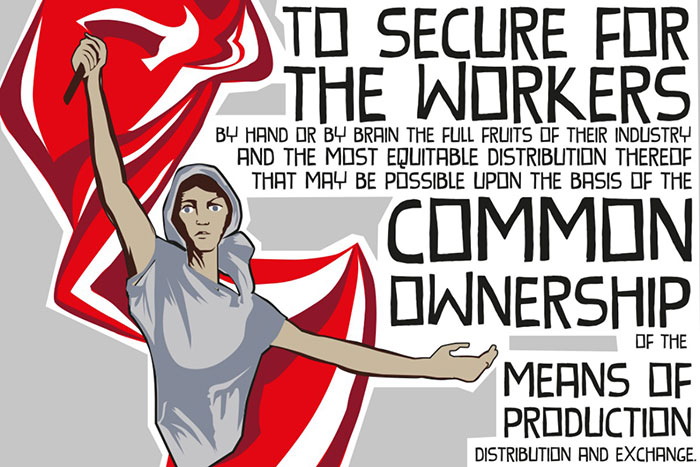

British Labour movement

Ever since the formation of the Labour Party in 1900, there has been controversy on the left over whether or not to participate in the party. To develop a correct understanding of this question, it is important to look at the experience of the past. Our task is to learn from history in order to avoid unnecessary mistakes. History, after all, is littered with the wreckage of small sectarian groups who attempted to mould the workers’ movement into its preconceived plans and failed.

Ever since the formation of the Labour Party in 1900, there has been controversy on the left over whether or not to participate in the party. To develop a correct understanding of this question, it is important to look at the experience of the past. Our task is to learn from history in order to avoid unnecessary mistakes. History, after all, is littered with the wreckage of small sectarian groups who attempted to mould the workers’ movement into its preconceived plans and failed.

Different “Marxist” groups have made one mistake after another on this key question. Towards the end of the 1960s, a number of left groups abandoned work in the Labour Party in disgust at the counter-reforms of the then Labour government. They wrote off the party and set about building their own independent revolutionary parties, ignoring everything that had been written on the importance of the mass organisations. The more isolated they were, the more ultra-left they became. Rather than connect with the real movement, they continually sought to tear the advanced workers away from the mass. They saw their prime task as to “expose” the leadership through shrill denunciation. This has been the hallmark of all these different sectarian groups. With such antics they end up playing into the hands and reinforcing the position of the right-wing leaders.

— From Britain: Marxism and the Labour Party – Some important lessons for today