Eighty years ago, on 21st January 1924, Vladimir Illyich Ulyanov, the leader of the Russian Soviet state and Communist International died after a prolonged illness. He was fifty-three years of age. His life covers years of profound upheaval, crisis and transformation - the last quarter of the nineteenth century and the first quarter of the twentieth century - crowned by the First World War and the Russian Revolution of 1917. He was without doubt the greatest revolutionary of his time, a giant of a man, whose actions changed the course of history in the 20th Century. [This article was originally written in 2004]

The following is not a detailed account of Lenin's life; as such an enterprise would fill a large volume and more. Readers are invited to read or reread Alan Woods' book on Bolshevism and Ted Grant's book on Russia for a more detailed account. On this anniversary of his death, the intention of this piece is to briefly summarise the ideas and historical role of this great revolutionary Marxist. As such, it is a defence of Lenin - the revolutionary - against all the attacks and slanders that have poured down upon his name like a Niagara, in life as in death. This is no simple eulogy of a revolutionary hero; but has value only in so far as it assists us in understanding the real Lenin, his revolutionary contribution, as well as the tasks that lie before us in this present epoch of revolution and counter-revolution. Above all, its intention is to draw inspiration and knowledge for today's battles.

In reference to Marx, Lenin warned against those who, after his death, would blunt his revolutionary message:

"During the lifetime of great revolutionaries, the oppressing classes have invariably meted out to them relentless persecution, and received their teaching with the most savage hostility, most furious hatred, and a ruthless campaign of lies and slanders. After their death, however, attempts are usually made to turn them into harmless saints, canonising them, as it were, and investing their name with a certain halo by the way of ‘consolation'to the oppressed classes, and with the object of duping them; while at the same time emasculating and vulgarising the real essence of their revolutionary theories and blunting their revolutionary edge." (Lenin, The State and Revolution).

This was certainly the case with Lenin, whose ideas in the hands of the Stalinist reaction were cynically twisted to justify every counter-revolutionary policy of the Soviet bureaucracy. Much to the delight of the world bourgeoisie, the apologists of Stalinism shamefully mutilated the revolutionary essence of Lenin, turning it into its very opposite, in order to cover up their crimes against the working class. Thus bourgeois historians have always tried to falsely equate Stalinism with Leninism or Communism, in order to blacken the name of Lenin.

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin was born on the 10th April 1870, at Simbirsk on the Volga. He was the third of six children born into a well-to-do family. At this time, tsarist Russia was going through enormous transformations. The law of uneven and combined development revealed itself in its most glaring fashion as semi-feudal Russia copied the most advanced capitalist models already well established in Britain, Germany and France. In 1861 serfdom was abolished and new western influences were beginning to cause ferment within the Russian intelligentsia, long stifled by tsarist oppression. The Ulyanov family was caught up in this swirling current and was carried along in its wake. This was the period of the Narodnaya Volya or People's Will, a revolutionary idealist movement that sought to overthrow tsarism by individual terrorism. In 1881, they eventually succeeded in assassinating tsar Alexander II, the very success of which was to undermine the People's Will in the wave of savage oppression that ensued.

Lenin's eldest bother, Alexander, joined the Narodnaya Volya and directly participated in the attempted assassination of tsar Alexander III. He was caught and hanged with four others in May 1887. This personal tragedy had a major impact on the young Lenin, then aged seventeen. In the autumn of that year, he entered university at Kazan to study law. Shortly afterwards he was expelled for joining a student protest against the authorities, thus marking the beginning his revolutionary life.

Although Lenin had sympathies with his brother's views, he decided instead to join a Marxist circle in Kazan, where he studied Das Kapital and Anti-Duhring, among other things.

"Thanks to the emigration forced by the tsar, revolutionary Russia, in the second half of the nineteenth century, came into possession of rich international connections, and of an excellent grasp of the forms and theories of the revolutionary movement such as no other country had", wrote Lenin. (Lenin, Left-Wing Communism).

Lenin was by no means a fully-fledged Marxist at this time. His commitment to Marxism did not come easily. Not until 1891, after an intensive and detailed study of Marxist literature, did he become a convinced Marxist, and dedicated himself to the socialist revolution. He adopted a new vocation, the centre of his life, subordinating everything to this aim. He separated himself from his privileged background and came over whole-heartedly to the standpoint of the proletariat. This experience in the early revolutionary movement changed Lenin's entire life.

The new revolutionary ideas of Marxism confronted a whole series of confused tendencies of the surviving Narodniks (later to become the Social Revolutionaries) who idealised the peasantry, denied the necessity of Russian capitalist development and saw the village commune as the basis for socialism. As was seen, the Narodniks justified individual terrorism as a means of eradicating oppression. In contrast, Marxism saw the inevitable development of capitalism in Russia and with it the growth of its gravedigger in the form of the working class. As opposed to individual terror, the Marxists advanced the class struggle as the only revolutionary weapon that could overthrow the autocracy and bring about the socialist revolution. "Capitalism is going its way," wrote Plekhanov, the father of Russian Marxism, "it is ousting independent producers from their shaky positions and creating an army of workers in Russia by the same tested method as it has already practised ‘in the West'." However, even the Marxists were divided, with the appearance of a non-revolutionary legalistic type (Legal Marxism) led by Struve, which embraced Marx's economic analysis of capitalism but drew back from its revolutionary conclusions.

George Plekhanov, regarded as the founder of Russian Marxism, was originally an active member of the Narodniks. Disillusioned with the movement, he made contact with Frederick Engels and from then on became a convinced Marxist. Plekhanov founded the first Russian Marxist organisation – the Emancipation of Labour Group – in Geneva in 1883, and conducted a struggle not only against the Narodniks, but Bernstein's revisionism, and so-called "legal" Marxism, producing in the process many Marxist classics, especially on philosophy.

Lenin also threw himself into this struggle. Within Russia by 1895, his consistent work had borne fruit in the creation of the Union for the Struggle and Emancipation of the Working Class, a precursor of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. However, he was arrested by the authorities and after a year's imprisonment was exiled to Siberia for a further three years. It was under these underground conditions that he completed his classic work, The Development of Capitalism in Russia. Krupskaya, who had been a key political cadre in the Petersburg organisation, soon joined him in exile. From this time onwards, they worked closely together as comrades and companions until Lenin's death in 1924. "On the whole", recalled Krupskaya, "our exile was not so bad. Those were years of serious study."

By 1898 the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party was formed at its first congress in Minsk; but Lenin was still in exile. In any case, it was a short-lived affair as the congress was raided and nearly all its participants arrested.

At this time an opportunist revisionist tendency emerged within the Second International around the figure of Eduard Bernstein, a German Social Democrat. He attempted to revise Marxism, saying its theories were out of date and needed adapting to the new situation. Although Bernstein was defeated politically, this revisionist current arose within Russia under the guise of "Economism". This trend argued that politics was above the heads of the workers and the Social Democratic movement needed to concentrate on economic, day-to-day demands instead. Such an approach simply abandoned the political field to the rising bourgeoisie in their fight with the autocracy, leaving the working class to trail behind in its wake.

Lenin enthusiastically took up the struggle against "Economism", writing a series of articles that were finally published as a book in 1902 under the name of What is to be Done? This book however was not simply an argument against the "Economists", but was used by Lenin to develop his ideas on party organisation, especially the need to build a party based upon professional revolutionaries with an all-Russian central newspaper "as a collective agitator and organiser." The Russian Social Democratic Party was to be a disciplined party based upon democratic centralism, and modelled in reality on the German SPD. While the book contained a flaw about the working class only being able to achieve trade union consciousness, which was a mistake of Kautsky (and later repudiated by Lenin), it served to educate a whole generation of party activists and prepared the ground for the building of the Russian Social Democracy.

In particular Lenin laid heavy stress on the need for theory within the party. "Without revolutionary theory there can be no revolutionary movement", stated Lenin. He goes on to quote Engels concerning this point: "Let us quote what Engels said in 1874 concerning the significance of theory in the Social-Democratic movement. Engels recognises, not two forms of the great struggle of Social-Democracy (political and economic), as is the fashion among us, but three, placing the theoretical struggle on a par with the first two…

"‘The German workers have two important advantages over those of the rest of Europe. First, they belong to the most theoretical people of Europe; and they have retained that sense of theory which the so-called ‘educated'classes of Germany have almost completely lost. Without German philosophy, which preceded it, particularly of Hegel, German scientific socialism – the only scientific socialism that has ever existed – would never have come into being. Without a sense of theory among the workers, this scientific socialism would never have entered their flesh and blood as much as is the case. What an immeasurable advantage this is may be seen, on the one hand, from the indifference towards all theory, which is one of the main reasons why the English working-class movement crawls along so slowly in spite of the splendid organisation of individual unions…" (Lenin, What is to be Done?)

From December 1900 onwards, given the repression in Russia, the development of a party newspaper was undertaken abroad with the publication of the Iskra (Spark). As a mature 30-year old, Lenin moved to Munich to collaborate with Plekhanov and others to produce the paper. By 1902, it became too difficult to publish Iskra in Germany and the majority of the editorial board moved to London. Lenin and Krupskaya arrived in London in April to join Martov, Vera Zasulich and Potresov. Plekhanov and Axelrod, the other editors, remained in Switzerland, but came over to London for consultations. Issues 22 to 38 were edited in Clerkenwell Green, where Lenin shared an office with Henry Quelch, one of the leaders of the British Social Democratic Federation. The young Leon Trotsky, who was nicknamed the "Pen" for his fluent style, also came to London in October to join the other émigrés. As Krupskaya recalled in the first edition (1930) of her memoirs (and later expunged by the Stalinists), Lenin warmly welcomed Trotsky and insisted he become one of the contributors to Iskra. Within a few months, in March 1903, he proposed him for the editorial board.

At this time, preparations were soon in hand for the second congress of the RSDLP to be held in 1903. In reality it constituted the founding congress of the party and the drafting of its programme fell to Lenin. This congress met at first in Brussels, and hounded by the police, was forced to finish its proceedings in London. Out of some forty-four delegates representing twenty-six organisations, only four were actually workers. In the end, the supporters of the Iskra overwhelmingly outnumbered those of the "Economists" and the separatist Jewish Bund.

Ever since the first congress, the Bund had constituted itself as an autonomous section of the RSDLP. At the second congress they wanted to loosen their ties even further. As Krupskaya explained:

"The issue at stake was whether the country was to have a strong united workers' Party, rallying solidly around it the workers of all nationalities living on Russian territory, or whether it was to have several workers' parties constituted separately according to nationality. It was a question of achieving international solidarity within the country. The Iskra editorial board stood for international consolidation of the working class. The Bund stood for national separatism and merely friendly contractual relations between the national workers' parties of Russia." (Reminiscences of Lenin).

On this question, Iskra won a resounding victory for the unity of all workers within a single party.

However, late in the congress a deep split took place in the Iskra camp. The division between Bolshevik (majority) led by Lenin and Menshevik (minority) led by Martov developed over one clause in the statutes and the make up of the leading bodies! The paragraph offered by Lenin proposed that only those should be considered members of the party who "recognise the programme and support the party, not only financially, but by personal participation in one of its organisations". Martov wanted to substitute for "personal participation" the more "elastic" idea of "regular co-operation with" the party, "under the control" of one of its organisations. Lenin also wanted to reduce the editorial board of Iskra to three: consisting of Lenin, Martov and Plekhanov. Despite winning a majority, the split left Lenin isolated within the leadership after Plekhanov later sided with Martov. In the aftermath of this failed attempt to professionalise the party, Lenin resigned from the editorial board of Iskra and, suffering colossal strain, was close to a nervous breakdown.

There are many myths surrounding the second congress and the famous split. Firstly, it is claimed that Bolshevism emerged fully formed form this congress, and secondly, from then onwards the monolithic Bolshevik Party marched forward under Lenin's leadership to the successful conquest of power in October 1917. In fact, nothing could be further from the truth. The split in 1903 took place not over principles or fundamentals, but on secondary organisational questions. The later differences between these two tendencies were not at all clear in 1903, but only emerged over time, under the impact of events. The crucial political difference between Bolshevism and Menshevism – the attitude to the liberal bourgeoisie – only came to the fore in 1904. It was not until the 1905 Revolution that the lines became clear.

For the Mensheviks, the revolution facing Russia was to sweep away the remnants of feudalism and bring about conditions for the development of capitalism. It was a bourgeois-democratic revolution, as had taken place long ago in the west. The conditions for the socialist revolution were completely absent in Russia and, therefore, the task of the emerging working class was to subordinate itself to the bourgeoisie as the leader of the coming bourgeois-democratic revolution.

Lenin, while recognising the bourgeois-democratic nature of the revolution in Russia, nevertheless, drew fundamentally different conclusions. For him, the Russian liberal bourgeois had arrived too late on the stage of history and was organically linked to the autocracy. Consequently, the only role it was destined to play was a counter-revolutionary one. The only force capable of leading the revolution was an alliance between the proletariat and poor peasantry, leading to the establishment of a "democratic dictatorship of proletariat and peasantry". Furthermore, the fate of the Russian revolution would be linked to the successful socialist revolution in the west, which in turn would give an impetus to the revolution in Russia itself.

The real political differences now emerged where the Mensheviks became promoters of class collaboration resting on support for the bourgeoisie as opposed to the revolutionary masses. In truth, the split of 1903 was an anticipation of future political differences. Eventually, these differences would become a division between revolutionary socialism and reformism.

Trotsky in the end voted with the Mensheviks on organisational matters. He was later to admit his mistake honestly. He had not understood the real essence of the dispute and what Lenin was trying to build. In spite of this, on the political issues involved Trotsky agreed on all fundamentals with Lenin as opposed to the Mensheviks. In actual fact, Trotsky had an even clearer view of the social forces involved in the revolution than Lenin. Both agreed that the only revolutionary class capable of leading the revolution, a bourgeois-democratic one at that, was the proletariat in alliance with the poor peasantry. However, and this is where he differed from Lenin, having come to power, the working class would not stop at introducing bourgeois-democratic tasks, but would proceed to the socialist tasks, as part of the world socialist revolution.

Before 1917 Lenin had the perspective of the Russian revolution remaining within the confines of the bourgeois revolution. He linked the fate of the Russian revolution to the socialist revolution in the west. However, Trotsky believed the Russia proletariat could come to power before their brothers and sisters in Europe. It would be the beginning of the world socialist revolution, which is exactly what happened in 1917. This theory became known as Trotsky's Theory of Permanent Revolution. In 1917 Lenin had no problem in accepting the reality of the situation and saw from the way things had developed that perspective was indeed that of the socialist revolution.

The 9th January massacre in Petersburg provoked the 1905 revolution in Russia. The revolutionary events of that year were to confirm the counter-revolutionary actions of the liberal bourgeois, and firmly confirmed the independent revolutionary role of the young working class. During the course of the revolution, the workers spontaneously set up their own organs of struggle in the form of soviets, or Councils of Workers' Deputies, the embryo of workers' power. In the course of twelve months, the movement encompassed a whole spectrum of struggle: from petition to strikes, general strikes and insurrection. Such was Trotsky's role in the events that he was elected the president of the Petrograd Soviet, which led the general strike in October. However, after the defeated December Moscow uprising, the revolutionary movement went into decline as the government brutally reasserted its authority. Nevertheless, Lenin hailed the 1905 Revolution as a "dress rehearsal". Without this experience, in all probability the October Revolution of 1917 would not have been possible.

Within a few years, a bloody reaction had set in. Lenin, who had returned to Russia in November 1905, was once again forced into exile by 1907. The period of reaction brought many difficulties in its wake, where many revolutionary fighters, driven underground, lost heart and dropped out of the movement altogether. "They were difficult times", states Krupskaya. "In Russia the organisations were going to pieces." While the Mensheviks were affected by moves to "liquidate" the illegal party and concentrate all their efforts on legal open work, which under the prevailing reaction meant a rejection of revolutionary activity, the Bolsheviks were affected by ultra-left and sectarian tendencies, wishing to boycott legal avenues altogether, which again meant an abandonment of revolutionary work. Others became mired in philosophical idealism to which Lenin responded with a brilliant defence of dialectical materialism in his book Materialism and Empiro-Criticism (1908), which remains a classic philosophical work.

Once again, Lenin was forced to rely upon a small handful of people in exile and to conduct a struggle against "liquidationism" from both the right and left. Even then, work seemed dominated by petty strife and the squabbles of emigrant life. Shortly after the defeat of 1905, the Bolshevik organisation within Russia was reduced to a small shell. They had no alternative but to collaborate with the Mensheviks, bringing out a joint newspaper called Sotsial-Demokrat with Martov as editor, but is was not to last.

"In 1910", recalls Trotsky, "in the whole country there were a few dozen people. Some were in Siberia. But they were not organised. The people whom Lenin could reach by correspondence or by agent numbered about 30 or 40 at most."

Throughout the reaction Lenin attempted to keep the Bolsheviks on the correct path by combating the various ultra-left tendencies that affected them. Such firmness inevitably led to splits, especially with the boycottists (Otzovists). Yet generally speaking, Lenin's method was always flexible on tactics and organisational questions, but firm on principles.

By the end of 1910 a new revolutionary upsurge had begun in Russia that would last until the outbreak of world war in August 1914. By 1912, the split between the Mensheviks and Bolsheviks had assumed an open breach with the establishment of two separate parties. At this time, the Bolsheviks launched a new daily paper called Pravda, and within two years, and after consistent work, had won over four-fifths of the organised workers to their side. In the rigged Duma elections they had managed to win six deputies, all of whom were arrested at the outbreak of war.

The world war of 1914-18 proved to be a turning point. It demonstrated that capitalism had exhausted itself and its contradictions had reached explosive levels. The development of the productive forces was being strangled within the straightjacket of private ownership and the nation state. The test of war, and there could be no greater test, found the leaders of the Second International wanting. In August 1914, they betrayed the working class and discredited international socialism by siding with their own capitalists. As the Social Democratic leaders voted for the war credits of their own ruling class, they called upon the workers to slaughter one another in the name of "justice". Despite their original declared opposition to war, when the time came they capitulated. The workers were shocked. Even Lenin thought the declaration supporting the war published in the German Social Democratic paper was a forgery! In reality, the Second International had suffered an ignominious collapse. In the words of Rosa Luxemburg, it had become "a stinking corpse".

Only the Russian and Serbian parties stood by the line of socialist internationalism. The Bolshevik deputies in the Duma voted against the credits and were deported to Siberia. In December 1914, Karl Liebkneckt voted against the war credits in Germany. It was left to the tiny handful of internationalists worldwide, persecuted and isolated, to become the leadership for rebuilding the forces of international socialism.

From exile in Switzerland Lenin addressed the class-conscious workers disoriented by the great betrayal. He characterises the world war as a reactionary imperialist war, which was led by the main imperialist powers of finance-capital for world plunder, markets, spheres of influence and profits. In this explanation, he sharply distinguished between those progressive wars of social and national liberation waged by oppressed classes and nations, which had the support of socialists. This imperialist war was of a fundamentally different character, said Lenin, and called upon the working class to "transform the imperialist war into a civil war", into a war to overthrow capitalism and for the victory of socialism. The workers had no fatherland, to quote Marx. The test of a sincere struggle against imperialism was a fight against one's own imperialist government. Lenin linked this analysis with a courageous call for a new Third International to maintain the spotless banner of international socialism. The international gatherings at Zimmerwald (1915) and Kienthal (1916) provided a vital focal point for the left internationalists, which was finally to lead to the founding of the Third (Communist) International in March 1919.

During the war years, Lenin spent a great amount of time making a fresh study of Marxist theory. In particular, he gathered material on economic questions that were used to produce his classic pamphlet Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (1916). He also engaged in a thorough study of dialectical materialism and philosophy, a continuation of his studies of 1908-1909. Above all, he poured over Hegel's Science of Logic, in order to elaborate Marx's dialectical method. The mastering of dialectical materialism, the Marxist world outlook, was essential in understanding the complex unfolding of events. "The decisive thing in Marxism", declared Lenin, "is its revolutionary dialectic."

Lenin understood that the experience of war was inevitably preparing new revolutionary waves. The crisis eventually broke in Russia in February 1917, the "weakest link" in the chain of world capitalism. On international women's day, workers of Petrograd struck work and demonstrated on the streets under the slogans "Down with the war!", "Down with Tsarism!" and "Give us Bread!" These protests and strikes grew into a revolution, which brought down the 1,000-year edifice of tsarism. As in 1905, soviets were thrown up alongside a provisional government, constituting a regime of "dual power", but were initially dominated by reformist parties, the Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries. The latter parties had no perspective of taking power from the bourgeoisie. The revolution had placed power into the hands of those who had carried out the revolution, the workers and soldiers, but they were not conscious of this power, which was handed over to the reformist leaders, who in turn handed it to the bourgeois government under Price Lvov. Such a situation of "dual power" could not last indefinitely: either the soviets would assume complete control, or there would be complete counter-revolution.

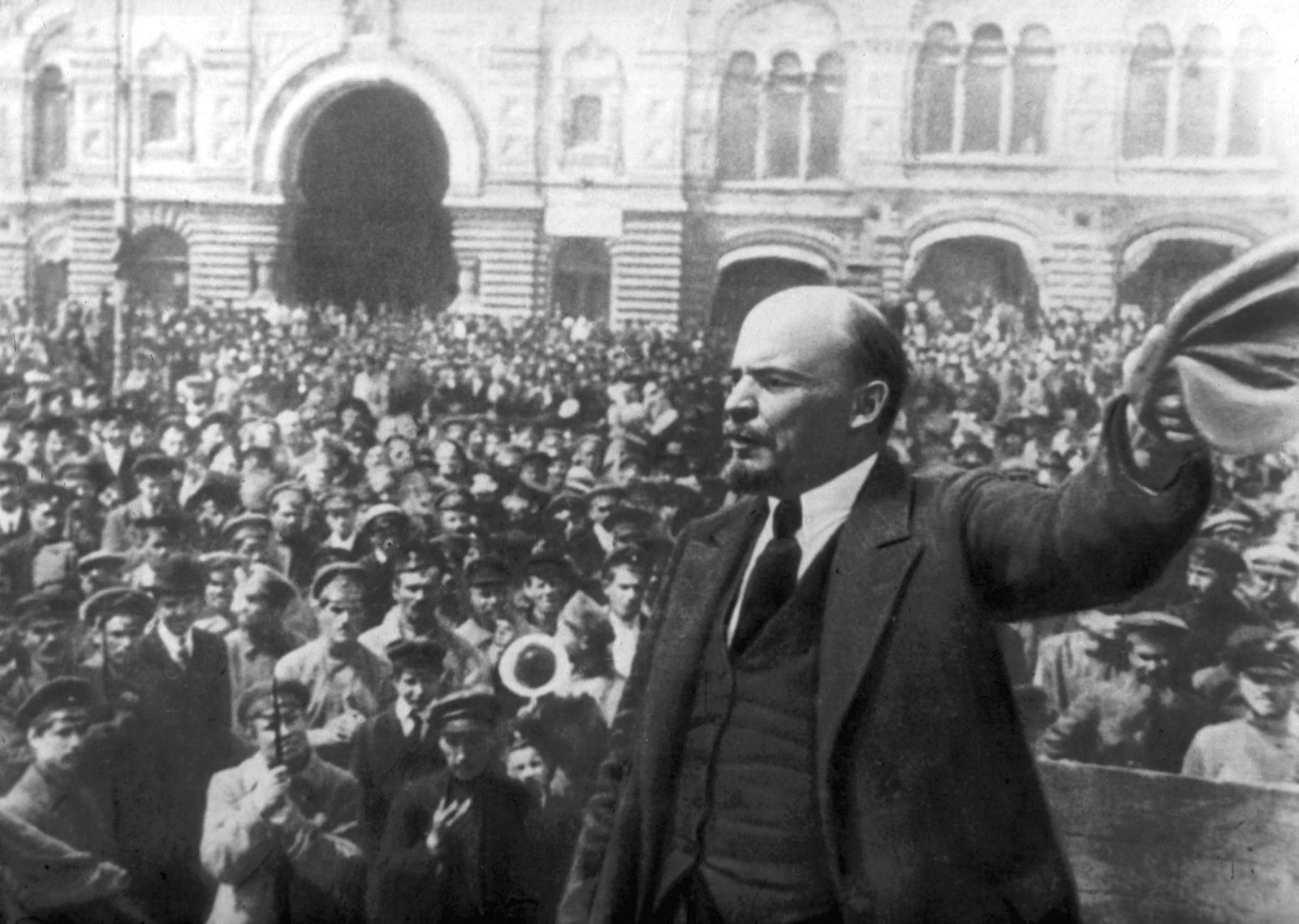

Within a matter of months after leaving his exile in Zurich, Lenin was to become "the most hated and most loved man on earth." It took a further eight months from the first revolution, with sharp turns and the rapid unfolding of the class struggle between revolution and counter-revolution, for the workers to finally become conscious of their strength and take power and organise a Soviet Republic under the leadership of the Bolsheviks.

Of course this was no easy matter. When Lenin arrived at the Finland Station in Petrograd on 3rd April, he greeted the mass crowds with the words: "Long live the world socialist revolution!" He had no trust in the Provisional government, which the editors of Pravda (Kamenev and Stalin) had duly granted. He chastised them and set about conquering his own party for the immediate perspective of socialist revolution. In his famous Letters from Afar, written at the time, he had already defined the key tasks:

"(1) To find the surest road leading to the next stage of the revolution or to the second revolution, which revolution (2) shall transfer the state power from the government of landowners and capitalists (the Guchkovs, Lvovs, Miliukovs, Kerenskys) to a government of the workers and poor peasants. (3) The latter government must be organised on the model of the Soviet of Workers' and Peasants' Deputies."

Lenin had to wage a bitter struggle to overcome the initial resistance amongst the "Old Bolsheviks" and set the Bolshevik Party on a course to win over the masses and towards a second revolution. While the Bolsheviks were a minority, their key task was to "patiently explain" their policies to the mass of workers. Finally, on the basis of events, they succeeded in winning a majority under the slogans, "Bread", "Land" and "Peace". Lenin's writings in this period constitute a profound body of knowledge for Marxists of leadership in the midst of a revolution and of the art of insurrection. In the midst of these historic events, he completed one of his most important theoretical works, The State and Revolution, clarifying the line on this vital question between reformism and revolution.

By the beginning of September the Bolsheviks had won a majority in the Petrograd and Moscow soviets. On 25th October, the old regime was swept away and a Soviet government, composed of Bolsheviks and Left Social Revolutionaries, was established with Lenin as President and Trotsky as Foreign Minister, or Peoples' Commissars, to use the new terminology. The history of the world began to dramatically change.

Lenin's individual role in 1917 was crucial, and serves to highlight the vital role, under certain circumstances, of the individual in history. In the broad sweep of historical events, individuals generally play a secondary role. However, there are crucial times, especially when a situation is on a knife-edge, when individuals can play a decisive role for better or worse. Lenin proved indispensable. He integrated himself into the course of events, grasping their underlying laws, and shaping the social forces that were to carry through the revolution. Trotsky summed up this experience in reviewing his own role in 1917:

"For the sake of clarity I would put it this way. Had I not been present in 1917 in Petersburg, the October Revolution would still have taken place – on the condition that Lenin was present and in command. If neither Lenin nor I had been present in Petersburg, there would have been no October Revolution: the leadership of the Bolshevik Party would have prevented it from occurring – of this I have not the slightest doubt!" (Diary in Exile 1935).

This was undoubtedly true. The resistance of the party heads to the new course was very strong. Without Lenin it would have been infinitely stronger. Single-handedly, Trotsky believed he personally might have lacked the necessary authority to turn the situation around. Under these circumstances, the Bolshevik Party would have failed to adopt the necessary road to power in time. This could possibly have allowed the bourgeoisie to surrender Petrograd to the Germans, put down the leaderless proletarian uprising and install its authority under a military-Bonapartist regime. The entire course of history would have been different, with future historians ridiculing the utopian antics of the Bolsheviks!

Trotsky, who had remained outside both Bolshevik and Menshevik camps, had finally recognised his mistake in attempting to unify both factions. On his return to Russia in 1917 he joined the Bolsheviks and was elected to its leadership. Looking back two years after the success of the revolution, Lenin wrote: "At the moment when it seized the power and created the Soviet republic, Bolshevism drew to itself all the best elements in the currents of socialist thought that were nearest to it." Without doubt this referred to Trotsky, who, as head of the Petrograd Soviet and Revolutionary Military Committee, commanded the technical/military preparations of the successful October Revolution. In fact in these years Lenin's reliance on Trotsky, the co-leader of the Revolution, was enormous. Throughout this time the names of Lenin and Trotsky were inseparable. "If we are killed," once asked Lenin of Trotsky, "do you think Bukharin and Sverdlov will manage?" This was no passing concern as the fate of the Revolution was frequently in the balance.

At the beginning of the civil war, the Social Revolutionaries went over to the counter-revolution and attempted to murder the Bolshevik leaders. On 30th August 1918, Lenin was shot and wounded by the bullet of a Left Social Revolutionary. Although he managed to recover and resume work, this injury was in large measure responsible for his premature death some five years later. Bombs were also planted to blow up Trotsky's red train, but he managed to escape by chance.

The victory of the October Revolution transformed the world situation. For the first time in history, the working class had conquered power and established proletarian rule. The tasks facing Lenin and the Soviet regime were to achieve peace, consolidate the regime and extend the socialist revolution worldwide. The Soviet Republic however faced ever-greater dangers. The international bourgeoisie immediately set to work in destroying the Bolshevik regime by aiding internal counter-revolution and despatching twenty-one imperialist armies of intervention. Under the command of Trotsky, the mighty Red Army of five million was constructed to repel the foreign invasion and defeat the internal White Armies.

During the momentous years of 1917-1923, Lenin concentrated his entire being on the burning questions of defence and world revolution. The work of Lenin during this time outstrips any summary biography. It ranges over the field of world politics, civil war, the new economic order, the building of the Communist International, and the struggle against bureaucracy. Alongside the host of speeches and reports he gave, he also found time to write such Marxist classics as Left-Wing Communism, an Infantile Disorder, and Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky.

By late 1920, with the routing of Wrangel's white army, the counter-revolutionary and interventionist forces were all but defeated. The Soviet state had won a reprieve at terrible cost. This respite gave way to a temporary "equilibrium" between the powers, which was used by the Bolsheviks to prepare the working class internationally for the new revolutionary wave. "A balance has been attained", stated Lenin, "a highly unstable one, but certainly a balance. Will it last long? I don't know; nor do I think anyone can tell. We must, therefore, show the greatest possible wariness."

Unfortunately, with the Russian economy shattered and the world revolution delayed, the Soviet state suffered from an internal degeneration characterised by the growth of a bureaucratic cancer within the state and party. With each demoralising defeat and setback for the exhausted Russian masses, the bureaucrats pushed aside the workers and placed themselves increasingly in control. Inevitably this bureaucratic reaction surfaced within the Bolshevik Party itself and was reflected in the figure of Stalin. After the death of Lenin, this parasitic growth on the back of the workers' state was to eventually lead to the political dispossession of the working class and the creation of the totalitarian regime under Stalin.

From the end of 1922 onwards, Lenin's last life and death struggle was against this bureaucratic degeneration. Unfortunately, Lenin's first stroke came in the spring of 1922, resulting in paralysis in his right arm and leg. After convalescing, he managed to recover and returned to work later in the year. In December, came a second stoke, this time more severe. From his death-bed Lenin was preparing a blow against Stalin and his allies, who were busy scheming against Trotsky. "Vladimir Ilyich is preparing a bomb for Stalin at the congress", relates his secretary Fotiyeva. As part of this he formed a secret bloc with Trotsky against Stalin over the Georgian Affair and other key questions. Finally, in Lenin's Testament written 24/25th December, with a postscript added on 4th January 1923, Lenin urges the removal of Stalin as General Secretary of the Party. Two months later, he breaks off all personal relations with Stalin, and publishes his famous article Better Fewer, but Better, containing a vitriolic attack against the Workers' and Peasants' Inspectorate (Rabkrin), headed by Stalin. "We have bureaucratism not only in the Soviet institutions but also in the party", stated Lenin. Whilst waiting for a reply to a note from Stalin, Lenin suffered his third deadly stroke and lost the power of speech. Despite a late rally in his health, he finally died of a brain hemorrhage in January 1924.

Stalin suppressed Lenin's Testament. Behind the scenes, he had developed a tight grip over the party apparatus. Assisted by Lenin's death and the isolation of the revolution, Stalin worked to concentrate power into his hands. Part and parcel of this was the expulsion of Trotsky's Left Opposition. Under Stalin's rule, a political counter-revolution, based upon nationalised property rights, was carried through in the Soviet Union by the mid-1930s. The Purge Trials constituted a river of blood that separated the regimes of Lenin and Stalin.

Trotsky's real relationship with Lenin was best summed up in a letter sent by Krupskaya the week after Lenin died:

Dear Leon Davidovich,

I write to tell you that about a month before his death Vladimir Ilyich, looking over your book, stopped at the place where you give a characterisation of Marx and Lenin, asked me to re-read it, listened very attentively, and then read it over again himself.

And here is what I want to say besides: The relation which was formed between Vladimir Ilyich and you, when you came to us in London from Siberia, never changed with him to his very death.

I wish you, Leon Davidovich, strength and health, and I embrace you.

N. Krupskaya.

As early as 1926, Krupskaya stated in a circle of the Left Opposition: "If Ilyich were alive, he would probably already be in prison." Later, the Stalinist bureaucracy would conquer more than the Opposition. It would conquer the Bolshevik Party. It would defeat the programme of Lenin.

Lenin, without doubt, was a political giant of a man. He was the most outstanding revolutionary of the twentieth century. Imbued with confidence in the final victory of the working class, he was a revolutionary and Marxist to his very being. However, Lenin was not born with these qualities, but made himself through a combination of learning and experience, of theory and practise. By the age of 23, all the fundamental features of Lenin's personality, his outlook on life, and his mode of action were already formed. He lived and breathed the revolution. Through this greatest of historical tasks and singleness of purpose, he fulfilled himself completely and absolutely. Through years of study in the fundamental ideas of Marxism combined with hard practise, he became Lenin, the great man and teacher we know.

In the broad sense, after the death of Marx and Engels, the defence of genuine Marxism fell to Ilyich Lenin. Through his boundless work and confidence, he prepared the way for the first successful socialist revolution, and changed the course of world history.

"Only the proletarian socialist revolution can lead humanity out of the blind alley created by imperialism and imperialist wars", wrote Lenin. "Whatever difficulties, possible temporary reverses, and waves of counter-revolution the revolution may encounter, the final victory of the proletariat is certain."

Individuals of Lenin's standing are rare in the revolutionary movement. This article does not challenge each of us to become a Lenin or a Marx. We must be ourselves. However, it is nevertheless a challenge to change ourselves, to develop ourselves theoretically and politically for the role we will play in the future. We are proud to stand on the shoulders of the great Marxists that went before us. We, like them, must imbue ourselves with a sense of history and a faith in the classless future of mankind.

With Lenin's death, the defence and continuity of Marxism fell on the shoulders of Leon Trotsky who fought against the Stalinist epigones. Today, that continuity falls on the present generation of Marxists, in conditions of deepening world crisis and instability, to carry forward this fight for a new era of humanity, to the final victory, which it was Lenin's triumph to inaugurate, but which he could not live to complete.