The Russian Revolution took place during World War One: war and peace were critical issues. The overthrow of the Tsar and the establishment of a democratic government in February 1917 were regarded by the Provisional Government, and by the SR and Menshevik majority in the Petrograd Soviet, as a justification for continuing the support of the war effort in the name of the defence of the revolution.

Part one | part two | part four | part five | part six

In practice, this meant defence of the bourgeoisie, since they were the class most empowered by the first Revolution in 1917. The Bolshevik Party insisted that war must end and peace must be achieved on the basis of no annexations or indemnities. Most Bolsheviks supported this. However, there were some in the party, notably Kamenev, who openly espoused the need for continuing the war on the basis of defending the revolution. Lenin opposed this position in his April Theses, recognising that the masses were desperate to see an end to war. He further argued that the position of revolutionary defencism within a bourgeois state was a confidence trick upon the workers and pandering to patriotism and jingoism. From April to October, the Bolsheviks maintained that a Bolshevik revolution, the ending of the war with a democratic peace and proletarian revolution in Europe, were all parts of a single process and in practice inseparable.

Internationalism and revolutionary war

The Bolshevik Party tradition was unreservedly internationalist in outlook. It believed that nationalism was part and parcel of the capitalist system and that wars were an inevitable consequence of that nationalism. They also took seriously the original Marxist international slogan, “workers of the worlds unite, you have nothing to lose but your chains”. In addition, the Bolsheviks were also strongly of the view that a Russian socialist revolution could not be sustained without one or more advanced capitalist countries also becoming socialist and linking up with the Russian proletariat.

Lenin opposed a 'revolutionary war', but was in a minority within the party leadership / Image: public domain

Lenin opposed a 'revolutionary war', but was in a minority within the party leadership / Image: public domain

Bolsheviks believed that the ending of capitalism and landlordism in Russia would raise the morale of workers and peasants and make them stronger than any opponent. This new class war would rouse the masses internationally. This position was crucial to understanding why the party adopted various positions over the peace negotiations and the issue of revolutionary war. After the establishment of a workers’ and peasants’ state Lenin was not, in principle, against waging a revolutionary war against the imperialist powers but, looking at concrete reality, he understood the masses did not want to fight, even for a workers’ state, at this stage. In any event, the fledgling state had insufficient resources to wage a war of any kind and by December 1917 was faced with civil war. Therefore, Lenin implacably opposed a revolutionary war at this stage. But a majority in the party leadership did not. This set the scene for a prolonged and, in the end, damaging struggle within the Bolshevik Party, which was only finally settled in March 1918.

The peace decree and the armistice with Germany

One of the very first decrees, issued a day after the October Revolution, by the new government was on peace. It called upon all belligerent countries to halt the war immediately on the basis of a just and democratic peace with no annexations or indemnities, and to allow all nations the right of self-determination on a free vote. At the same time, the decree abolished secret diplomacy, calling for open and transparent negotiations, and annulled all secret treaties agreed by the old regime, stating that such secret treaties would be published. Finally, the government called for an immediate armistice.

A temporary armistice between Russia, Germany and her allies was agreed on 2 December 1917 / Image: public domain

A temporary armistice between Russia, Germany and her allies was agreed on 2 December 1917 / Image: public domain

After initial negotiations between the Soviet delegation and those of Germany and her allies, an armistice was agreed on 2 December. It allowed 28 days before full peace negotiations took place. It was agreed to maintain current military positions, and further agreed that Germany would not send troops to the western front because of the armistice and would allow a degree of fraternisation between troops.

Trotsky, after some resistance on his part, was appointed Commissar for Foreign Affairs and would eventually lead all negotiations, which were to take place in Brest-Litovsk: a small town on the Russian-Polish border, now in Belarus.

Foreign policy, under Trotsky, comprised largely of appeals to workers and revolutionary groups throughout the world to organise a world revolution. He paid scant attention to the traditional role of a Foreign Secretary, saying, “My job is to publish the treaties, issue some revolutionary proclamations and shut up shop”. Former secret treaties were quickly published, ambassadors recalled and new ones sent out. Money was made available for international revolutionary organisations. Agitational newspapers were published, aimed at foreign workers and prisoners of war. For their part, foreign governments rebuffed Russian attempts to obtain friendly responses and all countries opposed any rapprochement with the Bolsheviks. However, there were contacts between Russia and foreign ambassadors and initially the allies hoped to persuade Russia to continue fighting Germany. When this failed, their opposition to Bolshevik Russia noticeably stepped up.

Negotiations at Brest-Litovsk and Bolshevik splits

Following the armistice agreement, negotiations re-started at Brest-Litovsk, with Joffe initially leading the Russian delegation. These discussions were inconclusive. The Soviet delegation put forward their positions on annexations and the rights of nationalities to enjoy political freedom and ending colonies. The Central Powers (Germany, Austro-Hungary, Turkey and Bulgaria), led effectively by the German General Hoffman, played lip service to these demands as they had no intention of giving up Poland or those Baltic states under their control. Moreover, they now included in their delegation representatives of the Ukrainian Rada (a nationalist-led parliament), weakening the Soviet claim to represent all Russian territories. The Red offensive against the armed nationalists in Ukraine was only just underway.

Trotsky took over as leader of the Soviet delegation to the peace negotiations at Brest-Litovsk in 1918 / Image: public domain

Trotsky took over as leader of the Soviet delegation to the peace negotiations at Brest-Litovsk in 1918 / Image: public domain

Trotsky took over as leader of the Soviet delegation in the New Year, and hoping that delaying tactics would work in their favour, used the negotiations as a platform for propaganda. There were definite signs of revolt among workers in Austria and Germany and among their soldiers and sailors. Strikes occurred in Austria in mid-January and later in the month there were serious strikes in Berlin, Hamburg, Danzig and Kiel. Eventually, the Central Powers sought to break the deadlock by stating their demands for the Soviets to cede all territory currently occupied by Germany in the North and to negotiate the southern boundaries with the Ukrainian Rada. Trotsky decided that he now needed to return to Petrograd to discuss with the leadership the best response. There then began a series of debates and votes. In the first meeting, 63 leading Bolsheviks debated the issue of peace. Lenin argued for taking peace at any price to secure the bridgehead of the revolution and wait for better times. Despite Lenin’s prestige, he got only 15 votes. 32 votes, mainly Moscow Bolsheviks led by Bukharin, were for a revolutionary war against Germany and her allies rather than accepting their terms. Trotsky took a third position of neither war nor peace but to continue to delay the proceedings as long as possible in the hope revolution would break out in Germany of Austria and if necessary declare peace unilaterally when pressed. He got 16 votes.

A few days later the Central Committee of the party met and Lenin again called for immediate peace. Only Stalin was clear in his support so Lenin agreed to Trotsky’s delaying position and this passed 12-1. Only two, Bukharin and Dzerzhinsky, supported pursuing a revolutionary war.

Trotsky returned to the negotiations later in January, but after spinning it out as long as possible he made a unilateral declaration to end the war. He then walked out of the talks. Seven days later the German High Command announced it was going to resume hostilities. The Bolshevik unilateral declaration of peace was intended as a signal to all workers and soldiers involved in the war to rise up and oppose their leaders and join the struggle. This did not occur and the Central Powers immediately renewed hostilities. Meeting little resistance, they quickly advanced on all fronts.

Meanwhile, the Bolshevik Central Committee was in almost continuous session. Lenin again called for seeking terms with the Germans, but got only 4 votes against 6, with Trotsky voting against. Lenin then posed the question: what if the German army advanced and there was no revolution in Germany and Austria? By 6-1, with 4 abstentions (Trotsky went over to Lenin) it was agreed that, in that event, peace should be made. But the Germans were already advancing. The issue was debated the following day. Despite some movements, the vote for Trotsky’s hesitation again carried 6-5. But by evening it was clear the German advance was strong and Russia was threatened. At this point Trotsky went over to Lenin and the Central Committee agreed to ask for peace negotiations by 7-5. Other party and Soviet bodies rapidly ratified this decision, although not without division, and a telegram was sent off agreeing to a renewal of the peace negotiations.

The final Brest-Litovsk Treaty and its ratification

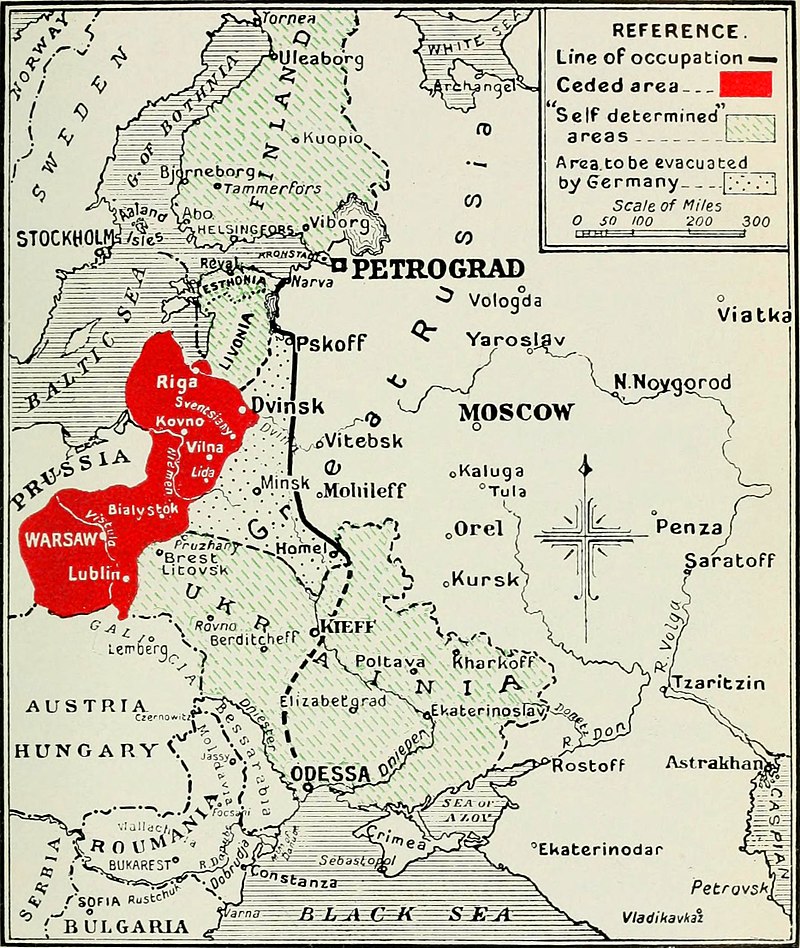

However, Germany was in no hurry to accept and took full advantage of its position, advancing deep into the Ukraine and other areas. Eventually, the Germans came up with new, much harsher terms than before: Soviet withdrawal from Ukraine, Lithuania, Estonia and Finland and the ceding of territory to Turkey in the south. The treaty also demanded Soviet recognition of the Ukrainian Nationalist Government or Rada. The implications of the Treaty for the economy of Soviet Russia were immense. They lost some of the most productive areas of Russia, especially in the Ukraine with its large assets in coal, industry and agriculture. In all they lost 40 percent of industrial capacity, 45 percent of fuel, 90 percent of sugar, 70 percent of the metal industry and 55 percent of wheat potential. The demand to withdraw the Red Guards from Finland led to a German-backed counter-revolution of considerable ferocity.

So harsh were these terms that many leading Bolsheviks, especially in the Moscow Region, again resisted acceptance and ratification. There followed another heated debate in the Bolshevik Central Committee. Lenin moved acceptance, this time saying he would resign if he didn’t gain the vote. Trotsky opposed but, in the end, abstained, as did Dzerzhinsky, Joffe, and Krestinsky, giving Lenin a 7-4 majority. In early March, the Soviet Government signed the new terms of Brest-Litovsk. Full internal ratification had to go through various bodies and the debates raged on. At the Seventh Bolshevik Party Congress in March 1918, Trotsky again reiterated his opposition to accepting such harsh terms but declared he would not vote against Lenin. This was then carried by 28 votes to 9. At the all-Russian Central Executive Committee, after a speech by Lenin it was carried 116 votes to 84. On 16 March, the All Russian Congress of Soviets, after two days of stormy debate, ratified the government’s decision by 784-262.

The Germans demanded Soviet withdrawal from Ukraine, Lithuania, Estonia and Finland, ceding of territory to Turkey in the south and recognition of the Ukrainian Nationalist Government or Rada / Image: public domain

The Germans demanded Soviet withdrawal from Ukraine, Lithuania, Estonia and Finland, ceding of territory to Turkey in the south and recognition of the Ukrainian Nationalist Government or Rada / Image: public domain

These details are recounted to illustrate the tradition of debate and internal democracy within the Bolshevik Party and Soviet Russia at this time. This tradition, although necessarily curbed in the acute conditions of Civil War later in 1918, nevertheless remained at the heart of the Bolshevik Party as long as Lenin and Trotsky remained at the helm. It is instructive, in view of the later cult of the personality around Stalin, that Lenin, despite his immense standing in the party and among the workers, was consistently opposed by many leading comrades throughout this process. When he was defeated he accepted it and fought on with unflinching argument in meetings and in writing.

In fact, a notable feature of Lenin throughout is that at every stage and moment of the Revolution he was not only driving the process in practice, with attention to every detail, but also writing articles, resolutions and even longer works. It is true that, in the final stages of the debates on Brest-Litovsk, Lenin threatened to resign if his views were not accepted, but this was after months of exhaustive debate and at a critical moment for the survival of the revolution. Lenin always considered it vital, at this stage of world developments, to keep the core of the revolution secure.

The left wing of the party, around Bukharin, openly stated that they were prepared for a split in the party and were willing to sacrifice the revolution on the altar of an international revolutionary war. Lenin considered this absurd posturing and wrote a biting critique in February 1918, called “Strange and Monstrous.” In this piece Lenin shows how the process of debate within the party was carried out. He vigorously defends the left-wing’s right to express its view:

“It is quite natural that comrades who sharply disagree with the Central Committee over the question of a separate peace should sharply condemn the Central Committee and express their conviction that a split is inevitable. All that is the most legitimate right of party members, which is quite understandable.”

But, he did not fail to condemn their reasoning as “strange and monstrous”, nor hesitate to call them out for revolutionary phrasemaking. Immediately after the conclusion of this drawn out process of Peace he wrote a substantial text on the broader issues it raised and called it, Left-Wing Childishness and Petty-Bourgeois Mentality. He was to return to this theme two years later in 1920 when he wrote Left-Wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder.

Soviet foreign policy in 1918

Before returning to the immediate issues at home it is worth noting another issue that split the Bolsheviks at this stage and it again illustrates the division between the realists and what Lenin called a petty-bourgeois mentality. This occurred over the approach the Soviet Government should take in confronting the capitalist powers.

The left wing around Bukharin, stated that they were prepared for a split in the party over the question of revolutionary war / Image: public domain

The left wing around Bukharin, stated that they were prepared for a split in the party over the question of revolutionary war / Image: public domain

The notion widely held at one time, that a workers’ government would have no truck with any capitalist power, proved untenable and unrealistic. The capitalist states were not a uniform bloc and divisions could be exploited. The leftists, led by Bukharin, refused to contemplate any deals with the capitalists. Lenin and Trotsky tended to operate on the pragmatic and realistic side, although, as we have seen, Trotsky sometimes took longer to reach the same conclusions as Lenin. Occasionally, it was the other way around, with Lenin acknowledging that Trotsky had been correct. In the Central Committee in February 1918, Trotsky argued in favour of accepting arms from any country, even capitalist ones, on the one condition that no political obligations were given to these countries in return. This was hotly debated and only carried 6-5 with Lenin not attending but supporting the proposal. In the end, this proposal was without effect because the vague offers of support from USA, Britain and France were predicated on keeping Russia in the war so as to keep Germany pinned down in the east. Once the Brest-Litovsk Treaty was finally signed the other imperialist powers declined Russia any assistance.

In the wake of the Brest-Litovsk Treaty a dual, inter-meshed foreign policy emerged: to promote world socialist revolution and defend the national security of the Soviet Republic. This would last as a consistent and integrated approach throughout the civil war and until the fight against the aggression of the allied powers finally ended in early 1921. Stalin later tried to portray a split between Lenin and Trotsky over the issue of world revolution or socialism in one country. In fact, this is entirely false and distorts the real split, which was between Lenin and the left communists that included Bukharin, Radek and Uritsky.

Lenin, like Trotsky, remained a powerful advocate of world revolution and indeed frequently said that it was the only hope for the long-term success of the Russian Revolution. Lenin said that if necessary he would be in favour of sacrificing the Russian Revolution for a German Revolution, if it occurred, which would be on a much higher level and would hasten world revolution. The difference between Lenin and Trotsky was essentially one of balance. Trotsky was slower than Lenin to realise that the German Revolution would take time to mature, over-estimating the prospects for revolution.

Early struggles on the periphery

The general headquarters of the Russian Army, a veritable citadel in a time of all-out war, was situated away from Moscow and Petrograd. Here the Bolsheviks were weak. The soldiers’ Committee of the Armies, which had been elected at the beginning of the February revolution, was controlled by the SRs and had a cosy relationship with the generals. Six days after the October Revolution, they decided to oppose the Bolsheviks and march on Petrograd. But the mood of the soldiers, who welcomed the revolution, prevented this. When Lenin then called on the soldiers to elect new delegates and organise for an armistice with Germany, the old army establishment was doomed. These elections were held on 18 November. Following these elections, General Dukhonin, the supreme army head, who had defied the Bolshevik Government’s orders, was arrested and executed.

From October to March, the strong tide in favour of the Bolshevik-led Soviet Government had swept most urban and working-class areas of Russia. Even in the strongly nationalist areas of the Ukraine, parts of the Caucasus and the Don region, Red forces had been triumphant. Local soviets had sprung up everywhere. Most of the troops were with the Bolsheviks and the peasantry were broadly supportive as they saw their land needs being addressed. But from that point on the situation for the government became more and more difficult. The ending of the First World War proved a key factor in the west, as German troops occupied so much of the land that was highly productive for all parts of the economy. The Germans and their allies were keen to weaken Russia as far as possible and also to undermine Bolshevism by arming and encouraging nationalists and elements of the old order in Russia, principally the old Tsarist generals and officers, so that they could mount an effective counter-revolution. This, in effect, was the start of three years of brutal civil war.

Anti-Bolshevik, White forces in Russia, 1918 / Image: public domain

Anti-Bolshevik, White forces in Russia, 1918 / Image: public domain

A number of generals and officers of the Imperial Army fled south to the Ukraine, where the Government was nationalistic and anti-Bolshevik. An Army of Volunteers, as the first White force was called, led by General Kornilov, gathered in the south, with more officers than men. Ukrainian nationalism, infused with certain elements of socialism, attempted a form of self-government under the old parliament, called the Rada. Eventually, struggles broke out between Bolshevik supporters in Kiev and the nationalists; the Reds took Kiev in January. Ukraine fell largely under Bolshevik control by February 1918.

After November there was a general strike in Finland. This was largely victorious but there was no revolutionary workers’ party prepared to take power. So, the workers took matters into their own hands and took power in Helsinki, driving out the bourgeois government. Still, the social democrat leaders failed to drive through a revolution and opted for radical but piecemeal change. The Russian Government passed a decree giving independence to Finland at the end of 1917. Momentum gathered in 1918 and by February a new constitution was established providing for an elected assembly every three years along with other highly advanced features.

The Finnish social democracy attempted the highest ever form of bourgeois democracy. But, in the circumstances, it was utopian and met with fierce armed reaction. The bourgeois launched a White terror, using a battalion of Finns in the German army. Red Guards and soviet supporters flocked to support the working class. Soviet forces had to withdraw under the terms of the Brest Litovsk Treaty. Vicious fighting then led to extreme white terror and the defeat of the Red forces. Up to a quarter of the proletariat were subsequently killed and murdered (100,000).

The Caucasus area was complex with many nationalities and conditions. This proved a difficult area for the pro-Bolshevik, revolutionary Red forces who were initially defeated by a combination of so-called socialist Georgians and reactionary Turks and Tartars.

In the Don region, another complex war occurred, involving several old imperial generals, complicated by divisions within the Cossacks population. The Cossack cavalry had traditionally been used by the Tsarist regime as a force for reaction. When the October Revolution, occurred the Don Cossack Council declared independence. General Kaledin welcomed former officers and some soldiers from the old imperial army and thus began the formation of a White army that was to play a lasting role in the ensuing civil war.

In December 1917, the Soviet government sent a Red Guard force to assert Soviet control. At this stage, the White forces were ill-equipped, poorly organised and unable to resist the Red forces. As a result, the Don Cossack Council agreed to yield to the Soviet forces, causing General Kaledin to commit suicide. The tide turned in May 1918 due to the German invasion in the west and the growth of the White forces under Generals Kornilov and Alekseev. The Cossack leadership rebelled against the Soviet administration and, with the improved White forces, armed and supplied by the French and British, were able to defeat most Red forces and resume control over large areas. In the process, there were many massacres and atrocities against Bolsheviks and the working class generally.

In Siberia and in the Central Asia regions Bolsheviks also achieved early success in the main centres, only to suffer reversals at a later stage.

The White Forces

The White movement and its armies were so-called because the colour white was associated with the Tsar. They represented the old defeated classes of the monarchy and the bourgeoisie. The movement, as such, did not have a strong social base. It drew in various elements dissatisfied with the Bolshevik regime, usually reactionary nationalist elements. Few wanted to see the Tsar restored, except the leaders and especially the army leaders, who became, in effect, petty dictators.

The Red Army, under Trotsky, achieved a strong, centralised leadership and had a clear purpose of defending the revolution / Image: public domain

The Red Army, under Trotsky, achieved a strong, centralised leadership and had a clear purpose of defending the revolution / Image: public domain

In general, the White leadership was against separate national states and desired a return to a united empire. There was also a strong current of antisemitism within the White armies. Western sponsors expressed dismay at this, especially as the Bolsheviks had prohibited antisemitism and appeared more progressive. Winston Churchill personally warned General Denikin, whose forces effected pogroms against the Jews, that “my task in winning support in Parliament for the Russian Nationalist cause will be infinitely harder if well-authenticated complaints continue to be received from Jews in the zone of the Volunteer Armies”.

One of the abiding weaknesses of the White forces was their lack of unity. The leaders squabbled and there were many who joined the umbrella of the Whites simply because they opposed the Bolsheviks, rather than having a united vision of what they wanted. Ultimately, this played into the hands of the Red Army, which, under Trotsky's command, achieved a strong, centralised leadership, and, of course, always with the clear purpose of defending the revolution.