Over the past couple of years Peña Nieto's government in Mexico has taken giant steps in carrying out reforms which the big bourgeoisie for a long time could only dream of. It presented itself as an unstoppable government which the workers' movement could not confront in a serious manner. But decades of such attacks and struggles have led to a build-up of pressure below the surface that constitutes a great challenge to the system and the regime that supports it. A feeling that things are not going well and that we must act to radically transform the system is taking root in Mexican society.

[Read part two here]

[Read part two here]

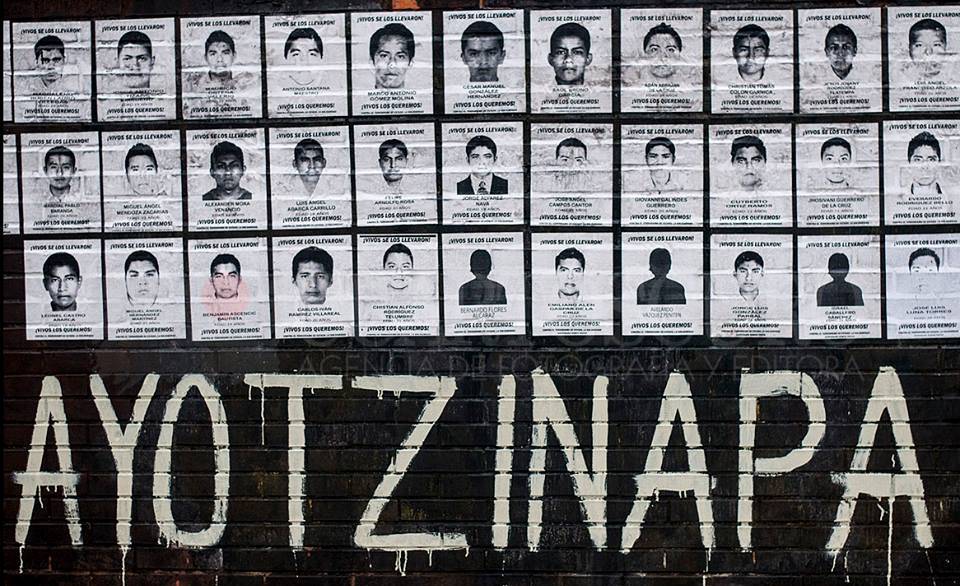

One example is the struggle of the students of the National Polytechnic Institute, who went on strike for 76 days in a battle for their future, for higher quality democratic education. It was almost at the same time that 44 IPN schools began a general strike, the events in Ayotzinapa, where three students were murdered and 43 more disappeared, shook the whole country and turned the eyes of the world to Mexico.

The newspaper Reforma remarked, on December 1st, that in the last four months Peña Nieto's approval rating fell from 50% to 39%, while 81% of the population see his fight against violence as bad or very bad and regarding the fight against corruption 72% disapprove of government measures. El Universal for its part said that 54% of people think that the current government is at its worst moment while the Excelsior newspaper said that 60% of Mexicans are against how the president is governing. (El País, 2 December 2014).

After the Iguala case, the president's reputation has fallen still further with the discovery that his wife, Angélica Rivera, had purchased a 7 million dollar home; the company that built the house was involved in a Chinese-funded railroad construction project worth around 3.75 billion dollars that they had to cancel.

A clear demonstration of the government's lack of prestige is that Televisa, the media empire that had given support and air time to Peña Nieto since before he was a presidential candidate, has distanced itself. Loret de Mola, a renowned news commentator, and Eugenio Derbéz, one of its most popular comedians, have made critical comments "supporting" the cause of the Ayotzinapa families and criticizing the government.” They sent him the message: "If you go down, you're going down alone; you're not taking us with you". Faced with this distancing, Peña Nieto said on December 7 that Televisa is a source of pride for Mexicans.

Time magazine in the US, in early 2014, had put Peña Nieto on its cover with the headline, “Saving Mexico”. Last November, the same magazine said: "[The Ayotzinapa case] has provoked a political upheaval of a size Mexico hasn't seen in generations—perhaps since the 1910 revolution". It is possible that the protests aren't larger than those in 2006 against electoral fraud, but the discredit to the regime is enormous and the masses are making it clear that they want to put an end to a daily life of chaos, poverty and violence that they experience under Mexican capitalism.

The terror continues

In the first week of December alone, at least four students were murdered. Two of them were from the UNAM, another was Erika Bravo from Michoacán who was skinned alive, and the last was Edith Gutiérrez, a student at the polytechnic who was murdered when returning home after leaving a student assembly at her school during the strike. Some of these crimes may not have been politically motivated, but they nonetheless reflect the reality of a system that murders whatever is most alive in society: the youth.

The violence takes place on a daily basis. In 2010, 72 migrants were found assassinated in San Fernando, Tamaulipas; between April and October 2011, more than 330 human remains were found in secret mass graves in Durango; in May 2012, 49 bodies were stacked on a highway in Nuevo León. On July 30, 2014, in Tlataya in the state of Mexico, the army executed 15 people who had surrendered after a shootout. The events in Ayotzinapa have brought to the fore the fact that the state of Guerrero is riddled with secret mass graves, murders, and disappearances. The problem goes well beyond the 43 students. Amnesty International has denounced the disappearances of more than 22,000 people, more than 5,000 of which occurred in 2014 alone. Massacres, beheadings, murders... This is the day-to-day reality. How have things come to this?

From reforms to counter-reforms

The root of all this social decay is to be found, in the first place, in the constant deterioration of the living standards of the masses, overexploitation, chronic unemployment, and the looting of the country by the big national and foreign capitalists. According to the OECD, currently 22% of young people between 15 and 29 years of age neither study nor work, a figure that represents 7,337,520 people.

Mexico, thanks to its revolution and to the industrial development that was generated in the subsequent decades, created a genuine welfare state. Between 1934 and 1981 the economy grew by more than 6% annually. To be able to develop capitalism, the state had to intervene in the economy: oil, electricity, and banks were nationalized, as well as the majority of the telecommunications industry (Telmex), and thousands of enterprises were state-owned, including steelworks, mines, fertilizer factories, etc.

The Mexican Revolution, although it did not bring real social justice to workers and peasants—which would only have been possible with the takeover of power by the workers, in alliance with the peasants, and the establishment of a democratic planned economy—it did give them important concessions, creating large welfare institutions of social security such as the IMSS and the ISSSTE. In 1965 there were 870 hospital units and clinics and 7900 doctors; by 1980 there were already 8100 clinics and hospitals and more than 52,000 doctors. Workers’ housing complexes were built, such as FOVISSTE or the INFONAVIT, as well as the CONASUPO, which still prices milk affordably to ensure that children have access to it, etc.

In the 1930s, under Lázaro Cárdenas, the National Polytechnic Institute was created to train the technicians that were needed to develop the country. This period also saw the formation of the Rural "Normal" Schools, institutions of popular education in the rural areas, which included the ideas of socialism in their syllabi. But as Trotsky (who lived in the country at the time and drew up a balance sheet of this experience) explained, it is not possible to have a socialist education without socialism. In the 1950s, in Chapingo, State of Mexico, an estate was expropriated from wealthy landowners and became a school for poor peasants, which still today holds as its motto: "exploit the land, not the people". Education flourished at every level. The UNAM in 1924 had 9,000 students, 72,000 in 1964, and almost 300,000 in 1980.

The constitution of 1917 has a bourgeois character. Nonetheless, the armed peasants and workers meant that it had also to express rights for the workers in the countryside and the cities. There have been great upswings in the workers' struggles that allowed progress in obtaining concessions and rights, as was seen in the 1920s, in the 1930s with Cárdenas, and in the so-called Union Insurgency of the 1970s.

We do not wish to give an idealised vision of the regime that emerged from the revolution. The Bonapartist state balanced between the classes while always defending the capitalist system, giving concessions to sections of the masses while harshly repressing its opponents, with a prime example being the repression of the teachers' strike of 1954 and the railroad workers' strike of 1958, the assassination of the peasant leader Rubén Jaramillo in 1962, the repression of the doctors' movement in 1964–65, the massacre of students on October 2, 1968, the dirty war of the 1970s where hundreds of activists were disappeared, the assassination of over 500 PRD militants when the party still had mass support, the repression carried out against the Zapatista struggle and the indigenous communities in gruesome incidents such as in the Acteal massacre of 1997, other massacres such as Aguas Blancas or el Charcho in Guerrero, the violent cracking down of the UNAM university strike in 2000, the repression of the people of Atenco in 2006, when Peña Nieto governed the state of Mexico, the violent eviction of the Zócalo in 2013 when the teachers held a sit-in, the political prisoners of the Peña Nieto period and earlier or the arbitrary repression of demonstrators who demanded the return of the 43 Ayotzinapa students—these are just a few examples of the regime's real character.

Despite the reactionary character of the regime that sustains Mexican capitalism, in the past there was some progress in the form of industrial development and, in fact, concessions were made to the masses under the pressure of the workers' struggles. But today we don't see reforms, but counter-reforms. What is happening in Mexico is a local expression of the crisis of capitalism, which in one country after another crushes all the gains that had been won in the past. In civilized Europe, working-class Greeks, Spaniards, Italians, or Portuguese understand this well.

A parasitic bourgeoisie

It was under the government of Miguel de la Madrid (1982–88) that the anti-worker offensive began, and was intensified under the Salinas government (1988–94). State-owned enterprises have been privatized as the state has nurtured the new, parasitic national bourgeoisie, the economy has been tied ever more closely to the United States; the countryside has been destroyed by importing more corn (Mexico’s staple) than is internally produced, forcing the farmers to look for alternative means of survival in migration or by growing drug crops; collective bargaining agreements have been destroyed, unions have been busted, the working day has been intensified and extended, and wages cut. Official figures estimate that 42% of Mexicans are poor.

It was under the government of Miguel de la Madrid (1982–88) that the anti-worker offensive began, and was intensified under the Salinas government (1988–94). State-owned enterprises have been privatized as the state has nurtured the new, parasitic national bourgeoisie, the economy has been tied ever more closely to the United States; the countryside has been destroyed by importing more corn (Mexico’s staple) than is internally produced, forcing the farmers to look for alternative means of survival in migration or by growing drug crops; collective bargaining agreements have been destroyed, unions have been busted, the working day has been intensified and extended, and wages cut. Official figures estimate that 42% of Mexicans are poor.

In 1987, when Forbes began publishing its list of the richest men in the world, Garza Sada was the only Mexican capitalist who appeared—four years later he was joined by Emilio Azcárraga. In 2013 already there were 35 Mexicans on the list, with one of them at the top: Carlos Slim. In reality it should be 36 Mexicans, since Chapo Guzmán was taken off the list for political reasons and not because he had ceased to be a prominent entrepreneur in the drugs industry. The fortunes of the 35 richest Mexican men on the Forbes list totalled nearly $170 billion (data from Martí Batres G., El gran Fracaso: las cifras del desastre neoliberal mexicano, Brigada para leer en libertad).

The Mexican bourgeoisie has historically been parasitic, subordinate to imperialism, and incapable of playing a progressive role. The state had to intervene in order to have any kind of development. One statistic that demonstrates this is that in the 1980s, $30 billion of state revenues came from the sale of state industries, but it would later cost $90 billion to bail out those very same privatized businesses.

The state plays the role of overprotective mother of the capitalists. Pemex had earmarked 70% of its income for the public treasury ($63 billion in 2011), representing 40% of the state budget. For its share, America Movil only allots 6.1% of its income for taxes, Telmex 6.5%, Peñoles 9.2%, Walmart 2.1%, Televisa 5%, Bimbo 2.3%... The sum of all the taxes paid by private companies would not equal the yield of Pemex (Ibid.).

In 1982 there were 1,155 publicly owned companies; by 1993 only 213 remained. But key industries like energy still remained under state control, and a whole series of laws made it difficult for the capitalists to go further in busting the unions and overexploiting the working class. In 2 years, the Peña Nieto government advanced the legalization and application of the programme of the bourgeoisie on a massive scale.

The year that Peña Nieto took office, in 2012, researchers at the UNAM, the Centre for Multidisciplinary Analysis, carried out a study on the productivity of Mexican workers in which it observed that in just 9 minutes of work, a worker generated a minimum daily wage, and that therefore workers earning the minimum wage gave 7 hours and 51 minutes of free labour to the employers and the state. With the reform to the Federal Labour Law, an even greater reduction in the price of labour power became possible. The wealth that the capitalists creamed off each day was enormous. Capitalism, on its own, does not develop industry and create jobs; unemployment is chronic, and can only be resolved by a whole range of individual solutions. Today 41% of jobs are in the formal economy, as against 59% in the informal sector, which goes from small business owners to domestic servants, to those who clean car windshields at intersections.

Peña Nieto's reforms

The labour reform was the first of the major reforms passed during the Peña Nieto presidency, encouraging casual labour through seasonal or hourly contracts, making dismissals cheaper and easier, making it almost impossible to get a pension, and making it easier to attack unions.

The second step was to hit the permanent workers, especially in the key unions which have kept struggling. Given that the electricians of Central Light and Power, organized in the powerful Mexican Electricians' Union (SME), were all fired in 2008, under Felipe Calderón's PAN government, the next sector attacked was the teachers, with the biggest union in Latin America, the SNTE, generally controlled by bureaucrats (charros) that are loyal to the bosses, but that have to deal with a very combative left wing, the National Coordinator of Education Workers (CNTE).

The "education reform" approved during Peña Nieto's administration is, in reality, a labour reform for the workers in basic education. Moreover, it wants the state to financially disengage part of its resources—for the maintenance and functioning of the schools—requiring these funds to be raised by parents and students.

The fiscal reform was less aggressive than originally desired, a 16% VAT on medicine, food, and books. Finally, a fiscal policy was imposed that hit small and medium sized businesses harder and imposed new taxes in the border areas, protecting at all times the big businesses for whom a loose fiscal regime continues that allows them to virtually pay no taxes.

Another reform targeted the telecommunications sector, which exposed a conflict between different sectors of the bourgeoisie, with Carlos Slim (Miss America) on the one side and Emilio Azcarraga (Televisa) on the other. This reform favours television. It also promotes censorship and espionage by the Mexican state. Added to the latter, they have taken other measures against the struggles of the workers and the youth which limit mobility and justifies repression (Such as in the Bala en Puebla law). In the midst of the Ayotzinapa protests, the Chamber of Deputies approved constitutional changes which open the way in the near future for the approval of laws limiting and prohibiting demonstrations.

The approval of the energy reform marks a real turning point. Lázaro Cárdenas's government nationalized the oil industry as a measure against the pillaging by British and US imperialists, with the objective of attaining national development along capitalist lines. This is the principal industry of the country, and has provided decades of stability. Today there is a great dependence on oil exports.

The approval of the energy reform marks a real turning point. Lázaro Cárdenas's government nationalized the oil industry as a measure against the pillaging by British and US imperialists, with the objective of attaining national development along capitalist lines. This is the principal industry of the country, and has provided decades of stability. Today there is a great dependence on oil exports.

With this reform, the state-owned electricity and oil companies will be open to private capital getting involved. More specifically, a big part of the earnings which previously went to the state treasury will now line the pockets of private capitalists, shrinking the state budget, and leading to cuts in social spending (healthcare, education, etc.). There will be layoffs and a worsening of conditions for oil and electrical workers. There will also be energy price hikes which will affect working families.

These reforms—and above all, the labour and energy reforms—represent a real turning point. We face the overthrow of the great conquests of the Mexican Revolution, placing the country at the mercy of the capitalist robbers, enabling them to plunder and exploit it. In the midst of the global capitalist crisis, the Mexican state puts the country up for sale and facilitates the exploitation of its workers in order to attract private investment. Even if this works, it will not result in any improvement for the masses who will pay, with our sweat and blood, the cost of these reforms.

The "war on drugs" and imperialist meddling

These attacks are part of the explanation of the situation in Mexico today. As for the violence, this exploded when Felipe Calderón came to power. That year saw one of the largest mobilisations in the country with very militant strikes by miners and metal workers, demonstrations of up to three million people and the creation of the Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca, an embryonic soviet which challenged the power of the local state apparatus, headed by Ulises Ruiz.

Anthony Garz, then US ambassador to Mexico, described Calderon’s assumption of the presidency as taking place in "the greatest possible situation of political weakness" adding in an internal cable revealed by Wikileaks that: "We are running the risk that the matters that are important to us might be blocked, unless we can send a strong signal of support for the future president to implement his agenda”.

From the beginning, imperialism did whatever it could to save a government that had been shaken by the revolutionary struggle of the masses. A representative of the Bush administration stated that "a team from the mission under my command will be actively involved with the transition team of Calderón to promote and advance the areas that are priorities to us." He concluded that Felipe Calderon "will need much support from the US government" (La Jornada, 21/2/2011).

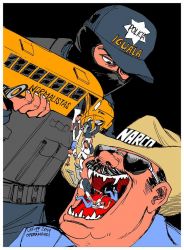

It was in this context that the war against drug trafficking was launched, which meant the militarisation of the country and a way of getting people back to go home and bringing an end to the revolutionary movement of the masses. That broke all equilibrium between the drug cartels and was a catalyst to accelerate the contradictions. It triggered a violent struggle for the drug markets, where the Calderon government intervened to support Chapo Guzman and his Sinaloa cartel, but all the cartels brought in corrupt police, judges and governors to act on their behalf.

The imperialists permanently kept advisers from the DEA and the CIA on the ground in Mexico. Many of the weapons used in this war came from the US, and operations with such names as "Fast and Furious" saw a massive influx of arms that ended up in the hands of the cartels. On one occasion, a plane carrying drugs for Chapo Guzman crashed in Yucatan and it was revealed that this plane was previously used by the CIA.

The USA is the biggest consumer on the planet and drugs are no exception, comprising over 50% of the world’s total drug market. The drug business in Mexico cannot be understood without taking into account the enormous consumption in the USA.

In the Calderon era, the Secretary of Public Security and its head, Garcia Luna, acted more like a cartel than a government department, or rather acted in the interests of the cartels. At least between January 2007 and November 2009, the Secretary of Public Security (SPS) used a series of hangars in the Toluca International Airport. "In these hangars planes from Venezuela and Colombia unloaded tons of cocaine with the protection of the SPS". They used Cancun airport, where the plains descended under the pretext of refuelling, and in that way the status of the flight was changed from national to international under the status of the SSP. The Mexico City airport has also been used for massive drug trafficking. This is the reality of Calderon's "war on drugs', using one of his closest men, Garcia Luna to cover up and protect the drug traffickers (Anabel Hernandez, Mexico on Fire: The Legacy of Calderon, Grijalbo).

With Peña Nieto things have changed superficially, but in essence the situation continues to be the same. Social decomposition continues to advance. Organized crime does not just keep to the drug trade, but meddles in all kinds of illegal business. In cartel-controlled areas, any illegal enterprise not controlled by them is viewed as competition which must be co-opted or elbowed out.

The Obama administration has shown its concern for Mexico and has offered its help in finding the 43 Normalistas. What worries the imperialists is not the disappeared students, but the weakness of the regime. Peña Nieto met with US Secretary of Homeland Security Jeh Johnson in December, and one can be sure that they did not only talk about immigration and drug trafficking. Just like in 2006, the imperialists are trying to take measures to save the regime from the mass revolutionary struggle.

Diversification of illegal business

Without changing the conditions that give rise to organized crime, the problem of violence will persist. Even in cases where the cartels have been dealt real blows, this does not solve the problem of violence; on the contrary, this intensifies it, leaving behind uncontrolled criminal gangs. Journalist Anabel Hernández explains that, "There are mercenary groups operating in Mexico; criminals who form part of one of the country's important cartels, or its cells, but which, in the face of the dismembering of said organizations, now reform themselves as their own, gravely dangerous groups" (Ibid.).

Groups of mercenary thugs have been created in the country that do their job very effectively, and who sell their services to the highest bidder. Other detached cartel cells go it alone, extorting and using force on the population. The State of Mexico, surrounding the Federal District and for the past two years governed by Peña Nieto, has been turned into one of the most violent areas in the country.

The PAN government of Felipe Calderon and the PRI government of Pena Nieto have not sought to end drug trafficking. If they wanted to do so, they would have attacked the cartels economically, preventing money laundering and freezing their accounts. In 2012 the DEA calculated that in the US, $65 billion was destined to be spent buying illegal drugs, of which only $1 billion was confiscated, and calculated that something between $19 and $29 million dollars flowed from the US into the Mexican cartels. It is thought that the larger part of the profits from drug trafficking is laundered within the US itself, but that in Mexico $10 billion are laundered annually (The Economist, 04/07/2012). Drugs have assumed a role as one of the principal sources of foreign currency deposits in the country, possibly taking second place behind oil revenues, and topping remittances from migrants in the US.

The violent industry generated by migrants passing through Mexico on their way to the US, mainly Central Americans, is among the most alarming: kidnappings demanding huge ransoms, women captured by the cartels and sold to prostitution rings, or the bodies of migrants butchered to sell their organs.

Human trafficking is another of these lucrative businesses; in addition to the migrant trade, thousands of youths, adolescents, and even young girls are kidnapped and sold, many of them into prostitution. In the state of Mexico there are 400 disappeared teenagers between the ages of 12 and 17; many of them could have fallen into the clutches of sex slavery.

The Mexican drug lords are big capitalists who trade in a highly lucrative illegal product. Their businesses are extensive and are based on theft, the sale of human beings, robbery, and extortion. Some of them invest in legal businesses and appear in public as respectable entrepreneurs. In their areas of control, they impose their own business taxes, to allow working of the land, crossing their territory, etc. They have become a living nightmare for the population.

[to be continued...]