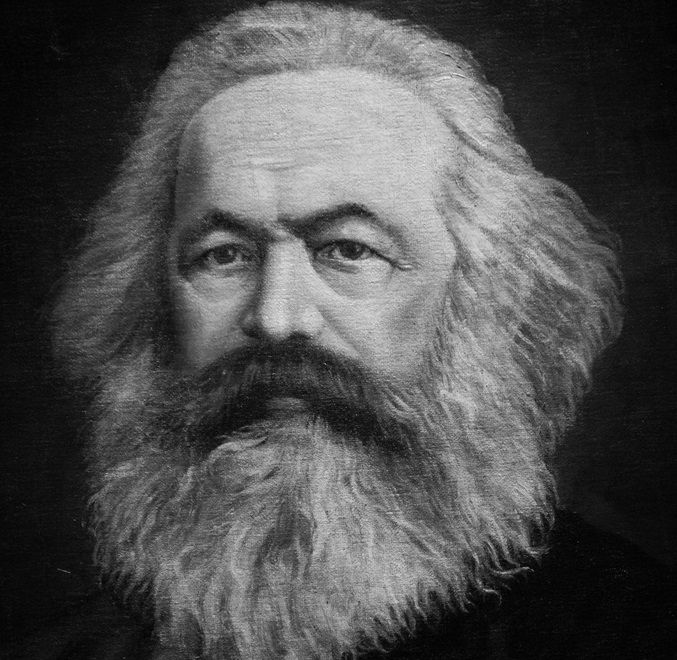

One hundred and twenty years ago - on March 14 1883 to be precise - Karl Marx, one of the greatest figures in human history, died. Despite over a century of attacks, distortions and attempts to belittle Marx's contribution, no-one can doubt that he dramatically altered the course of human history.

"Philosophers have only interpreted the world in different ways. The point is, however, to change it." - Karl Marx

One hundred and twenty years ago - on March 14 1883 to be precise - Karl Marx, one of the greatest figures in human history, died. In an online poll conducted by the BBC a couple of years ago Marx was voted the greatest thinker of all time. Despite over a century of attacks, distortions and attempts to belittle Marx's contribution, no-one can doubt that he dramatically altered the course of human history. That would be reason enough to study Marx's ideas and his writings, whether one agrees or disagrees with them.

For those workers and youth who wish to struggle to change society however, there is an even more pressing reason to study Marxism. On reading Marx's writings on philosophy, history, economics, and sociology, one is struck not only by their remarkable breadth and depth, but above all by their relevance to the world today. These writings are an invaluable weapon in the hands of workers and youth everywhere fighting for the socialist transformation of society.

During the course of 2003 we intend to produce a series of articles on the writings of Marx. These are not meant to be a substitute for the real thing, but are intended to whet the readers' appetite to plunge more fully into a study of Marx's writings and ideas. A word of warning here. Libraries and bookshops the world over are littered with learned tomes 'about Marxism'. In reality these are usually 'against Marxism', but few are honest enough to admit it. These works fall into two main categories. First the method of knocking down a straw man, that is, spurious arguments that have nothing to do with Marxism are presented as the ideas of Marx only to be easily countered and defeated. Secondly there are the 'interpretations', that is works that go to great lengths to tell us 'what Marx really meant', when in fact they proceed to distort Marx's ideas out of all recognition. To discover what Marx meant is in reality quite easy. All one has to do is read the books he wrote.

Some people will tell you that those books are very difficult to read. This is not really true. Marx wrote in such a way that the average person could understand him. He wrote essentially for the workers. Having said that Marx did not believe in what the BBC call 'dumbing down', that is talking to the workers as if they were little children. As every worker knows nothing worth having in this life is achieved without a struggle. To study Marx's writings with the necessary attention undoubtedly requires a certain amount of work. The rewards however merit such effort.

Marx wrote not just about politics and economics for which he is perhaps most widely known, but also about philosophy, art, history, science, and all questions relating to human society. Marx declared once that his favourite maxim was that of the Roman general and poet Terence "Nihil humani a me alienum putu. " (Nothing human is alien to me).

The advanced worker must make it his or her duty to make a thorough study of Marx's writings, to master the method of Marx. This is not an academic exercise. Marx's ideas are above all a guide to action, they provide a method for understanding the world, the better to be able to change it.

Marx was born 185 years ago, on May 5, 1818, in the city of Trier in Rheinish Prussia. His father was a lawyer and his family was comfortably well-off. They were not particularly revolutionary in their outlook. After leaving school in Trier, Marx went on to university first in Bonn and then later in Berlin, where he read law, majoring in history and philosophy. As a student Marx was a follower of the great German philosopher Hegel's ideas. In Berlin, he belonged to a group of "Left Hegelians" who sought to draw atheistic and revolutionary conclusions from Hegel's philosophy.

After graduating from university, Marx moved to Bonn, hoping to become a professor. However, the reactionary policy of the government, which deprived Ludwig Feuerbach of his academic position in 1832, led Marx to abandon the idea of such a career. At this time Left Hegelian views were making rapid headway in Germany. Feuerbach, in particular, developed a criticism of theology and began to develop materialist ideas. The ideas of Feuerbach had a profound effect on Marx and the other Left Hegelians of the day. The year 1843 saw the appearance of his book Principles of the Philosophy of the Future. "We all became at once Feuerbachians", Engels wrote some years later. It was around this time that a radical group in the Rhineland, who were in touch with the Left Hegelians, founded an opposition newspaper called Rheinische Zeitung in Cologne. The first issue appeared on January 1, 1842, and in October 1842 Marx became its editor-in-chief and moved from Bonn to Cologne.

The paper had begun with a revolutionary-democratic outlook and this became more and more pronounced under Marx's direction. As a consequence the government imposed a series of censorship measures against the paper, and then on January 1 1843 decided to suppress it altogether. The Rheinische Zeitung suspended publication in March 1843.

This was the year in which Marx married. His wife came from a reactionary family of the Prussian nobility, her elder brother later became Prussia's Minister of the Interior during a most reactionary period between 1850 and 1858.

In the autumn of 1843, Marx moved to Paris in order to publish a radical journal abroad, together with Arnold Ruge. However only one issue of this journal, Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher, appeared. Publication was discontinued owing mainly to the difficulty of secretly distributing it in Germany, and to disagreements with Ruge.

In September 1844, Frederick Engels came to Paris for a few days, and from that time on became Marx's closest friend and political collaborator. The names Marx and Engels have since become inseparable, almost one person. Immediately the two men proceeded to take a most active part in the hectic life of the revolutionary groups in Paris. Proudhon's anarchist ideas were quite popular amongst some of these groups. Marx answered them thoroughly an meticulously in his Poverty of Philosophy, in 1847, using the method which one finds time and again in the writings of Marx, withering criticism backed up by facts, and substantial quotations from the writings of those he criticises. Unfortunately this rigorous and honest approach has not been shared by that countless number who have written spurious works in an attempt to rubbish Marx's ideas ever since.

Marx and Engels together waged an energetic struggle against the various doctrines of petty-bourgeois socialism, anarchism and so on, in an effort to place the ideas of socialism on a scientific footing. This was perhaps Marx and Engels' greatest achievement, to pull the idea of socialism down from the stratosphere to earth and the real world of class society. Socialism was no longer to be just a lofty ideal, but the product of a material struggle between the classes, a product of historical development. The ideas of Marx and Engels are scientific socialism.

Marxism is a science. In order to understand the problems of the modern world, a scientific method is necessary. The bourgeoisie and its academic experts are at a loss to explain what is happening in the world. One would look in vain in the pages of the economic journals for a rational explanation of the world crisis of their system. As for sociology, philosophy, psychology etc. – they write a great deal and yet they say nothing. Whilst in its progressive phase the bourgeoisie produced great ideas, now in its senile decay, it produces only gibberish.

On the one hand it fell to Marx, and his great co-thinker and lifetime comrade, Frederick Engels, to place the ideas of socialism on a sound scientific basis linked to an understanding of the class nature of society. At the same time their task was to provide the working class with the ideological weapons it requires to change society. For without a scientific understanding of the world it is impossible to change it.

These revolutionary ideas inevitably drew the attention of the authorities, already shaken by the onward march of revolt across Europe. At the insistent request of the Prussian government, Marx was banished from Paris in 1845, as a dangerous revolutionary. He went to Brussels. In the spring of 1847 Marx and Engels joined a secret propaganda society called the Communist League. They took a prominent part in the League's Second Congress in London in November 1847. As a result they were charged with drawing up the document which became The Communist Manifesto.

The Communist Manifesto, written when Marx and Engels were still young men, is a truly remarkable document. Its publication represents a turning point in history. It is as fresh today as when it was first written in 1848, if anything it is probably more relevant now than when it was then. In the pages of the Manifesto it is possible to see the superiority of Marx's method very easily. Take a look at any book written by the bourgeois 150 years ago. Today it will be just a curiosity. But if you read the Manifesto, you will find an accurate description of the world, not as it was in 1848, but as it is now. Phenomena such as globalisation, the concentration of capital, the exploitation of labour under the guise of modern technology – all these things were not only predicted by Marx but explained scientifically.

This is not the place to look at the Manifesto in detail, that will be the subject of a later article. We cannot pass it by completely, however. Not even the bourgeois do that, indeed, some of them have even been forced to admit, grudgingly, that at least in places, Marx was right:

"As a prophet of socialism Marx may be kaput; but as a prophet of the 'universal interdependence of nations' as he called globalisation, he can still seem startlingly relevant... his description of globalisation remains as sharp today as it was 150 years ago" write John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge of The Economist, in their book A Future Perfect: The Challenge and Hidden Promise of Globalisation

Indeed on reading the Communist Manifesto today one is amazed at how contemporary Marx's words appear. Not just the growth and interdependence of the world market is predicted here,

"In place of the old local and national seclusion and self-sufficiency, we have intercourse in every direction, universal interdependence of nations." But also the domination of that market by a handful of monopolies and the centralisation and concentration of capital that this represents: "It has agglomerated population, centralised the means of production, and has concentrated property in a few hands."

The reduction of the workforce to the role of slaves to the machine, "in proportion as the use of machinery and division of labour increases in the same proportion the burden of toil also increases, whether by prolongation of the working hours, by the increase of the work exacted in a given time, or by increased speed of machinery,"

More importantly we find the reason for these developments, the contradiction between the expansion of the forces of production and the narrow limits imposed by the twin straitjackets of capitalism - the private ownership of the means of production and the borders of nation states, "The conditions of bourgeois society are too narrow to comprise the wealth created by them."

Of course those bourgeois who concede that Marx was right here or there write to bury him not to praise him. Inevitably they conclude "obviously socialism failed." However such an off the cuff, unsubstantiated assertion will not fool the new generation of workers and youth who are discovering the ideas of Marxism in their search for a solution and a future. Whilst it remains true, and a crime of truly historic proportions, that Stalinism dragged the names of Marx and Lenin through the mud, the accomplishments of capital to date in Russia and Eastern Europe are hardly inspirational. The restoration of the free market has brought not prosperity but prostitution, profits for the few but misery for the many. This is not to defend or justify the crimes of Stalinism. On the contrary, the disaster in Russia today should clarify that it was not the absence of the market that was the problem but the lack of democracy. It was not the nationalised economy but the suffocating, dead weight of bureaucracy and corruption which strangled the Soviet Union. The one element of the October revolution remaining, that is the one connection with the ideas of Marx, albeit in a barely recognisable, perverted form, namely a state owned economy, enabled Russia to develop from a backward country to the second power on the planet. However the monstrous bureaucracy and its totalitarian dictatorship which leeched off the lifeblood of the planned economy doomed it. To excuse their bureaucratic excesses Stalin twisted Marx's aphorism "from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs" into "from each according to his ability, to each according to his work." Of course the "work" of the bureaucrats was so onerous that they required higher wages, perks etc. In the same way the pig Napoleon in Orwell's Animal Farm rewrote the teachings of Major.

Without democracy, control over all aspects of society by the working class, socialism was never created in Russia. It speaks volumes that in addition to their many crimes the Soviet bureaucracy with the immense resources of a sixth of the planet at their disposal came up with not one single original thought. Compare that to the accomplishments of the poverty stricken Karl Marx.

The Soviet bureaucracy however was concerned only with their own survival and the survival of their privileges. They developed not one new idea, instead they attempt now to turn the clock back by restoring capitalism. What we saw in Russia was not socialism. Socialism could never be built within the confines of a single country, even one the size of Russia.

Today's new generation discovering Marxism will see this easily enough. Even now in their newfound appreciation of some of Marx's conclusions these learned bourgeois academics are unable to take the next logical step and ask why Marx came to correct conclusions. This is not a question the bourgeois are keen to answer. If on not one, or two, but many occasions a method leads to correct conclusions it would seem reasonable to assume that the theory used was correct. A 'lucky guess' is not likely to be repeated often. Yet the prediction of the development of the world market does not drive them to read more of Marx or to accept that not only his conclusions but also his method was and remains correct. Such keen insights were not simply a work of intuitive genius - though there is no doubt that Marx and Engels stood head and shoulders above our modern day intellectual giants. Marx's ideas represented everything that was best in the achievements of the bourgeoisie, bringing together the best of English political economy, French sociology and German philosophy. From this new height they were able to see far indeed.

Their method was their great accomplishment. Using it we can understand the world around us and offer a way out of crisis ridden capitalism. That is why the dreaded question 'Why was Marx right?' is one the bourgeois refuse to address. Fortunately Marx's ideas are not meant simply to convince the bourgeoisie to change their tune. That would be utopian. Marxism instead has the goal of arming the working class and the youth for the revolutionary struggle needed to change society.

In 1848, as Marx explained, the spectre of revolution was haunting Europe. The power of Marx's ideas led the ruling class to expel him from one country after another. On the outbreak of the Revolution of February 1848, Marx was banished from Belgium. He returned to Paris and then, after the March Revolution, he went to Cologne, Germany, where Neue Rheinische Zeitung was published from June 1 1848 to May 19 1849, with Marx as editor-in-chief. His ideas were being daily confirmed by the course of the revolutionary events of 1848-49. The victorious counter-revolution instigated court proceedings against Marx. He was acquitted on February 9 1849 but then banished from Germany on May 16 1849. From Germany Marx travelled on to Paris, was again banished after the demonstration of June 13, 1849, and then went to London, where he lived until his death.

His life as a political exile was a very hard one, as the correspondence between Marx and Engels clearly reveals. Poverty weighed heavily on Marx and his family; had it not been for Engels' constant and selfless financial aid, Marx would not only have been unable to complete Capital but would have inevitably have been crushed by want.

Capital, completed after Marx's death in the main due to the tireless efforts of his comrade Engels, is probably the best known of Marx's writings. In these three volumes, which represent capitalism's genome, there is more than enough argument to convince a thinking bourgeois of the inability of the capitalist system to solve its inherent problems.

Yet today's thinking bourgeois are not studying how society or economy works. They are thinking about how to defend their system and their privileged position. They think not of how new technology can be used to shorten working hours to allow us time to participate in decision making and implementation. Instead they research how to use new technology to squeeze an ounce more out of our muscles and brains in the name of profit.

They don't investigate the worldwide eradication of disease through the knowledge contained in the Human Genome, they calculate how to patent chromosomes and medicines to profit from our ill health.

A small layer of scientists, and intellectuals in different fields can no doubt be won over to socialism, but society cannot be changed simply by changing the minds of the ruling class one by one. Marxism came into being as an attempt to place socialism on a scientific footing, to rescue it from the genius but idealistic utopians of earlier generations who believed that socialism could be achieved simply by demonstrating its intellectual superiority.

Nonetheless the intellectual struggle, the struggle over ideas, was for Marx of decisive importance. First and foremost he recognised the power of ideas "We are firmly convinced" he wrote "that the real danger lies not in practical attempts but in the theoretical elaboration of communist ideas, for practical attempts, even mass attempts, can be answered by cannon as soon as they become dangerous whereas ideas which have conquered our intellect and taken possession of our minds... are demons which human beings can only vanquish only by submitting to them."

The revival of the democratic movements in the late fifties and in the sixties recalled Marx to practical activity. There is a myth that Marx was a writer and thinker, but not a practical revolutionary. This is nonsense. For Marx theory was a guide to action, above all the revolutionary action of the proletariat. Marx had played an active and leading role in the movement in Germany and France. Now in London in 1864, on September 28, the International Working Men's Association - the celebrated First International - was founded. Marx was the heart and soul of this organisation, the author of its first Address and of a host of resolutions, declaration and manifestoes.

Marx's health was undermined by his strenuous work in the International and his still more strenuous theoretical studies and writing. He continued to work tirelessly on the question of political economy and on the completion of Capital, for which he collected a mass of new material and studied a number of languages including Russian.

On December 2 1881 Marx's wife died, and then on March 14 1883 Marx himself passed away peacefully in his armchair. He lies buried next to his wife at Highgate Cemetery in London.

Marx died 120 years ago. But his ideas live on to educate and inspire a new generation of class fighters all over the world. We dedicate our struggles to the memory of this great revolutionary figure. In recent years many a learned wiseacre has declared that struggle to be finished. Yet for all their scribblings the spectre of revolution is once again aboard. This time that spectre casts its shadow over not just Europe but the whole world. The struggle is far from finished, in fact it will continue until humanity finally triumphs over all obstacles and raises itself up to its true height. For thousands of years, knowledge and culture have been the monopoly of a tiny handful of wealthy exploiters, who have used and abused their monopoly to keep millions of their fellow men and women in chains. Socialism will put an end to this odious monopoly once and for all, giving free access to the wonders of culture to every man, woman and child on the planet. It was Marx who declared, "workers of all lands unite, you have nothing to lose but your chains."

There is a world to win. A world freed from poverty, disease, hunger, illiteracy and despair. A world where the true potential of humanity is released and can flourish. That is the greatest end to which anyone can aspire, the only cause worthy of giving one's life for. Karl Marx gave his whole life to this cause, sacrificing everything for the cause of the emancipation of the working class.

Whilst those who have written to bury Marxism over the last 150 years have vanished into obscurity the ideas of Marxism not only retain their relevance but are now gaining a new audience. In general in the hands of bourgeois academics the ideas of Marxism will be transformed and vulgarised into dead dogma. In the hands of the workers movement, inscribed on the banner of the youth, they will serve their true purpose. As Marx himself explained that purpose is to help not only to understand the world, but to change it.