The last few months of 1918 were no less tumultuous than the earlier part of the year. The civil war dominated all aspects of life, intensifying on several fronts. The pressures of counter-revolution at home also increased, with attempted assassinations of leading Bolsheviks and countless plots by Cadets, SRs, Anarchists and Mensheviks.

Part one | part two | part three | part four | part six

The Entente powers – Britain, France, the USA and others – moved from indirect interventions to direct invasions of Russian territory. All efforts to create a socialist economy and administration were severely hampered by war, famine and dislocation. The response of the Soviet regime was to assume greater central powers economically, socially and politically; and also to combat terror with some degree of repression. This phase has become known as War Communism. The end of the First World War in November 1918 marked a significant change in the situation, leading to greater hopes for a German socialist revolution and the ability to re-take some lost territory. However, the imperial powers also felt able to increase their efforts to topple the Bolsheviks.

War Communism

The series of sharp crises that beset the Soviet government from April 1918 onwards forced a change of direction in terms of centralised control and draconian measures. In large part, this was a necessity borne out of war: both the imperialist world war and the ongoing and intensifying civil war.

All countries that have been engaged in war in the modern era have been forced to adopt measures of control, direction and requisition. Russia in the spring and summer of 1918 was no exception. It was suffering unparalleled difficulties in terms of access to resources – especially food – a chaotic and disrupted distribution system, declining production and the increasing demands of mounting a full-scale military response to a counter-revolution backed by foreign imperialism. In addition, the international blockade imposed on Russia prevented normal trade and the ability to obtain resources from abroad. All these factors led to a series of new measures in the late spring, summer and autumn of 1918 that continued until after the civil war. Collectively, these measures have been dubbed “War Communism”.

The basic outline of war communism started in late March with the ending of workers’ control of the state railways and the adoption of strong centralised and disciplined management. This was followed in April 1918 with the nationalisation of external trade: a direct response to the international trade blockade. Also in April, compulsory military training was instituted for all (working-class) men between the ages of 16 and 40. In May, a decree was passed abolishing the right of inheritance. Assets worth over 10,000 roubles would revert to the state on one’s death. In June, measures to forcibly requisition grain from rich peasants were instituted. Among the steps taken was the formation of Committees of Poor Peasants, which were to assist Food Brigades sent from the urban areas to identify and seize grain stocks, by force if necessary. Many severe battles took place in the process of implementing this policy.

The crises from April onwards forced centralised control and draconian measures: "War Communism" / Image: public domain

The crises from April onwards forced centralised control and draconian measures: "War Communism" / Image: public domain

Under a decree passed in April, consumers’ cooperatives were given a central role in economic life and allowed a degree of independence. In June this was curtailed through a series of measures designed to bring this sector firmly within the control and direction of the Supreme Economic Council and its lower tier structures. In May, the sugar industry was nationalised and later, in June, a decree was passed allowing for the nationalisation of all big industry. This was implemented gradually over the summer months. The ability to manage such nationalised industries posed a major problem and eventually involved hiring several old managers and supervisors, a policy not without opposition from within the party.

Whilst for Lenin and Trotsky, and the majority leadership of the Bolsheviks, War Communism had become a necessity and likely to be temporary, for the left communists it was the programme for which they had been arguing for some time. They saw it as the long-term solution to establishing socialism in the Soviet Union and a vindication of their position. Many left communists decided they could no longer sustain the faction and it petered out in the autumn of 1918. War Communism continued through the long years of the civil war, finally being superseded by the New Economic Plan of 1921.

The civil war

The changing fortunes and sheer scope of the civil war are complex. While the details are not uninteresting they are beyond the scope of this article to describe. Suffice it to say that the war was a highly mobile one that did not involve huge armies in any one place, but overall embraced hundreds-of-thousands of Red and White forces (as well as the latter’s allied imperialist forces). It was also extremely brutal and many lives were lost, although famine accounted for even more deaths.

By the summer and autumn of 1918, the Soviet regime was beset on all sides by hostile forces. In the north, British, French and allied forces linked up with local reactionary groups to occupy parts of Russia around Murmansk and Archangel. In the west, the Germans occupied the Ukraine, White Russia, Finland and the Baltic States as well as threatening Petrograd. To the south, another extended military front stretched from the southern Ukraine into the Caucasus and thence the Don region. The French, British, Rumanian and other countries were involved in this region. In the east, the Japanese, USA and others held an enclave around Vladivostok and sought linkages with other fronts further west in the Urals that had been prompted by the success of the Czech Legion along the Trans-Siberian railway.

The threat of counter-revolutionary terrorism and Red Terror

The shooting of Lenin and Uritsky and the plan to assassinate Trotsky led to a sharp reaction from the Soviet government in the form of a decree on 5 September 1918 organising a period of Red Terror. This decision was predicated on the understanding that the August attacks had been coordinated and planned as part of a wider, de-stabilising effort by imperialist and counter-revolutionary forces. Certainly the French and the British had been involved in these plots and Bruce Lockhart, a British agent, was arrested. The decree was uncompromising and called for “an end to this clemency and slackness”. It went on to call for the immediate arrests of all known Right SRs and for large numbers of hostages to be seized from the ranks of the bourgeois. At the least sign of White resistance or activity, mass shootings were to be the rule.

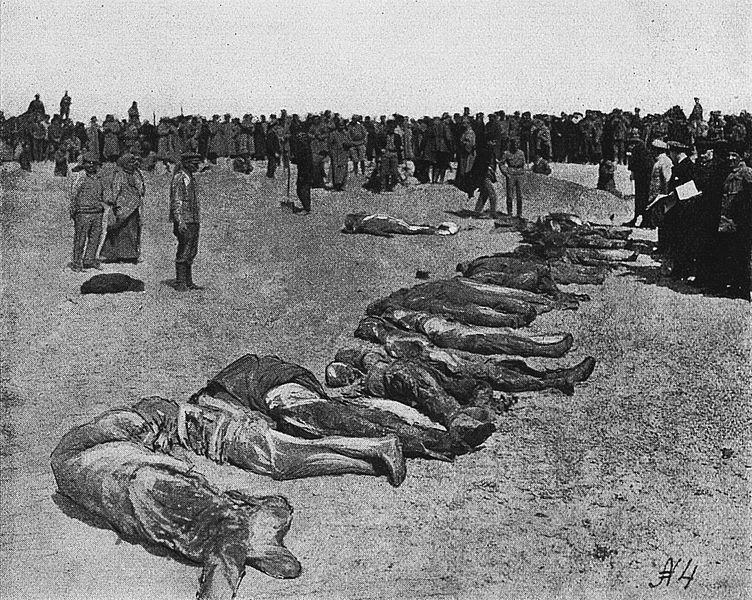

The shooting of Lenin and Uritsky and the plan to assassinate Trotsky led to a sharp reaction from the Soviet government in the form of a period of Red Terror / Image: public domain

The shooting of Lenin and Uritsky and the plan to assassinate Trotsky led to a sharp reaction from the Soviet government in the form of a period of Red Terror / Image: public domain

These measures were carried out in all Soviet-held areas. Over 500 counter-revolutionaries were shot in Petrograd and many grand dukes, officers, industrialists, bankers arrested as hostages. At Krondstadt, a further 500 were shot. Elsewhere, there was a much-lower level of shooting. Although the Red Terror slackened off it did not cease, largely because the White Guards and their allies, the bourgeoisie in the towns and cities, continued to plot, plan and fight for counter-revolution. In a sense this was a heightened internal class war, in much the same way as the raging military battles being fought all around Russia. Victor Serge pointed out that, in the first six months of 1918, the Cheka executed only 22 people. In the last six months, in response to the growing threat, there were more than 6,000 executions covering both counter-revolutionary activity and criminal offences. This represents a considerable increase but in the grand scheme of things, and set beside the untold thousands of workers and peasants killed by the White forces in numerous massacres and atrocities, it is possible to see it, within a war environment, as commensurate.

Crisis on the Eastern front

The loss of Kazan to Czechs and other anti-Bolshevik forces in August sent alarm bells ringing in the Kremlin. The counter-revolution now threatened the heartlands of Russia. The area between Kazan and Moscow was relatively open and not easy to defend. The Red forces under Vatsetsis, the Commander of the eastern front, had been routed. Vatsetsis gathered those who remained at Sviazhsk (a small town, 40 miles west of Kazan on the Volga) and dug in.

Trotsky rushed to the scene with 200 hand-picked communists in an armoured train, later to become one of the enduring symbols of the civil war. He set up his headquarters at the railway station in Sviazhsk and set about galvanising Red forces with a blend of intensive propaganda and iron discipline. He also brought in fresh troops and supplies by rail, overcoming the numerous attempts at sabotage by railway workers along the route. His train carriage became the hub of organisation and discipline. Trotsky led by example, taking part in a daring raid on the White fleet of ships on the Volga, setting them all ablaze and thus setting the basis for the re-taking of Kazan by 10 September. This was clearly a turning point on the eastern front and secured the heartland of Russia. The Red forces were now able to take the offensive. Simbirsk was re-taken on 12 September under the leadership of brilliant new Commander of the First Army, Tukhachevsky. The Samara government was now in disarray. On 3 October, Syzran was re-occupied and on the 8th, Samara itself fell. The Samara government retreated east of the Urals to Ufa and was then swept out of existence by a coup from Admiral Kolchak in Omsk in November. The Red Army maintained a steady advance on this front, taking various towns and areas to the east until the end of 1918.

The capture of the Volga region was not just an important psychological victory, it gave access to some good, grain-yielding areas and the important Volga transport system. Trotsky had shown himself to be a brilliant organiser and strategist as well as an inspiration to the troops. After these successes, he returned to Moscow and set about reorganising the Supreme War Council into the Revolutionary War Council with powers to decide matters of military policy. Under it, he established Revolutionary Councils of War for each of the 14 armies, each council consisting of the commander of the army and two or three commissars. On the War Council, Trotsky included many of the key figures who had shown special merit in the Urals and Volga campaigns.

The Southern Front and early clashes between Trotsky and Stalin

Following their defeat in the Volga and the Urals, the Whites had their main strength in the Cossack country of the Don in the south, led by General Krasnov, who had been foolishly released by the Bolsheviks after his failed attack on Petrograd shortly after the revolution. With the support of the Germans, Krasnov established a quasi-autocratic Government of the Don. Further south in the Kuban, another Cossack area, the leader was General Denikin, who was bitterly opposed to Krasnov. Divisions within the White forces were an abiding feature of the war and proved to be one of the critical factors in the outcome.

The Bolsheviks had been defeated in the main Don city of Rostock and in other towns. There were roving bands of red partisans but no significant force within the region itself. Reprisals and brutality against workers who supported Bolsheviks were extreme. The southern front lay broadly to the north of the Don region, abutting the Volga region. Here, the chief Red commander was Voroshilov, who led the Tenth Army, and whilst bravely resisting the advance north of Krasnov, resisted instituting the changes that Trotsky sought in the organisation and discipline of the Red Army. There is no doubt that the situation in the south was complicated. The Cossacks were strongly divided between rich and poor, the rich favouring the Whites, the poor the Reds. Often villages took different sides.

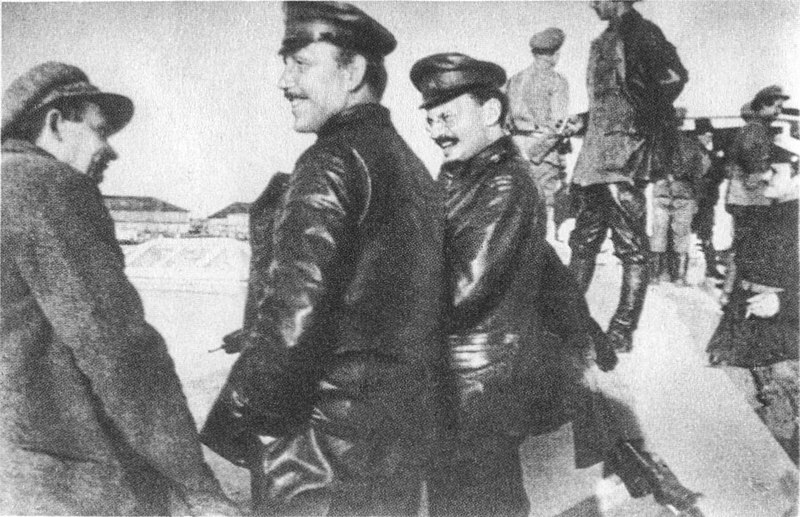

The machinations of Stalin and the Tsaritsyn group against Trotsky anticipated the conflict to come / Image: public domain

The machinations of Stalin and the Tsaritsyn group against Trotsky anticipated the conflict to come / Image: public domain

There were many separate bands of Red partisans and a culture of guerrilla warfare rather than the centralised, organised approach that Trotsky sought. Voroshilov’s resistance to Trotsky’s reforms received backing from Stalin, who was in the areas organising grain requisitions. Later in September, Stalin acted as the chief political commissar for the whole southern front, leading to constant friction between the front and the army headquarters in Moscow. In order to resolve the situation, Trotsky took strong action that clearly marked a step in the developing antagonism between Stalin and Trotsky. At the beginning of October, Voroshilov was replaced as southern front commander by Sytin, a general of the old army, and Stalin was replaced as chief commissar by Shlyapnikov. As compensation, Stalin was appointed to the Revolutionary War Council and returned to Moscow. Conflict with Voroshilov reached a pitch and Trotsky threatened him with court-martial.

Trotsky spent the rest of the autumn and winter on the southern front. Stalin began to intrigue against Trotsky, even seeking to draw in Lenin, who refused. The role of Stalin in intriguing against Trotsky in Moscow and seeking to influence Lenin started here. Trotsky challenged Lenin on the issue and Lenin accepted there was such an intrigue but stated he had full confidence in Trotsky. Eventually, Trotsky insisted that Voroshilov be withdrawn and deployed in Ukraine. Lenin agreed. The left communists under Bukharin also intrigued against Trotsky, whom they saw as authoritarian and contrary to their libertarian ideals.

The machinations of Stalin and the Tsaritsyn group (Vorolishilov and other Red leaders from the old leadership in the south) reached a new pitch in December 1918. In a remarkable early anticipation of the slanders that were to come, they accused Trotsky of being the friend of Tsarist generals and of persecuting Bolsheviks in the army. These contrived stories found their way into Pravda, edited (as we have noted) by Bukharin. Moving to another level, two members of the Central Committee, Lashevich and Smilga accused Trotsky of sending commissars and communists to the firing squad. Trotsky replied to these stories in a confidential letter to the Central Committee at the end of December 1918, saying that only one commissar had been executed and that was for desertion, and went on the defend himself vigorously. Trotsky further took up this matter in a piece he published in 1919, called “Letter to a Friend”.

End of First World War and the German Revolution

The end of the First World War in November 1918 marked a decisive change in the situation. As part of the armistice agreement, Germany had to withdraw from all occupied territories and this it immediately began to do. But, while 11 November marked the symbolic end to the war, the defeat of the Central powers been apparent to many by the late summer. Austria, on the verge of collapse, was seeking peace as early as September. In early October, a new government came to power in Germany led by Prince Max of Baden as Chancellor and Scheidemann, the Social-Democrat, as Vice-Chancellor. The central powers made a joint proposal for an armistice to President Wilson, but discussions dragged on. Meanwhile, risings took place in Vienna and Budapest. Soviets began to be established in Germany and Austria. The Kaiser, refusing to abdicate, urged a last effort by the navy. This was thwarted by a mutiny and general strike in Kiel. The Kaiser was forced to abdicate and fled to Holland on 9 November. Under major pressure from a growing revolutionary wave, especially in Berlin and other major cities, a new Social Democratic Government was formed, calling itself (as a bluff) the Council of People’s Commissars.

While all this was going on, the excitement among the Bolsheviks in Russia was mounting. At long last, the expected workers’ revolution appeared to be taking place in Germany and Austria, and would surely be followed in France and Britain. Lenin, at this time, had just about recovered from the wounds inflicted by the attempted assassination of 30 August. The Soviet Executive pledged full support to the proletariat of Germany and Austria, instructed the Revolutionary Military Council to expand the formation of the Red Army and to set up food funds for the German and Austrian workers. Lenin addressed a meeting of the Soviet Executive at the end of October, stating that we had “never been so near a world revolution and never have we been in such a perilous position, because this is the first time that Bolshevism has been regarded as a world-wide danger.” The imperialists were undoubtedly emboldened by their victory over Germany and her allies and wanted to strike at Russian Bolshevism. But, they were hampered by two big factors. First, the war weariness of their troops and secondly, the growing sympathy of their working classes to Bolshevism and revolution.

At long last, the expected workers’ revolution appeared to be taking place in Germany and Austria. It seemed the Soviets' isolation would finally be broken / Image: public domain

At long last, the expected workers’ revolution appeared to be taking place in Germany and Austria. It seemed the Soviets' isolation would finally be broken / Image: public domain

Although Austria and Germany were ripe for revolution, one major obstacle stood in the way and that was the treacherous role played by the German and Austrian Social Democratic Party leaderships. Allegiance to revolutionary parties was growing rapidly but had not achieved what we might call critical mass. The repression of revolutionaries in Germany had taken its toll and the social democrats continued to carry the mantle of Marxism when it suited them. The release from custody of Liebknecht and Luxemburg in Germany, and Adler in Austria, in October 1918 was important but gave insufficient time to develop a significant mass revolutionary force to meet the wave of discontent at the end of the war.

The Bolsheviks tried their best to influence events in Berlin in November and December 1918, but the opposition of the German government, dominated as it was by social democrats, by and large frustrated their efforts. Joffe, the Soviet Ambassador to Berlin, was expelled on 5 November and diplomatic relations with Russia severed. Although Russia had sent clandestine support to the Spartacists (the German version of the Bolshevik Party) the strength was with the moderate socialists, backed by reaction as their best bet to stave-off revolution. But, more was needed to prevent revolution, and that was to drown the growing wave of revolt in blood. Noske, the SDP minister in charge of internal security, was to take up that task, as he demonstrated in January 1919. The murder of Liebknecht and Luxemburg, also in January 1919, effectively removed the best and most inspirational Spartacist leaders.

Escalation of imperial intervention

Once it was clear that Germany was going to be defeated in the war, France, Britain, the USA and the other allied powers stepped up both their support for the Whites and their direct intervention with troops. As Lenin had predicted, they now saw Bolshevik Russia as a dangerous example that had to be squashed, lest it infect their own countries. The British, French and Japanese had all landed forces in Russia earlier in 1918. The British and French in the northern sector had bases established in the First World War at Murmansk and Archangel, and the Japanese at Vladivostok. The Czechs were already a significant force within Russia, as has been discussed.

Allied interventions became much more serious in the summer of 1918 and Special Expeditionary Forces were established by France, Britain and the USA to strengthen their involvement. Other nations also sent small units. By the end of 1918, Russia was encircled by fronts that had both direct and indirect allied support.

The western Siberian front, where the Bolsheviks mostly clashed with the Czech legion, has already been discussed. The eastern Siberian zone was largely confined to an area around Vladivostok. British, Japanese and US warships had been sent there early in 1918 and the British and Japanese landed small forces. This was stepped up considerably in the summer of 1918, with 70,000 troops from Japan and then an international coalition of 25,000 troops from the USA, Britain, France, Canada, China, Romania, Serbia and Italy.

Allied interventions became much more serious in the summer of 1918 (Australian soliders pictured) / Image: public domain

Allied interventions became much more serious in the summer of 1918 (Australian soliders pictured) / Image: public domain

On the northern front, Britain and France had established armed depots storing military equipment and ammunition at the ports of Murmansk and Archangel in 1917 as part of the First World War efforts to strengthen Russian resolve. From the summer of 1918, the French and British and later the USA formed the Northern Expeditionary Forces of army, navy and airforce units designed to protect their supplies and to assist the Whites, especially the Czech Legion. The Canadians, Australians, Serbians and Poles also sent supportive units. In August and September 1918, these allied forces began an offensive into Bolshevik-held territory. The Bolshevik forces, however, had managed to force them back to an area just 50 miles south of the two ports.

A Baltic campaign was conducted by the British and other navies towards the end of 1918, to assist White forces in Estonia and Latvia. In December 1918, the French began a direct intervention in southern Russia, occupying Odessa on the Black Sea. The French were supported by Polish and Greek troops.

In the southwest, Romania had annexed Bessarabia (equivalent today to Moldavia and parts of the Ukraine) in March 1918.

The South Caucasus region of Russia, comprising the countries of Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan, was of particular interest to several countries, notably Turkey, who claimed Armenia; and Britain and Germany, who were keenly interested in the oil fields of Azerbaijan, centred on Baku. At the end of 1918, the British recognised the independence of Azerbaijan and Georgia, both hostile to the Bolsheviks, and sent troops to Baku to protect oil supplies and to prevent oil reaching the Reds.

There were also operations conducted in central Asia by the British. In February 1918, the Red Army overthrew the White Russian-supported Kokand autonomy of Turkestan. Allied forces began to intervene and British forces, led by Major Dunsterville, drove the Bolshevik forces out of central Asia. But this success was short-lived, and soon Dunsterville was himself forced back. The Bolsheviks continued to make progress in bringing the central Asian population under their influence. The first regional congress of the Russian Communist Party was convened in the city of Tashkent in June 1918, in order to build support for a local Bolshevik Party.

The end of 1918

When the Sixth Congress of the Soviets met between the 6-9 November 1918, to mark the first anniversary of the revolution, the mood was upbeat. The First World War had not yet stopped but it was clear that it soon end, and the hopes for world revolution looked promising. This is the opening of Lenin’s address to the delegates:

“(Comrade Lenin’s appearance in the hall is greeted with prolonged ovation) Comrades, we are celebrating the anniversary of our revolution at a time when events of the utmost importance are taking place in the international working-class movement. It has become obvious even to the most sceptical and doubting elements of the working class and working people in general that the world war will end neither by agreements nor by coercion on the part of the old government and the old ruling bourgeois class, that this war is leading the whole world as well as Russia to a world proletarian revolution and to the workers’ triumph over capital.

“Capital drenched the earth in blood, and, after the violence and outrages of German imperialism, Anglo-French imperialism, supported by Austria and Germany, is pursuing the same policy.

“Today, when celebrating the anniversary of the revolution, it is fitting that we cast a glance back along the path traversed by the revolution. We began our revolution in unusually difficult conditions, such as no other workers’ revolution in the world will ever have to face. It is therefore particularly important that we endeavour to review the path we have covered as a whole, to take stock of our achievements during this period, and see to what extent we have prepared ourselves during the past year for our chief, our real, our decisive and fundamental task.

“We must be one of the detachments, one of the units of the world proletarian and socialist army. We have always realised that it was not on account of any merit of the Russian proletariat, or because it was in advance of the others, that we happened to begin the revolution, which grew out of world-wide struggle.

“On the contrary, it was only because of the peculiar weakness and backwardness of capitalism, and the peculiar pressure of military strategic circumstances, that we happened in the course of events to move ahead of the other detachments, while not waiting until they had caught us up and rebelled. We are now making this review so as to take stock of our preparations for the battles that will face us in the coming revolution.

“And so, comrades, when we ask ourselves what big changes we have made over the past year, we can say the following: from workers’ control, the working class’s first steps, and from disposing of all the country’s resources, we are now on the threshold of creating a workers’ administration of industry; from the general peasants’ struggle for land, the peasants’ struggle against the landowners, a struggle that had a national, bourgeois-democratic character, we have now reached a stage where the proletarian and semi-proletarian elements in the countryside have set themselves apart: those who labour and are exploited have set themselves apart from the others and have begun to build a new life; the most oppressed country folk are fighting the bourgeoisie, including their own rural kulak bourgeoisie, to the bitter end.

“Furthermore, from the first steps of Soviet organisation we have now reached a stage where, as Comrade Sverdlov justly remarked in opening this Congress, there is no place in Russia, however remote, where Soviet authority has not asserted itself and become an integral part of the Soviet Constitution, which is based on long experience gained in the struggle of the working and oppressed people.

“We now have a powerful Red Army instead of being utterly defenceless after the last four years’ war, which evoked hatred and aversion among the mass of the exploited and left them terribly weak and exhausted, and which condemned the revolution to a most difficult and drastic period when we were defenceless against the blows of German and Austrian imperialism. Finally, and most important of all, we have come from being isolated internationally, from which we suffered both in October and at the beginning of the year, to a position where our only, but firm allies, the working and oppressed people of the world, have at last rebelled. We have reached a stage where the leaders of the West European proletariat, like Liebknecht and Adler, leaders who spent many months in prison for their bold and heroic attempts to gather opposition to the imperialist war, have been set free under the pressure of the rapidly developing workers’ revolutions in Vienna and Berlin. Instead of being isolated, we are now in a position where we are marching side by side, shoulder to shoulder with our international allies. Those are the chief achievements of the past year.”

The first anniversary celebrations in Petrograd were a joyous, informal affair featuring demonstrations, columns of marchers on the streets and squares of the city, and a military parade on Uritsky Square (formerly Palace Square). Marchers gathered under the famous Alexander Column, which avant-garde artist Natan Al'tman had converted into a mobile fabric torch.

In November, the Soviet government annulled the Brest-Litovsk Treaty. This was followed by turmoil and massive struggles in Ukraine. Lenin had originally not placed great store in resuming struggle in Ukraine, stressing the need to maintain efforts in the other fronts. Kolchak, having taken over the leadership of the eastern front, had rolled back the Bolshevik advances, re-taking Perma and Ufa, but was then held at this point. Lenin swung his support to Trotsky in the decision to make a concerted effort to retake Ukraine.

An international, revolutionary gathering took place in Petrograd in December 1918, presided over by Zinoviev. This was the prelude to the formation of a new Communist International, to be known as the Third International, whose first congress was held three months later in March 1919 / Image: Flickr, The Kathryn and Shelby Cullom Davis Library

An international, revolutionary gathering took place in Petrograd in December 1918, presided over by Zinoviev. This was the prelude to the formation of a new Communist International, to be known as the Third International, whose first congress was held three months later in March 1919 / Image: Flickr, The Kathryn and Shelby Cullom Davis Library

The German occupation disintegrated rapidly after the armistice. The old nationalists had also begun to re-group from September and had a volunteer army that fought against the Hetman, a German quisling. By the end of the year, Red partisans, with the support of anarchist bands under the general leadership of Makhno, had made considerable progress. The struggle for control of Ukraine was now a civil war between the old nationalist elements, representing the rich and middle peasantry; and the Red Army and its allies, representing the working class and poor peasants. The French, seeking to throw their support behind the nationalist Directorate, landed at Odessa in December 1918. They were supported by Greek, Romanian and Polish troops. They immediately started a march north to link up with the nationalist forces. This ill-fated campaign foundered early in 1919.

An international, revolutionary gathering took place in Petrograd in December 1918, presided over by Zinoviev. This was the prelude to the formation of a new Communist International, to be known as the Third International, whose first congress was held three months later in March 1919.