the party were dominated by this burning question: should we continue to support Prodi’s government? The argument used to justify continued support was more or less the following: “if we make the Prodi government fall, then Berlusconi – with his fascist allies – will make a comeback”.

The Marxists in Rifondazione [gathered around the paper Falcemartello, the then-journal of the IMT in Italy] warned that not only would the party pay a heavy price for this, but Berlusconi would make a comeback precisely because of Prodi’s austerity measures. In spite of the leadership’s wavering on this question, however, pressure was building up within the ranks of the party, who were finding it more and more difficult to stomach this policy.

In October 1998, the party leadership – after having supported many similar previous laws – finally decided to withdraw support for Prodi’s budget. This provoked an important split from the party of the old leader Cossutta and his faction. Although Prodi left the scene, the Olive Tree coalition continued to govern Italy until 2001, with the majority of Rifondazione’s MPs joining the government after they had split away from the party.

2001 elections, the first warning

In the 2001 elections Rifondazione’s vote went down to 5 percent. This was the first sign of what was to come. But what was even worse was that Berlusconi made a big comeback that year, winning the elections with 367 MPs against the Olive Tree’s 248.

Using the logic of lesser-evilism – i.e. that it was better to support the centre-left, even if this meant supporting many of its austerity measures, than to allow Berlusconi and his “fascists” back in – the leadership of Rifondazione failed on all fronts, it failed to stop Berlusconi’s return, it demoralised its rank and file and it lost a significant number of its MPs. Here we see how lesser-evilism rather than strengthening the left – in the form of Rifondazione – was a key factor in its further weakening.

Entering government meant the PRC was tainted by the reactionary budgets the government brought against working people, wrecking the party's reputation / Image: Soman

Entering government meant the PRC was tainted by the reactionary budgets the government brought against working people, wrecking the party's reputation / Image: Soman

One would have thought that, by now, the party leadership would have learned a lesson, that they would have drawn the correct conclusions and made a turn to the left, abandoning all forms of class collaboration. On the contrary! Halfway through the legislature, in October 2004, the party re-joined the Centre-Left coalition in opposition, once again with Prodi as its leader.

In the 2006 general election, the PRC stood as part of the Centre-Left coalition, now known as “The Union”, which won by a narrow margin against Berlusconi’s coalition. The party received 5.8 percent of the vote and 41 MPs. Bertinotti, the leader of the party, was rewarded for his services by being elected Speaker of Parliament. As if this were not enough, the party this time actually joined the government, with Paolo Ferrero as Minister of Social Solidarity together with a number of undersecretaries.

As part of the coalition government, the party was now called on to vote in favour of the budgets, but it went even further than that with Rifondazione MPs voting to refinance Italy’s military operations in Afghanistan and to send troops to Lebanon. All this left a sour taste in the mouths of many who had voted for the party. Eventually, Prodi’s majority fragmented, the government fell in January 2008 and elections were called for April.

The leadership of Rifondazione this time went into the elections in a Left coalition called the Rainbow Left, which included the group that had split to the right of the party a few years earlier, as well as the Greens. The combined vote of the four formations that made up the Rainbow Left had been 10 percent in the previous elections. This time they won a mere 3.1 percent and no MPs, an unmitigated disaster!

After the election defeat an extraordinary party congress was called. The majority of the leadership promoted the idea of liquidating the party into a “broader” formation, but failed to gain an absolute majority. The 2008 congress represented the last possibility of making a clear turn to the left in the party’s policies, but the expectations around the left turn were soon to be frustrated. The party suffered another split to the right, promoted by the then-leader Bertinotti and Niki Vendola.

Since then the leaders of Rifondazione have been desperately seeking ways of getting back into parliament. In 2013, in yet another alliance on the left, Civil Revolution, things went even worse, with the joint list winning only 2.2 percent and yet again no MPs. This was followed in the 2018 general election, when Rifondazione stood as part of the Power to the People electoral list, which won a miserable 1.1 percent of the vote and no seats.

The final chapter

This was the final chapter in the inglorious “lesser-evilism” – Italian style! Not only had that idea failed to stop Berlusconi, who governed Italy yet again between 2008 and 2011, but it destroyed Rifondazione in the process. At the time of the split in the old Communist Party between Rifondazione and the PDS back in 1991, the party had 112,000 members (reaching a peak of over 130,000 in 1997) but has now been reduced to less than 10,000 on paper, with its active base far smaller than that.

As of July 2019, however, according to figures released by the National Committee, the “certified”, i.e. verified, members were 5,178 in 2017 and 2,191 in 2018, which if confirmed would mean that what was once a significant force on the left with more than 40 MPs, has now been reduced to an insignificant sect eking out an existence on the margins of Italian politics.

They wouldn’t listen when the Marxist wing of the party was hammering away with the idea that the party should not support the Centre-Left, as this meant supporting all the anti-working-class policies that those governments pushed through. They would not listen when we explained that, if the party continued down that road, far from stopping Berlusconi they would help to prepare the conditions for his return with even more votes. That is precisely what happened, and more than once.

In Italy lesser-evilism destroyed the left and has put the working class in a position of having no party that it can call its own. The right in Italy has managed to transmit a message to a significant section of the electorate that “la Sinistra” [the Left] defends bankers and businesspeople, cuts pensions and imposes austerity. This is not difficult to do, considering the number of Centre-Left governments we have seen in the past 20 years or so, all of which have carried out draconian austerity.

Another important element in this equation is the question of fascism and whether it is a real threat in Italy today. The error started when the old MSI metamorphosed into Alleanza Nazionale, and when this then emerged as a member of Berlusconi’s first coalition government in 1994. The mistake was to believe that a Fascist regime could come to power.

It is now 26 years since the first Berlusconi government, and we still don’t see a fascist regime coming any day soon. When Mussolini set up his party in 1919, it would be in power just three years later. But that was because the working class had already suffered a major defeat in 1920. Furthermore, the social base of fascism was far stronger than it is today.

The balance of class forces today – where the peasantry, small shopkeepers and petit-bourgeois in general, have been reduced to a minority in society – do not permit for the creation of a mass fascist force capable of destroying the organisations of the working class. That does not mean that small fascist organisations are not a danger to the labour movement, in that they can carry out physical attacks on individual militants, but they cannot become a mass social force as in the days of Mussolini.

Salvini, the leader of the Lega [the old Northern League which has recycled itself as a national party] uses racist and bigoted rhetoric, but he is not in a position to launch a mass movement. The experience of Greece should be studied. The Golden Dawn was also presented as a symptom of rising fascist reaction. Where is it today? The Greek bourgeois, far from using the leaders of the Golden Dawn, had them arrested, fearing the radicalisation of the working class and youth after the assassination of the musician Pavlos Fyssas. This was not out of any progressive thinking on their part – their own history amply demonstrates that they would have no qualms in adopting repressive measures. But given the traditions and the strength of the Greek working class, they felt that the Golden Dawn, if allowed to continue with its provocations, could unleash a massive backlash on the part of the workers. So they used the reformist leaders of SYRIZA to govern the situation, i.e. the recognised leaders of the working class, as these had the authority to hold back the workers and youth. And, having used and partially discredited them, they worked to bring back their trusted New Democracy.

Had the leaders of Rifondazione had a Marxist understanding of the situation, they would not have made the blunders they did. They would have understood that, as far back as 1994, it was necessary to resist the pressures of bourgeois public opinion, “go against the stream” and maintain an independent position. Had they done so, they would have later reaped the benefits massively. But they were incapable of having a longer view of the process. They were blinded by the immediate situation and could not see what the effects of their collaborationist policies would have on the fortunes of the party.

Lesser-evilism and class collaboration flow directly from the fact that these reformist leaders can only see change in terms of what is possible within the capitalist system and within the arithmetics of parliamentary politics. They are incapable of acting in such a way that can mobilise the millions of workers and youth in their workplaces, and in their neighbourhoods. This applies not only to the right reformists but also to the left reformists.

Lessons for the United States

This experience has a bearing on events in the United States today. The left in the United States, as we have seen, is debating what approach to have towards Biden, whether he should be supported or not. Bernie Sanders has thrown his full weight behind Biden.

In a recent speech in Lebanon, New Hampshire, Sanders fully backed Biden, sowing illusions that he will defend working class Americans. Here is some of what he said:

“When three people own more wealth than the bottom half of this country; three people; that is not acceptable. Under Joe Biden and under a Democratic Congress, we’re going to change all of that. (…) there is also no question that the economic proposals that Joe Biden is supporting are strong, and will go a long, long way to improving life for working families. (…) There’s something else that Joe understands. And that is that in the midst of the worst economic crisis in our lifetimes, we need to create millions and millions of good-paying union jobs.”

The Italian experience offers a stern warning to the US left today, facing the 2020 Trump vs. Biden election / Image: public domain

The Italian experience offers a stern warning to the US left today, facing the 2020 Trump vs. Biden election / Image: public domain

What we must ask ourselves is: what kind of programme is Biden really going to carry out if he gets elected? Simply to ask the question will bring out the right answer! Biden, as we have explained, is the preferred candidate of the US establishment, and therefore, once in office, he will carry out the interests of the US ruling class; he will attack the living standards of the working class. He doesn’t even make an effort to hide the policies he’s committing to once elected.

And what needs to be hammered home is that anyone who has supported him will inevitably be tainted with those policies. Therefore, although the “lesser evil” may seem an attractive option in the short-term, it doesn’t help advance the building of a third, working-class based, force in the United States, which is what the American workers desperately need.

Furthermore, if the left is tainted with the policies of Biden, then Trump, or someone like him or even worse, will come back at a later stage. Voting for the lesser evil does not stop the “greater evil”, it merely prepares the ground to strengthen it at a later stage.

In Italy, lesser-evilism destroyed the once powerful Communist Party. How can it help to advance the US working class towards its own independent voice? We study experiences such as that outlined in this article, not out of academic interest, but because it will help us avoid unnecessary errors in the future.