In drawing up a balance sheet of 1918, the first and most important point is that, against all the odds, the Russian Revolution of October 1917 survived. Lenin held a small celebration when the revolution outlasted the three months or so of the Paris Commune. He had thought the survival of the revolution would be touch and go, as it was. But in early February 1918, when the Paris Commune milestone was passed, the forces of reaction were still gathering.

Part one | part two | part three | part four | part five

“Three or four Japanese or American divisions are enough to put an end to the Bolsheviks.” From a telegram sent by the US Ambassador in France, January 1918.

“This year will see the end of Bolshevism.” From a speech by Marshal Foch, France, February 1919.

The initial efforts within Russia by the old defeated classes to mount a counter-revolution had been decisively defeated in Petrograd and Moscow and were being overcome throughout Russia, especially in all the towns and cities. But the international capitalist class, temporarily held back by the First World War, understood the danger Bolshevism represented and after initially hoping to tame it and bend it to its will had, by the spring of 1918, embarked upon an increasingly determined policy of seeking the military overthrow of the new regime.

Initially, they armed and supplied the various ragtag and bobtail forces that represented opposition to the Bolsheviks. They weren’t particularly fussy about who got support. At one stage it might be the SRs, another the Mensheviks and eventually, more and more, the vicious reactionary generals and admirals of the old Imperial Army and Navy and their White armies. Once the fate of the First World War was known they began a more direct intervention, sending troops, ships and arms to various footholds in the peripheral areas of the north, south and east of the vast country; and even some detachments deep into Russia itself. But the emerging power of the new society, resting on the labouring and previously exploited peoples, proved too much for imperialism. By December 1918, although still beleaguered, Soviet Russia stood firm and ready to roll back the combined forces of national and international reaction.

The positive impact of revolution

The positive impact of the revolution was perhaps most apparent in giving the previously downtrodden a sense of their own worth as full and complete citizens. The raising of the status of the proletarian and the poor peasant from the bottom to the top not only created a different ethos and set of values in society it also began the process of releasing whole new layers of energy, talent and creativity. Of course, given the immediate harsh circumstances in which the revolution was born and the still harsher environment under civil war conditions that followed, the material benefits of the revolution took many years to bear fruit. But the mental slavery – of being regarded as virtually worthless, as mere serfs and wage slaves under the yoke of those who called themselves masters and lords – was broken. The development of soviet democracy, involving – for the first time – many hundreds of thousands of people in direct and (for periods), daily participation in decision making and charting outcomes, was a remarkable change for the masses.

The immediate actions of the new government in nationalising land and thereby ending the large rural estates of the aristocracy and other large landowners received a very positive response from peasants of all classes, but especially those with little or no land. It also unleashed a class struggle in the countryside between rich and poor peasants for the control of land and other resources. The Bolsheviks’ support for the poor peasants was a vital factor in securing the revolution. By the same token, the early nationalisation of the banks and some industries, along with workers’ control in the workplace, immediately raised confidence among the urban masses that their government was really on their side and fulfilled its promises. These tremendous gains for the working class help to explain the heroic sacrifices they were to make in defending the revolution, which they took ownership of and protected.

Although resources were scarce, the new state allocated these in fair and just ways. No longer did the rich take the lion’s share and leave crumbs for the rest. As the new July Constitution stated, the government’s motto was, “he shall not eat who does not work”. Although not enshrined in law and not meant to be taken literally for every age group, it provided a new spirit and intention to govern equally.

Whilst it was not possible to shrug off centuries of prejudices and inculcated attitudes overnight, immediate decrees by the Soviet regime began the process of social change. New laws, ending legal discrimination against women, gays and minority groups were groundbreaking and had an immediate impact. Equality and ease of divorce for both men and women was an important step in the liberation of women. Similarly, equality of all children born in or out of wedlock was a revolutionary step in 1917. In November 1918, Russia held its first All-Russia Congress of Working Women and Lenin gave the opening speech, in which he said:

“For the first time in history, our law has removed everything that denied women rights. But the important thing is not the law. In the cities and industrial areas this law on complete freedom of marriage is doing all right, but in the countryside it all too frequently remains a dead letter. There the religious marriage still predominates. This is due to the influence of the priests, an evil that is harder to combat than the old legislation.”

Although the arts in Russia had possessed a vibrant avant-garde before the revolution, the upheaval of 1917 gave a massive spur to new thinking and creativity / Image: Flickr, cea

Although the arts in Russia had possessed a vibrant avant-garde before the revolution, the upheaval of 1917 gave a massive spur to new thinking and creativity / Image: Flickr, cea

In this, Lenin pointed to the issue of religion; and the fact that another, early decree of the Soviet Government had been to end the entrenched position of the Russian Orthodox Church in all aspects of the state. The massive landholdings of the church had been confiscated, many of its rights and privileges ended and, although religion was not banned, it no longer held the masses in the same thrall. As Lenin said, this proved much harder to break in the countryside than the towns.

Although the arts in Russia had possessed a vibrant avant-garde before the revolution, the upheaval of 1917 gave a massive spur to new thinking and creativity. In all areas – music, literature, art, poetry and architecture – the massive changes produced shockwaves in the creative world. One of the new factors that the state and artists grappled with was how to place art at the service of working men and women, reflecting their struggles and their needs. Poster art flourished, new vibrant designs of cloth and materials also took place and agitation and propaganda became linked to the theatre in ‘agitprop’ productions. New art education was also established under avant-garde artists and architects.

The negative impact of counter-revolution and civil war

Although Soviet Russia overcame all the various crises in 1918, this success came at a price. This price was felt in all spheres: economic, social and political. In economic terms, the continued efforts to overthrow and destabilise the new Soviet government meant that the economy, already in long-term decline in any event, continued to suffer from dislocation and disruption at all levels. The disastrous Brest-Litovsk Treaty, necessary as it was, added to the economic woes by depriving the new state of vital resources. The action of Allied powers to fund and support armed opposition meant that the needs of war continued to affect production and the use of resources.

The opposition, at vital moments, of Menshevik-led railway workers meant that the distribution systems were adversely affected, particularly in the first half of 1918. The curtailing of capitalist market relations in terms of food and goods led to an acute crisis in providing sufficient food for the urban population. The rich peasants – the kulaks – refused to supply grain and other food on the terms demanded by the government and forceful methods to extract food from the countryside had to be deployed. The suffering in the cities was considerable and only harsh rationing enabled the urban populations, albeit reduced in numbers, to survive. The economic blockade instituted by the imperial Allies also limited the ability of the government to export and import.

The Bolsheviks’ original plan to have some kind of transition between an outright capitalist economy and an outright socialist, planned economy had to be largely scrapped during the course of 1918 as it became clear that only a more rapid and complete transformation, placing most of the levers of power in the hands of the government, would ensure victory in these hard times. Thus, “war communism” was born and remained in place until more peaceful conditions allowed for a modified transition from one system to another. In the conditions of 1918, it proved essential to deploy, in the service of the state, specialists and professionals who carried the values and aspirations of the old system. Thus, industrial managers, administrative professionals and skilled army leaders and operators were used to assist the fledgling workers’ state overcome early deficiencies in these areas.

The growing civil war dominated life in the latter part of 1918 and over the following three years. In those areas directly affected, the impact was considerable. Many were caught up in the battles and died; others suffered great hardship and struggled to survive. In order to fight the Whites, the flower of the proletariat was drawn into the new Red Army. By the end of 1918, the Red Army was over 500,000 strong and would double again in 1919. Not only did this mean that the youngest, most energetic and most class-conscious workers were taken out of their communities and factories, but it meant many were killed or injured. The long-term impact of this on the future course of the revolution was considerable and played an important part in the eventual usurpation of power by the party bureaucracy led by Stalin. In immediate terms, it affected industrial production and the development of administrative system.

The need to combat efforts by class and political opposition to sabotage, undermine and overthrow the new soviet system led to a growth of a new state security apparatus. The Cheka began as a fairly low-key poweration and dealt relatively leniently with opposition politicians. But, as the intensity of the onslaught from all sides increased, so the Cheka expanded and its methods became more forceful. In other words, White Terror was met by a degree of Red Terror. Once dealt with, the level of repression and harshness abated. But the size and reach the Cheka had increased considerably; and developed its own layers of bureaucracy and a degree of independence that, under the control of Stalin, was deployed against Bolsheviks.

The response of the international labour movements to the revolution

The Bolshevik-led revolution in 1917 had a major impact on all socialist parties in every part of the world. But it took time to see the full effect, as the revolutionary movements were very small in most countries. In Germany, where a crisis had been brought on by their defeat in the First World War and the acute economic problems the country faced, there was a revolutionary wave, and the Spartacus League grew rapidly. But the great weight of the Social Democratic Party (SPD), so long established in the trade unions and in the working class generally, proved too powerful to overcome. The SPD played a treacherous role in placing themselves at the head of the rising, militant working class, cynically supporting the new workers and soldiers’ councils and then deploying reactionary troops to cover the tide of revolution in blood. These actions can be seen as one of the roots of fascism in Germany.

In Britain, the Labour leaders similarly sought to control a rising tide of militancy and also proclaimed themselves in support of workers and soldiers’ councils and then stalled until the mood lessened. The centre of revolutionary action in Britain was undoubtedly Scotland and especially the Clyde area. But again, the revolutionary parties were small, albeit influential, and failed to take the struggle beyond industrial militancy. The best leader by far was John McLean, appointed by the Bolsheviks as one of their British Consuls. But he was specifically targeted by the state and imprisoned several times, making his political contributions less impactful.

In France, although the mood of soldiers grew rebellious in 1917 and there were many mutinies, there was not a strong revolutionary party to offer a lead. Jaures, one of the most promising leaders, had been assassinated in 1914. Within the Socialist Party, the left were heavily defeated after the war and eventually departed to form the kernel of the French Communist Party.

In the USA, whilst the revolution had an impact on the most class-conscious workers, the main left-wing party (the Socialist Party) was dominated by reformists and the left elements were scattered and weak. The revolution helped to strengthen the genuine left and there was a rise in working-class militancy after the end of the First World War, but the state and the main trade union movement easily contained it.

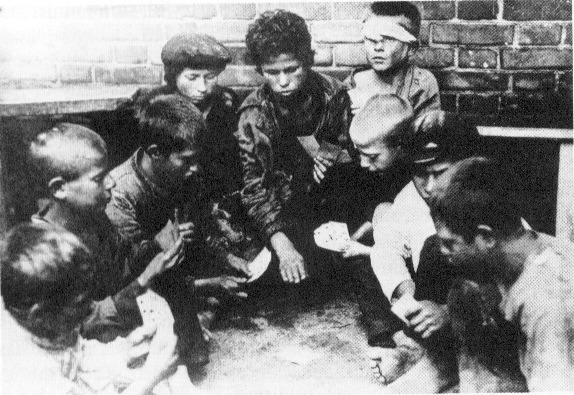

The revolution's survival through the harsh days of 1918 allowed the hope it inspired to flourish and continues to resonate to this day / Image: public domain

The revolution's survival through the harsh days of 1918 allowed the hope it inspired to flourish and continues to resonate to this day / Image: public domain

This is the immediate picture from the standpoint of the situation at the end of the first year of the revolution. In the longer-term, the impact was vast. The formation of the Third Communist International in early 1919 helped to shape the emerging post-war political scene across the globe.

The overthrow of the system of capitalist and landlord rule in Russia was like an earthquake that rumbled and shook the world for decades to come. The example inspired the Chinese Revolution and gave hope to millions of workers worldwide. Its survival through the harsh days of 1918 allowed this hope to flourish and continues to resonate to this day.