During the years of the reaction my work consisted chiefly of interpreting the revolution of 1905, and of paving the way for the next revolution by theoretical research. Shortly after my arrival abroad I toured the Russian émigré and student colonies with two lectures: The Fate of the Russian Revolution: Apropos the Present Political Situation, and Capitalism and Socialism: Social Revolutionary Prospects. The first lecture aimed to show that the prospect of the Russian Revolution as a permanent revolution was confirmed by the experience of 1905. The second lecture connected the Russian with the world revolution.

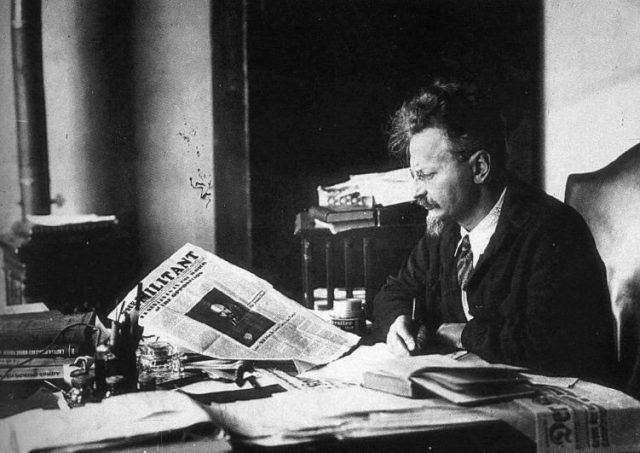

In October, 1908, I began to publish in Vienna a Russian paper, Pravda (The Truth) a paper with an appeal to the masses of workers. It was smuggled into Russia either across the Galician frontier or by way of the Black Sea. The paper was published for three and a half years as a bi-monthly, but even at that it involved a great deal of work. The secret correspondence with Russia took a lot of time. In addition, I was in contact with the underground union of Black Sea seamen and helped them to publish their organ.

My chief contributor to the Pravda was A.A. Joffe, who later became a well-known Soviet diplomatist. The Vienna days were the beginning of our friendship. Joffe was a man of great intellectual ardour, very genial in all personal relations, and unswervingly loyal to the cause. He gave to the Pravda both money and all his strength. Joffe suffered from a nervous complaint and was then being psychoanalysed by the well-known Viennese specialist, Alfred Adler, who began as a pupil of Freud but later opposed his master and founded his own school of individual psychology. Through Joffe, I became acquainted with the problems of psycho-analysis, which fascinated me, although much in this field is still vague and unstable and opens the way for fanciful and arbitrary ideas. My other contributor was a student named Skobelev, who later became the minister of labour in Kerensky’s government; we met in 1917 as enemies. I had Victor Kopp for a while as secretary of the Pravda; he is now Soviet ambassador to Sweden.

In connection with the activities of the Pravda, Joffe went to Russia for revolutionary work. He was arrested in Odessa, spent a long time in prison, and was later exiled to Siberia. He was not set free until February, 1917, as a result of the revolution of that month. In the October revolution which followed, he played one of the most active parts. The personal bravery of this very sick man was really magnificent. I can still see him in the autumn of 1919 as clearly as if it were to-day with his rather thick-set figure on the shell-ridden field below St. Petersburg. In the immaculate dress of a diplomat, with a gentle smile on his calm face and a cane in his hand, as if he were merely walking along Unter den Linden, Joffe watched the shells exploding nearby, curiously, without speeding or slowing his steps. He was a good speaker, thoughtful and earnest in appeal, and he showed the same qualities as a writer. In everything he did, he paid the most exacting attention to de tail a quality that not many revolutionaries have. Lenin had a very high opinion of his diplomatic work. For a great many years I was bound to him more closely than any one else. His loyalty to friendship as well as to principle was unequalled. Joffe ended his life tragically. Grave hereditary diseases were undermining his health. Just as seriously, too, he was being undermined by the unbridled baiting of Marxists led by the epigones. Deprived of the chance of fighting his illness, and so deprived of the political struggle, Joffe committed suicide in the autumn of 1927. The letter he wrote me before his death was stolen from his dressing-table by Stalin’s agents. Lines intended for the eyes of a friend were torn from their context, distorted and belied by Yaroslavsky and others intrinsically demoralised. But this will not prevent Joffe from being inscribed as one of the noblest names in the book of the revolution.

In the darkest days of the reaction, Joffe and I were confidently waiting for a new revolution, and we pictured it in the very way in which it actually evolved in 1917. Sverchkov, at that time a Menshevik and to-day a follower of Stalin, writes of the Vienna Pravda in his memoirs: “In this paper, he [Trotsky] continued to advocate, insistently and unswervingly, the idea of the ‘permanency’ of the Russian revolution, which argues that after the revolution has begun it cannot come to an end until it effects the overthrow of capitalism and establishes the socialist system throughout the world. He was laughed at, accused of romanticism and the seven mortal sins by both the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks. But he stuck to his point with tenacity and firmness, impervious to the at tacks.”

In 1909, writing in the Polish magazine of Rosa Luxemburg, I characterised the revolutionary relationship between the proletariat and the peasantry in the following words: “Local cretinism is the historical curse of the peasant movements. It was on the circumscribed political intelligence of the peasant who while in his village plundered his landlord in order to seize his land, but then, decked out in a soldier’s coat, shot down the workers, that the first wave of the Russian revolution (1905) broke. The events of that revolution may be regarded as a series of ruthless object-lessons by means of which history is hammering into the head of the peasant the consciousness of the ties which connect his local demand for land with the central problem of the state power.”

Quoting the example of Finland, where the Social Democracy won great influence among the peasants by its stand on the question of the small-farmer, I concluded: “What great influence will our party then wield over the peasantry, in the exercise of its leadership of a new and much more widespread movement of the masses in town and country! Provided, of course, that we do not lay down our arms in our fear of the temptations of political power to which we will inevitably be subjected by the new wave to come.”

How much like “ignoring the peasantry” or “jumping over the agrarian question,” that is!

On December 4, 1909, at a time when the revolution seemed to have been hopelessly and permanently trampled under, I wrote in the Pravda: “Even to-day, through the black clouds of the reaction which have surrounded us, we envisage the victorious reflection of the new October.” Not only the liberals but the Mensheviks as well ridiculed these words, which they regarded as a mere slogan for agitation, as a phrase without content. Professor Miliukoff, to whom the honour of coining the term “Trotskyism” belongs, retorted: “The idea of dictatorship by the proletariat is purely childish, and there is not a man in Europe who will support it.” And yet there were events in 1917 which must have shaken the magnificent confidence of the liberal professor.

During the years of the reaction I studied the questions of trade and industry both on a world scale and a national scale. I was prompted by a revolutionary interest. I wanted to find out the relationship between the fluctuations of trade and industry, on the one hand, and the progressive stages of the labour movement and revolutionary struggle, on the other. In this, as in all other questions like it, I was especially on my guard to avoid establishing an automatic dependence of politics on economics. The interaction must necessarily be the result of the whole process considered in its entirety.

I was still living in the little Bohemian town of Hirschberg when the New York stock exchange suffered the “Black Friday” catastrophe. This was the harbinger of a world crisis which was bound to engulf Russia as well, shaken to her foundations as she was by the Russo-Japanese war, and by the ensuing revolution. What consequences could be expected? The point of view generally accepted in the party, without distinction of faction, was that the crisis would serve to heighten the revolutionary struggle. I took a different stand. After a period of big battles and defeats, a crisis has the effect of depressing rather than arousing the working class. It under mines the workers’ confidence in their powers and demoralises them politically. Under such conditions, only an industrial revival can close the ranks of the proletariat, pour fresh blood into its veins, restore its confidence in itself and make it capable of further struggle.

This analysis was met by criticism and incredulity. The official party economists also put forward the idea that under the counter-revolution a trade boom was impossible. In opposition, I based my argument on the inevitability of an economic revival and of the new wave of strikes it would bring in its wake, after which a new economic crisis would be likely to provide the impetus for a revolutionary struggle. This prognosis was confirmed to the letter. An industrial boom came in 1910, in spite of the counter-revolution and with it came strikes. The shooting down of the workers at the Lena gold mines in 1912 gave rise to great protests all over the country. In 1914 when the crisis was unmistakable, St. Petersburg again became an arena of workers’ barricades. They were witnessed by Poincaré, who visited the Czar on the eve of the war.

This theoretical and political test was invaluable in my future activities. At the Third Congress of the Communist International, I had an overwhelming majority of the delegates against me when I insisted on the inevitability of an economic revival in post-war Europe as a condition for further revolutionary crises. And again in recent times, I had to bring against the Sixth Congress of the Communist International the charge of utter failure to understand the break in the economic and political situation in China, a failure which found expression in unwarranted hopes that the Chinese revolution, in spite of the disastrous defeats it had suffered, would continue to progress because of the country’s growing economic crisis.

The dialectics of the process are really not very complex. But they are easier to formulate than to discover every time in the living facts. At any rate, in the discussions of this question I am constantly coming across the most tenacious prejudices, which lead in politics to grave errors and painful consequences.

In its view of the future of Menshevism, and of the problems of organisation within the party, the Pravda never arrived at the preciseness of Lenin’s attitude. I was still hoping that the new revolution would force the Mensheviks as had that of 1905 to follow a revolutionary path. But I under estimated the importance of preparatory ideological selection and of political case-hardening. In questions of the inner development of the party I was guilty of a sort of social-revolutionary fatalism. This was a mistaken stand, but it was vastly superior to that bureaucratic fatalism, devoid of ideas, which distinguishes the majority of my present-day critics in the camp of the Communist International.

In 1912, when the political curve in Russia took an unmistakable upward turn, I made an attempt to call a union conference of representatives of all the Social Democratic factions. To show that I was not alone in the hope of restoring the unity of the Russian Social Democracy, I can cite Rosa Luxemburg. In the summer of 1911, she wrote: “Despite everything, the unity of the party could still be saved if both sides could be forced to call a conference together.” In August, 1911, she reiterated: “The only way to save the unity is to bring about a general conference of people sent from Russia, for the people in Russia all want peace and unity, and they represent the only force that can bring the fighting-cocks abroad to their senses.”

Among the Bolsheviks themselves, conciliatory tendencies were then still very strong, and I had hoped that this would induce Lenin also to take part in a general conference. Lenin, however, came out with all his force against union. The en tire course of the events that followed proved conclusively that Lenin was right. The conference met in Vienna in August, 1912, without the Bolsheviks, and I found myself formally in a “bloc” with the Mensheviks and a few disparate groups of Bolshevik dissenters. This “bloc” had no common political basis, because in all important matters I disagreed with the Mensheviks. My struggle against them was resumed immediately after the conference. Every day, bitter conflicts grew out of the deep-rooted opposition of the two tendencies, the social-revolutionary and the democratic-reformist.

“From Trotsky’s letter,” writes Axelrod on May 4, shortly before the conference, “I got the very painful impression that he had not the slightest desire to come to a real and friendly understanding with us and our friends in Russia ... for a joint fight against the common enemy.” Nor had I, in fact, nor could I possibly have had, an intention of allying myself with the Mensheviks to fight against the Bolsheviks. After the conference, Martov complained in a letter to Axelrod that Trotsky was reviving the “worst habits of the Lenin-Plekhanov literary individualism.” The correspondence between Axelrod and Martov, published a few years ago, testifies to this perfectly unfeigned hatred of me. Despite the great gulf which separated me from them, I never had any such feeling toward them. Even to-day, I gratefully remember that in earlier years I was indebted to them for many things.

The episode of the August bloc has been included in all the “anti-Trotsky” text-books of the epigone period. For the benefit of the novices and the ignorant, the past is there presented in such a way as to suggest that Bolshevism came out of the laboratory of history fully armed whereas the history of the struggle of the Bolsheviks against the Mensheviks is also a history of ceaseless efforts toward unity. After his return to Russia in 1917, Lenin made the last effort to come to terms with the Mensheviks-Internationalists. When I arrived from America in May of the same year, the majority of the Social Democratic organisations in the provinces consisted of united Bolsheviks and Mensheviks. At the party conference in March, 1917, a few days before Lenin’s arrival, Stalin was preaching union with the party of Tzereteli. Even after the October revolution, Zinoviev, Kamenev, Rykov, Lunacharsky and dozens of others were fighting madly for a coalition with the Social Revolutionaries and the Mensheviks. And these are the men who are now trying to sustain their ideological existence by hair-raising stories about the Vienna unity conference of 1912!

The Kievskaya Mysl (The Kiev Thought) made me an offer to go to the Balkans as its military correspondent. The proposal was all the more timely because the August conference had already proved to be abortive. I felt that I must break away, if only for a short time, from the interests of the Russian émigrés. The few months that I spent in the Balkans were the months of the war, and they taught me much.

In September, 1912, I was on my way to the East, believing that war was not only probable but inevitable. But when I found myself on the pavements of Belgrade, and saw long lines of reservists; when I saw with my own eyes that there was no way back, that war was coming, almost any day; when I learned that a number of men whom I knew well were already in arms on the frontier, and that they would be the first to kill or be killed, then war, which I had treated so lightly in my thoughts and my articles, seemed utterly incredible and impossible. I watched, as if it were a phantom, a regiment going to war the eighteenth infantry regiment, in uniforms of protective colouring and bark sandals, and wearing a sprig of green in their caps. The sandals on their feet and the little sprig of green in their caps, in combination with the full fighting outfit, gave the soldiers the look of men doomed for sacrifice. At that moment, nothing so deeply burned the madness of war into my consciousness as those sprigs and bark sandals. How far the present generation has come from the habits and moods of 1912! I understood even then that the humanitarian, the moral, point of view of the historical process was the most sterile one. But it was the emotion, not its explanation, that mattered then. A sense of the tragedy of history, which words cannot suggest, was taking possession of me; a feeling of impotence before fate, a burning compassion for the human locust.

War was declared two or three days later. “You in Russia know it, and believe in it,” I wrote, “but here, on the spot, I do not believe in it. My mind does not accept this combination of the things of everyday life, of chicken, cigarettes, bare footed and smut-nosed boys, with the incredibly tragic fact of war. I know that war has been declared, and that it has already begun, but I have not yet learned to believe in it.” I had to learn this, however, decisively and for a long time.

The years 1912-13 gave me a close acquaintance with Serbia, Bulgaria, Roumania and with war. In many respects, this was an important preparation not only for 1914, but for 1917 as well. In my articles, I launched attacks on the falsity of Slavophilism, on chauvinism in general, on the illusions of war, on the scientifically organised system for duping public opinion. The editors of the Kievskaya Mysl had the courage to print my article describing the Bulgarian atrocities on the wounded and captured Turks, and exposing the conspiracy of silence on the part of the Russian press. This brought forth a storm of indignant protests from the liberal papers. On January 30, 1913, I published in the newspaper an “ex-parliamentary question” to Miliukoff concerning the Slav atrocities to the Turks. Miliukoff, the permanent defence-attorney of official Bulgaria, was cornered and answered stammeringly. The controversy lasted for several weeks, with the government papers as was inevitable dropping hints that the pen name “Antid Oto” disguised not only an émigré but also an agent of Austria-Hungary.

The month I spent in Roumania brought me into close co tact with Dobrudjanu-Gherea, and cemented my friendship with Rakovsky, whom I had known since 1903, forever.

A Russian revolutionary of the seventies stopped in Roumania in passing, on the very eve of the Russo-Turkish war; he was detained for a while by circumstances beyond his control; a few years later, under the name of Gherea, he had won far-reaching influence over the Roumanian intelligentsia, extending it later to the more advanced among the workers as well. Literary criticism on a social basis was Gherea’s chief medium for shaping the more advanced groups among the Roumanian intelligentsia. Then, from questions of aesthetics and personal ethics, he led them to scientific socialism. The majority of Roumanian politicians of almost every party passed through, at least in their younger days, a brief school of Marxism under Gherea’s guidance. It did not prevent them, however, from pursuing a policy of reactionary banditry in their riper age.

Ch.G. Rakovsky is, internationally, one of the best-known figures in the European socialist movement. A Bulgarian by birth, Rakovsky comes from the town of Kotel, in the very heart of Bulgaria, but he is a Roumanian subject by dint of the Balkan map, a French physician by education, a Russian by connections, by sympathies and literary work. He speaks all the Balkan and four European languages; he has at various times played an active part in the inner workings of four Socialist parties the Bulgarian, Russian, French, and Roumanian to become eventually one of the leaders of the Soviet Federation, a founder of the Communist International, president of the Ukrainian Soviet of People’s Commissaries, and the diplomatic Soviet representative in England and France only to share finally the fate of all the “left” opposition. Rakovsky’s personal traits, his broad international outlook, his profound nobility of character, have made him particularly odious to Stalin, who personifies the exact opposite of these qualities.

In 1913, Rakovsky was the organiser and leader of the Roumanian Socialist party, which later joined the Communist International. The party was showing considerable growth. Rakovsky edited a daily paper, which he financed as well. On the coast of the Black Sea, not far from Mangalia, he owned a small estate which he had inherited, and with the income from it he supported the Roumanian Socialist party and several revolutionary groups and individuals in other countries. Every week he spent three days in Bucharest, writing articles, directing the sessions of the Central Committee, and speaking at meetings and street demonstrations. Then he would dash over to the Black Sea coast by train, carrying with him to his estate binder-twine, nails and other appurtenances of country life; he would drive out into the fields, watching the work of a new tractor, running behind it along the furrow in his frock-coat; then, a day later, he would be speeding back to town so as not to be late for a public meeting, or for some private session. I accompanied him on one of his trips, and could not but admire his superabundant energy, his tirelessness, his constant spiritual alertness, and his kindness to and concern for unimportant people. Within fifteen minutes on a street in Mangalia, Rakovsky would switch from Roumanian to Turkish, from Turkish to Bulgarian, and then to German and French when he was talking to colonists or to commercial agents; then, finally, he would speak Russian with the Russian Skoptsi, who are numerous in the adjoining district. He would carry on conversations as a landlord, as a doctor, as a Bulgarian, as a Roumanian subject, and chiefly, as a Socialist. In these aspects, he passed before my eyes like a living miracle on the streets of this remote, leisurely and carefree little maritime town. And the same night he would again be dashing to the field of battle by train. He was always at ease and self-confident, whether he was in Bucharest or Sophia, in Paris, St Petersburg, or Kharkoff.

The years of my second foreign exile were years spent in writing for the Russian democratic press. I made my debut in the Kievskaya Mysl with a long article on the Munich journal, Simplicissimus, which at one time interested me so much that I went through all its issues from the very first one, when the cartoons by T.T. Heine were still impregnated with a poignant social feeling. My closer acquaintance with the new German fiction belongs to the same period. I even wrote a long social-critical essay on Wedekind, because interest in him was increasing in Russia with the decline of the revolutionary moods.

In the south of Russia, the Kievskaya Mysl was the most popular radical paper of the Marxist hue. A paper like it could exist only in Kiev, with its feeble industrial life, its undeveloped class contradictions, and its long-standing traditions of intellectual radicalism. Mutatis mutandis, one can say that a radical paper appeared in Kiev for the same reason that Simplicissimus appeared in Munich. I wrote there on the most diverse subjects, sometimes very risky as regards censorship. Short articles were often the result of long preparatory work. Of course I couldn’t say all that I wanted to in a legally published, non-partisan paper. But I never wrote what I did not want to say. My articles in the Kievskaya Mysl have been republished by a Soviet publishing house in several volumes; I didn’t have to recant a thing. It may not be superfluous for the present moment to mention that I contributed to the bourgeois press with the formal consent of the Central Committee, on which Lenin had a majority.

I have already mentioned that immediately after our arrival in Vienna, we took quarters out of town. “Hütteldorf pleased me,” wrote my wife. “The house was better than we could usually get, as the villas here were usually rented in the spring, and we rented ours for the autumn and winter. From the windows we could see the mountains, all dark-red autumn colours. One could get into the open country through a back gate without going to the street. In the winter, on Sundays, the Viennese came by on their way to the mountains, with sleds and skis, in little coloured caps and sweaters. In April, when we had to leave our house because of the doubling of the rent, the violets were already blooming in the garden and their fragrance filled the rooms from the open windows. Here Seryozha was born. We had to move to the more democratic Sievering.

“The children spoke Russian and German. In the kindergarten and school they spoke German, and for this reason they continued to talk German when they were playing at home. But if their father or I started talking to them, it was enough to make them change instantly to Russian. If we addressed them in German, they were embarrassed, and answered us in Russian. In later years, they also acquired the Viennese dialect and spoke it excellently.

“They liked to visit the Klyachko family, where they received great attention from everybody the head of the family, his wife, and the grown-up children and were shown many interesting things and treated to others. The children were also fond of Ryazanov, the well-known Marxian scholar, who was then living in Vienna. He caught the imagination of the boys with his gymnastic feats, and appealed to them with his boisterous manner. Once when the younger boy Seryozha was having his hair cut by a barber and I was sitting near him, he beckoned to me to come over and then whispered in my ear: ‘I want him to cut my hair like Ryazanov’s.’ He had been impressed by Ryazanov’s huge smooth bald patch; it was not like every one else’s hair; but much better.

“When Lyovik entered the school, the question of religion came up. According to the Austrian law then in force, children up to the age of fourteen had to have religious instruction in the faith of their parents. As no religion was listed in our documents, we chose the Lutheran for the children because it was a religion which seemed easier on the children’s shoulders as well as their souls. It was taught in the hours after school by a woman teacher, in the schoolhouse; Lyovik liked this lesson, as one could see by his little face, but he did not think it necessary to talk about it. One evening I heard him muttering something when he was in bed. When I questioned him, he said, ’It’s a prayer. You know prayers can be very pretty, like poems.’”

Ever since my first foreign exile, my parents had been coming abroad. They visited me in Paris; then they came to Vienna with my oldest daughter 1, who was living with them in the country. In 1910 they came to Berlin. By that time they had become fully reconciled to my fate. The final argument was probably my first book in German.

My mother was suffering from a very grave illness (actinomycosis). For the last ten years of her life, she bore it as if it were simply another burden, without stopping her work. One of her kidneys was removed in Berlin; she was sixty then. For a few months after the operation, her health was marvellous, and the case became famous in medical circles. But her illness returned soon after, and in a few months she passed away. She died at Yanovka, where she had spent her working-life and had brought up her children.

The long Vienna episode in my life would not be complete without mention of the fact that our closest friends there were the family of an old émigré, S.L. Klyachko. The whole history of my second foreign exile is closely intertwined with this family. It was a centre of political and intellectual interests, of love of music, of four European languages, of various European connections. The death, in April, 1914, of the head of the family, Semyon Lvovich, was a great loss to me and my wife. Leo Tolstoy once wrote of his very talented brother, Sergey, that he lacked only a few small defects to make him a great artist. One could say the same of Semyon Lvovich. He had all the abilities necessary to attain great prominence in politics, except that he hadn’t the necessary defects. In the Klyachko family, we always found friendship and help, and we often needed both.

My earnings at the Kievskaya Mysl were quite enough for our modest living. But there were months when my work for the Pravda left me no time to write a single paying line. The crisis set in. My wife learned the road to the pawn-shops, and I had to resell to the booksellers books bought in more affluent days. There were times when our modest possessions were confiscated to pay the house-rent. We had two babies and no nurse; our life was a double burden on my wife. But she still found time and energy to help me in revolutionary work.

Notes

1. [By the author’s first marriage.]↩